The Big Combo, directed by Joseph H. Lewis and photographed by John Alton, stands as a distilled example of the film noir movie aesthetic — a compact, brutal, and meticulously staged tale of obsession, corruption, and the moral cost of pursuing justice. Produced in 1955 with a modest budget and a spare running time, it achieved a critical reputation that has only grown with restorations and retrospectives. Drawing on production facts, plot details, and the film’s own dialogue and set pieces, this analysis examines why The Big Combo remains a touchstone for students and lovers of the film noir movie.

Outline

- Introduction: The film’s place in noir history and an overview of its central conflict

- Production context and key credits

- Plot overview: a concise narrative walkthrough

- Character study: Leonard Diamond, Mr. Brown, Susan Lowell, and the gang

- Recurring motifs and themes: obsession, power, betrayal, and identity

- Cinematography, sound, and design: John Alton and David Raksin’s contributions

- Pivotal scenes analyzed: interrogation, Bettini confession, lie detector, torture, the private vault, and the final hangar showdown

- Performances and casting: why the actors matter

- Legacy, restoration, and the film’s endurance in the film noir movie canon

- Conclusion: The Big Combo as a moral and aesthetic exemplar

Introduction: Where The Big Combo Sits in Noir

The Big Combo opens as a compact case study in noir’s recurrent preoccupations: the blurred line between lawful authority and personal vendetta; the seductive, destructive hold of organized crime; and a bleak vision of urban life where violence is transactional and human beings are expendable. The central thrust of the film noir movie is embodied in one relentless, driven protagonist — Police Lieutenant Leonard Diamond — whose crusade to break a criminal syndicate becomes indistinguishable from a private obsession. From the outset the film stakes its claim as both procedural and parable, driven by dialogue as sharp as a scalpel and images as stark as a winter street.

Even in its most concise beats, the film noir movie sensibility is clear: there is no comfortable moral center, each verdict is costly, and the camera delights in revealing the architecture of power that enables crime. The Big Combo condenses these ideas into 88 minutes of striking visuals, terse character exchanges, and set pieces designed to unsettle as much as they illuminate. This review focuses on how the film achieves its effect through performance, cinematography, narrative design, and tonal control.

Production Context and Key Credits

The Big Combo was released in 1955 and is credited to director Joseph H. Lewis, writer Philip Yordan, and cinematographer John Alton. Cornel Wilde stars as Lieutenant Leonard Diamond, with Richard Conte as the chillingly composed gangster Mr. Brown and Brian Donlevy as Joe McClure, Brown’s second-in-command. Jean Wallace — who was Cornel Wilde’s wife at the time — plays Susan Lowell. The music was composed by David Raksin.

Produced by Security Pictures and Theodora Productions, the film was shot in black and white on a relatively small budget (documented at approximately $500,000) and completed efficiently in a brief production schedule of 26 days. The economy of production contributed to the film’s concentrated intensity; there is no excess, no filler, only carefully chosen scenes pushed to their cinematic extremes.

John Alton’s involvement is especially noteworthy. As cinematographer, he brought a signature chiaroscuro style to the project — deep, smoking blacks, saturated shadows, and brilliantly placed highlights that turn common objects into portentous threats. Alton’s compositions would provide the visual grammar for the film noir movie aspects of The Big Combo: motifs of confinement, entrapment, and moral ambiguity rendered visually.

Plot Overview: Compact, Coiled, and Cruel

The narrative begins with Police Lieutenant Leonard Diamond obsessed with bringing down the gangster Mr. Brown and his organization. Brown is not merely a criminal; he is a carefully cultivated persona, a businessman of vice whose operations touch multiple cities and whose hands stay clean — “He’s clean. He got nothing on him, not even the parking.” Diamond’s case is less about a single homicide than it is about collapsing a system of protection and corruption that funnels violence into the lives of ordinary people.

Diamond’s pursuit is both professional and personal: he courts the testimony of Susan Lowell, Mr. Brown’s girl and a woman trapped in his orbit. Susan is despondent, suicidal at one point, and appears to be both victim and enabler in the moral ecology of the syndicate. Diamond’s obsession with her is an undercurrent running beneath the official investigation; he wants Brown’s downfall, but he also wants Susan rescued.

As Diamond gathers leads, he uncovers references to a woman named Alicia, who becomes a crucial, mysterious figure. The ex-crewman Bettini suggests Alicia may have been murdered on a voyage years earlier, tied to an anchor and dropped into the ocean. Other leads — a skipper named Dreyer, the bankrolled antique shop, and a set of unnamed henchmen — form a network of half-truths that Diamond must tenderly pry open to reach the core of Brown’s operation.

The film unfolds in a series of confrontations: Diamond’s aggressive interrogation tactics, Brown’s retaliatory torture of the lieutenant, the internecine betrayals among Brown’s crew, and finally a climactic foggy hangar showdown in which the film’s noir aesthetics converge with its moral reckoning. The final image — silhouettes in fog — closes a narrative that values atmosphere and inevitability over clean resolution.

Character Study: The Obsession and the Organization

Lieutenant Leonard Diamond

Leonard Diamond is not a procedural hero in the comfortable sense. He is a man consumed by the chase. The film noir movie archetype of the obsessive investigator fits Diamond: a cop whose sense of justice verges on personal vendetta. He spends eighteen thousand six hundred dollars of precinct funds chasing Brown and his leads — a fact that brings him into conflict with his captain, who recognizes the political and financial impossibility of Diamond’s obsession. Yet Diamond persists.

Diamond’s methods are unorthodox and sometimes brutal; he pushes suspects, pressures witnesses, and risks outright physical harm to himself. The transcript reveals scenes where Diamond’s interrogation becomes an ethical quagmire: he is the law, but he also violates procedural norms to collect evidence. His love for Susan Lowell — or his desire to rescue her — blurs the line between professional motive and personal compulsion. That complexity is central to the film noir movie portrayal of a hero who is as morally compromised as the villains he pursues.

Mr. Brown

Mr. Brown is the film’s most memorable personification of controlled menace. He is not a larger-than-life mob boss dictating orders in a roar; he is a personality exercised through tone, social grace, and a coldly articulated philosophy of power. Brown’s famous line about hate — “Hate the man who tries to beat you. Kill him, Benny. Kill him.” — demonstrates a warped pedagogy of violence: the promise of reward through hate, the notion that brutality is an instrument of success and sexual allure.

Brown’s organization operates like a machine. He eliminates competitors and inconvenient witnesses, blackmails and buys his way out of direct culpability, and wields the raw economics of influence. When asked who runs the world, he knows how to answer, and he understands the currency of instilling fear. The film noir movie dynamic is in full effect: Brown is not merely a criminal, he is a social force that manipulates institutions.

Susan Lowell and Alicia

Susan Lowell represents the classic noir woman who is both victim and enabler. She is Mr. Brown’s girl — “Brown’s girl” — and her entanglement appears at once sincere and strategic. Despondent, suicidal, and fearful, Susan oscillates between wanting to be saved and accepting her role. She is the cleavage in which the film pries its way into Brown’s private life.

Alicia functions as a ghostly presence: an off-screen puzzle whose identity and fate set the investigative arc in motion. Initially an enigma, Alicia is suggested to be Brown’s former wife betrayed and possibly murdered. Her existence — whether alive, dead, or both in rumor — catalyzes fear inside Brown’s enterprise and becomes the hinge on which confessions rotate.

The Henchmen and Secondary Players

Joe McClure, Fante, Mingo, and the secondary players (Dreyer, Bettini, Rita, Sam) populate the world of The Big Combo like gears in a continuingly grinding machine. They are subject to Brown’s authority, tempted by self-advancement, and ultimately disposable. McClure’s ambition and Mingo’s loyalty unravel as the plot demands. Bettini and Dreyer are links to the past; they offer testimony and then, inevitably in this film noir movie, are silenced.

Recurring Motifs and Themes

The Big Combo is thematically dense. It explores the cost of obsession, the corrosive effects of centralized criminal power, and the moral slipperiness of those who claim the right to enforce justice. Several motifs recur:

- Obsession as moral compromise: Diamond’s fixation becomes an instrument that warps his ethical judgment. The film noir movie often features a protagonist whose pursuit flattens nuance and invites ruin.

- Power’s sanitization: Brown’s outward civility hides a cruelty that the film renders visually — the cleaned public spaces versus the bloodied private ones, the hotel versus the river.

- Disposability of human life: The henchmen and victims show how quickly lives can be bought, silenced, or destroyed.

- Identity and false narratives: Alicia’s ambiguous existence and the falsified or burned records (the missing ship’s log) underscore how stories are fabricated to protect power.

- Visual motifs: fog, shadows, closeups of hands and money, the private vault — all of these deliver visual metaphors for secrecy and moral concealment.

These themes are classic to the film noir movie but The Big Combo renders them with particular starkness through image and scripting. The result is a film that feels relentless: there are no easy moral outs, only consequences.

Cinematography, Sound, and Design

John Alton’s photography is the film’s most explicit declaration of intent. Alton uses high contrast, deep blacks, and bold framing to compress the film’s world into a series of visual observations that read like legal evidence and poetic indictment at the same time. The lie detector scene, the lit cigarette in a dark hotel lobby, reflections in puddles — all are compositional choices that turn mundane objects into moral signifiers.

David Raksin’s music is spare, and the film intentionally moderates orchestral sweep to let image and silence do much of the heavy lifting. The absence of an overly lush score in key scenes enhances the film noir movie’s sense of existential dread: sound is often ragged — breaths, rain, diesel trucks — rather than cinematic decor. This sounds small on paper but amplifies the sense of realistic menace on the screen.

Production design is similarly economy-driven. Settings are functional and suggestive. Whether it is the antiseptic hospital ward where Susan mumbles “I feel so cold,” the cramped antique shop, or the final foggy hangar, each location is tailored to the dramatic beat it supports. The vault sequence — “This is my bank” — literalizes Brown’s industry of vice and temptation. The film noir movie loves such objects: a vault, a ledger, an anchor — each becomes evidence and symbol.

Pivotal Scenes Analyzed

The Hospital Interrogation

One of the film’s first emotional hooks is the hospital interrogation of Susan. She is fragile, repeatedly asking to sleep, and yet she offers an image of Alicia’s name scribbled on the fog of a window: “He was writing a name on it… Alicia.” The line is simple and haunting. Susan’s inability to remember, coupled with the image of the misted window, functions as a noir code: memory is partial, the truth smudged, and men who are experts at erasure — like Brown — can rub it out.

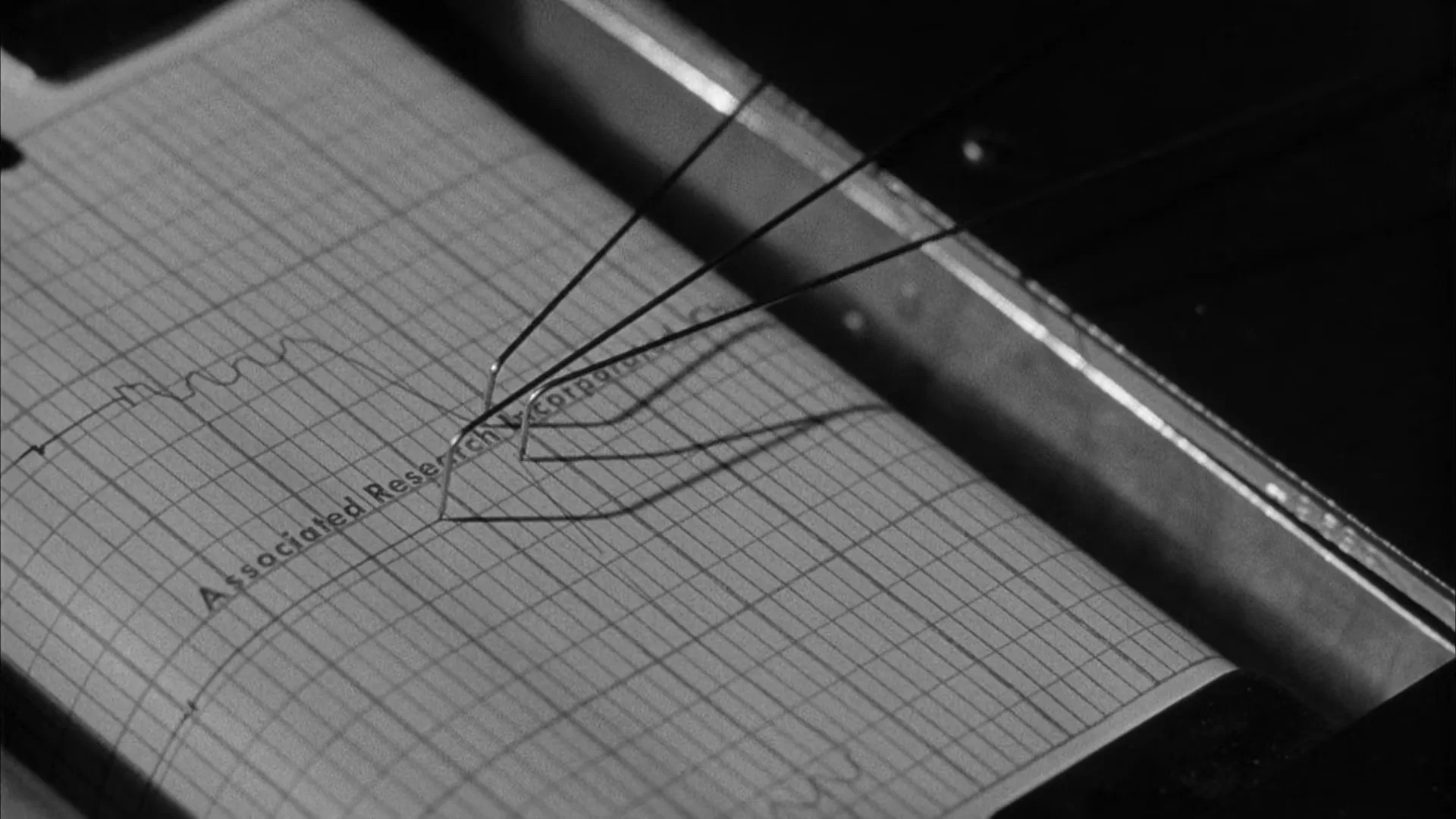

The Lie Detector

The lie detector scene is a masterclass in how the film noir movie translates psychological pressure into cinematic spectacle. When Mr. Brown hears the name “Alicia,” a physiological betrayal occurs; the machine measures a rise that the man’s words cannot account for. Diamond’s observation — “When you heard Alicia, your heart went bang. You don’t lie with your blood pressure” — is the film’s forensic logic. The lie detector doesn’t convict Brown; it makes him reveal a fissure in his composed façade. The moment crystallizes the film noir movie’s fascination with the body as witness.

Bettini’s Confession and the Anchor Theory

Bettini, a rough-handed seaman who once ferried Grazi and Brown, tells a story of Alicia’s drunkenness, a spat, a thrown wedding ring, and then sudden disappearance. Bettini suggests an anchor was purchased at the Azores and implies that Alicia may have been tied to it and dropped overboard. The scene is crucial because it reframes the film’s core mystery: was Alicia murdered? Or was another crime committed entirely? Bettini’s testimony is partial, colored by fear and memory deterioration — yet the image of the anchor becomes an emblem for what criminal power does to truth: anchors the past irretrievably in the deep.

Torture and the Hair Tonic Scene

Brown retaliates in a way that is physically and morally defiling: he orders his men to pour a bottle of hair tonic down Diamond’s throat, a humiliating assault that is equal parts revenge and demonstration. The scene is a reminder that in the film noir movie world, power is performative. The assault is not meant to kill Diamond; rather it is meant to humiliate, to show Diamond how expendable he is. Yet the attack backfires because it reveals Brown’s willingness to cross moral thresholds, making him more vulnerable to legal and moral condemnation.

The Private Vault

Inside Brown’s private vault, money and guns are catalogued as assets. Brown’s statement — “We don’t take checks. We deal strictly in cash” — is an explicit declaration of the organization’s untouchable finances. Susan’s access and the photograph of Alicia that she shows Diamond become narrative leverage. The vault is a mise-en-scène for the criminal economy: safes, stacks of bills, and the private ledger of a man who trades in people’s lives as easily as currency.

Final Hangar Showdown

The final set piece transposes noir into mythic space: a fog-shrouded hangar where visibility is reduced and silhouettes dominate. The fog lamp becomes a weapon of revelation; Susan flashes the light into Brown’s eyes, temporarily blinding him and permitting Diamond to effect an arrest. The film ends with silhouettes in fog — a noir image of unresolved, shadowy moral victory. The hangar is a stadium of ambiguity: is the arrest justice or merely temporary containment? The film noir movie rarely supplies tidy resolutions, and The Big Combo leaves its moral reckoning in silhouettes and muffled gunfire.

Performances and Casting

Cornel Wilde’s Leonard Diamond is not an invulnerable hero; he is dogged, prickly, and stubbornly honest in ways that alienate colleagues but secure purpose. Wilde’s performance captures the desperation of a man who has converted law into crusade. Richard Conte’s Mr. Brown is terrifying in quietness: he is measured, articulate, and ideologically committed to violence as power. Conte’s voice and stillness make Brown’s cruelty almost more potent than a blustering gangster.

Brian Donlevy’s Joe McClure is the classic jealous lieutenant: ambitious, resentful, and ultimately disposable. Jean Wallace as Susan Lowell conveys fragility and conflicted loyalty. Secondary performances — Ted de Corsia as Bettini, John Hoyt as Dreyer, and Helen Walker in her last screen role as Alicia — add texture. The ensemble functions like a theatre troupe: each actor understands how to create an atmosphere of dread while contributing to the film’s investigative logic.

Script and Dialogue: Economy with Edge

Philip Yordan’s screenplay is sharp and economical. The dialogue does heavy lifting without being ostentatious. Lines such as “First is first and second is nobody” and the exchange about the treasurer who can “pick up a phone and call Chicago and New Orleans” provide world-building in a few sentences. Yordan’s script leaves space for Alton’s camera to interpret and for actors to embody. The result is a film noir movie that functions as equal parts crime procedural and psychological study.

Legacy and Restoration

The Big Combo has enjoyed renewed appreciation through preservation efforts and home media restorations. In 2013, Olive Films released a Blu-ray with a restoration completed by UCLA Film & Television Archive and the Film Foundation. A newer HD restoration followed in 2018 by Arrow Films in the UK. These restorations bone out the details: Alton’s blacks register with greater nuance, the fog sequence becomes more atmospheric, and Raksin’s score is balanced to let silence breathe. The film’s survival in the noir canon is bolstered by such efforts.

It is worth noting that legal formalities left the film in public domain territory after a copyright notice was rejected in 2007, which affected its distribution and access. Nevertheless, critical esteem and curatorial attention — notably programming on classic cinema showcases — have ensured its continued availability for study and appreciation.

The Big Combo as a Study in Noir Mechanics

As a specimen of the film noir movie, The Big Combo demonstrates how narrative compression can produce thematic density. The film’s brisk runtime forces every scene to function as evidence: an interrogation, a lie detector result, a confession, a murder, a betrayal. There is no excess. The movie is relentless, and that relentlessness is moral as well as cinematic. The world of the film is one of containment: money in vaults, secrets in chests, people in cycles of fear. The camera becomes an investigator and the audience an observer of consequences.

One might argue that the film’s moral complexity is its lasting strength: justice is achieved only partially, and the cost of pursuit is measured in lost lives and compromised ethics. Diamond may succeed in arresting Brown, but the path to victory is littered with casualties — Donna Drew’s Miss Hartleby, Rita Gould’s Rita, and the many unnamed victims whose lives intersected with Brown’s merciless logic. The film noir movie trusts the viewer to judge beyond the final arrest and to contemplate what remains of order when law is practiced as obsession.

Why The Big Combo Still Matters to Noir Study

Film scholars and classic cinema enthusiasts return to The Big Combo for several reasons:

- Visual Style: John Alton’s cinematography remains an essential case study for anyone exploring lighting, framing, and the symbolic use of shadow in noir.

- Moral Ambiguity: The film refuses to offer a heroic narrative unblemished by compromise. Instead, it presents a realistic — and therefore unsettling — portrait of how justice functions when the system is as compromised as the criminal enterprise it confronts.

- Structural Economy: In 88 minutes, the film constructs a complete universe: past crimes, buried secrets, interpersonal rivalries, and a final, foggy resolution.

- Performance Ensemble: Conte’s measured cruelty and Wilde’s doggedness provide a study in how actors can convey institutional and personal intensity within the film noir movie idiom.

- Curatorial Importance: Restorations and festival screenings have positioned the film as indispensable viewing for anyone serious about noir.

Concluding Assessment: A Compact Classic

The Big Combo is both a procedural and a morality play: a film noir movie that operates with the ruthless efficiency of the very crimes it depicts. Joseph H. Lewis’s direction, John Alton’s cinematography, Philip Yordan’s script, and the cast’s tight performances cohere into an experience that is as intellectually crisp as it is emotionally corrosive. The movie demands attention not only for its story but for the way it stages forensic moral questions: how far should those who enforce law go to bring powerful criminals to account? At what cost? And can justice be satisfied when the structures that uphold it are themselves vulnerable to corruption?

For cinephiles and students of classic cinema, The Big Combo remains a mandatory entry in the film noir movie canon. Its spare production, haunting imagery, and uncompromising moral vision make it a work that rewards repeated viewings and careful study. Those interested in the period’s aesthetics should seek out modern restorations to experience the film as it was meant to be seen: sharp, shadowed, and uncompromising.

Recommendations for Viewers and Students of Noir

The critic recommends the following approach when engaging with The Big Combo:

- Watch the film in a restored transfer when possible to appreciate John Alton’s palette; the play of deep black and highlighted faces is essential to the film noir movie experience.

- Pay attention to the dialogue economy: many lines function as both characterization and exposition, particularly those delivered by Mr. Brown and Leonard Diamond.

- Study the supporting characters (Bettini, Dreyer, Rita) as necessary connective tissue; their fates reveal the wider social costs of organized vice.

- Observe recurring visual motifs (mirrors, misted windows, the vault) and consider how they operate symbolically to manifest secrecy and entrapment.

- Rewatch the lie detector and hangar sequences to examine how sound design, camera movement, and editing establish suspense without melodrama.

Final Notes on Preservation and Access

Restoration work has restored The Big Combo’s luster for modern audiences, and archival releases allow scholars to examine the film in ways that bootlegs or degraded prints could not. The film’s presence in the public domain complicated its distribution history, but curatorial efforts and formal restorations have ensured that the film remains visible and influential.

Ultimately, this film noir movie continues to offer a hard lesson: that the pursuit of power and the pursuit of justice can mirror one another in their capacity for destruction. Anyone exploring the depths of noir owes themselves the experience of sitting with The Big Combo, watching the vertically lit faces and listening to the brittle dialogue as the moral world tightens like a noose around both the righteous and the corrupt. It is a cold, intelligent film — and it remains an essential specimen for understanding what noir does and why it endures.

Suggested further reading and viewing:

- Compare The Big Combo’s visuals with other John Alton collaborations to appreciate the cinematographer’s stylistic consistency across the film noir movie field.

- Contrast Joseph H. Lewis’s direction here with his earlier and later works to chart how he handles pacing and tension.

- Study contemporary reviews and modern restorations to understand how reception of the film evolved over time, particularly in the context of noir revival programming.

The Big Combo is not merely a film to be watched; it is a film to be interrogated. As a film noir movie, it probes, exposes, and refuses to console. It remains a compelling invitation for anyone who wants to understand how mid-century cinema dramatized the collision between law and the economic architecture of crime.