Beat the Devil, the 1953 picture directed by John Huston, sits at an odd angle in the history of classic cinema: part caper, part satire and wrapped in the garb of what one might call a film noir movie with a wink. This review draws on the film itself and its documented record to reassess how Huston, working from a day-to-day screenplay co-written with Truman Capote and adapted from Claud Cockburn’s novel, used noirish materials—crooked businessmen, moral ambiguity, dark humor—to make something intentionally off-kilter. As a classic cinema critic examining Beat the Devil both as artifact and argument, the article places the film into context, traces its plot beats and characters, considers production anecdotes that shaped the result, and weighs its reputation as an early example of a film noir movie deployed as spoof and experiment.

Outline: What This Examination Covers

- Historical and industrial context for Beat the Devil

- Detailed plot summary and how the narrative retools genre expectations

- Character-by-character analysis and principal performances

- Visual and tonal elements that connect the film to a film noir movie lineage

- Production stories that influenced the film’s texture and sound

- Contemporary reception, later reassessments and the 2016 restoration

- Final arguments on why Beat the Devil should be considered (or resisted as) a film noir movie and what modern audiences might take from it

Introduction: Huston, Capote and a Mischievous Premise

John Huston took a risky stance when he announced that Beat the Devil would be less a straight adventure than a deliberate, loose parody of the sort of shadows he had previously worked with in films like The Maltese Falcon. The screenplay partnership with Truman Capote is one of those unusual pairings—Huston’s hard-nosed worldliness joined to Capote’s ear for idiosyncratic dialogue—that produced an uneven, provocative picture. That uneasy blend is part of the reason Beat the Devil still provokes debate among those trying to categorize it as a film noir movie, a caper, a comedy, or a camp precursor.

The film’s premise is tidy and mischievous: a group of petty crooks and opportunists hatch a plan to acquire uranium-rich land in British East Africa. Huston and Capote transform that premise into a needle-sharp lampoon of greed, colonial opportunism and the hypocrisy of “respectable” men who consort with bandits to get what they want. Thematically, the film centers on duplicity—who lies, who is lying to themselves, and which schemes actually work. These are the familiar preoccupations of noir tales, yet Huston pushes them toward comic absurdity. The result is a work that defies neat classification: at once an example of a film noir movie sensibility and an explicit undermining of noir’s seriousness.

Historical Context: Postwar Anxiety, Uranium and Genre Play

Beat the Devil emerged in the early 1950s, a moment when wartime dislocations had given way to Cold War anxieties and a booming but anxious film industry. The plot’s MacGuffin—uranium—was newly charged in the public imagination. That element, indispensable to atomic energy and to geopolitical leverage, injected urgency into the film’s otherwise puckish tone. The characters’ scrambling for mineral wealth foregrounds a postwar scramble: not just for land, but for power and survival.

Within film history, the postwar period is also where noir tropes matured: disillusioned protagonists, crooked offers, morally compromised institutions and glowering urban or international locations. Huston’s film takes those motifs and relocates them to a sunlit Mediterranean port and an African shoreline, displacing noir’s usual urban claustrophobia into open air—which is precisely part of the spoof. Yet the moral murk stays in place. That is why Beat the Devil operates as a kind of experiment: it borrows the vocabulary of a film noir movie but reassigns the grammar. The shadow is still there; Huston wants audiences to see it and laugh at it too.

Plot Summary: A Crooked Map of Greed and Mistakes

The film opens with four conspirators and their reluctant associate, Billy Dannreuther, planning to traffic in uranium deposits in British East Africa. The band consists of Peterson, Julius O’Hara, Major Jack Ross and Ravello, men who are as scheming as they are comically inept. Billy, a one-time wealthy American reduced to managing the gang’s affairs, is pulled between avarice and conscience. Over the course of the picture, the conspiracy unspools in comic misadventure: misunderstandings, sexual flirtations, a car that goes over a cliff, a dispatch box gone astray, a drunken captain, attempts at murder, a ship’s breakdown, a landing on an African beach and an eventual Scotland Yard intervention that collapses the crooks’ plan.

But the skeletal beat-list understates Huston’s pleasure in diversions: the film continually interrupts its own tension with digressions—a flirtation between Billy and Mrs. Gwendolen Chelm, Maria Dannreuther’s coquettish maneuvers, and an ensemble of deceivers whose scheming combusts into in-fighting. The gang’s obsession with the “time factor”—the fear that delay will expose them—drives many of their worst decisions. That sense of time as a criminal’s enemy is a classic noir concern; Huston parodies it by making the gang’s anxieties produce absurd outcomes.

Key Episodes

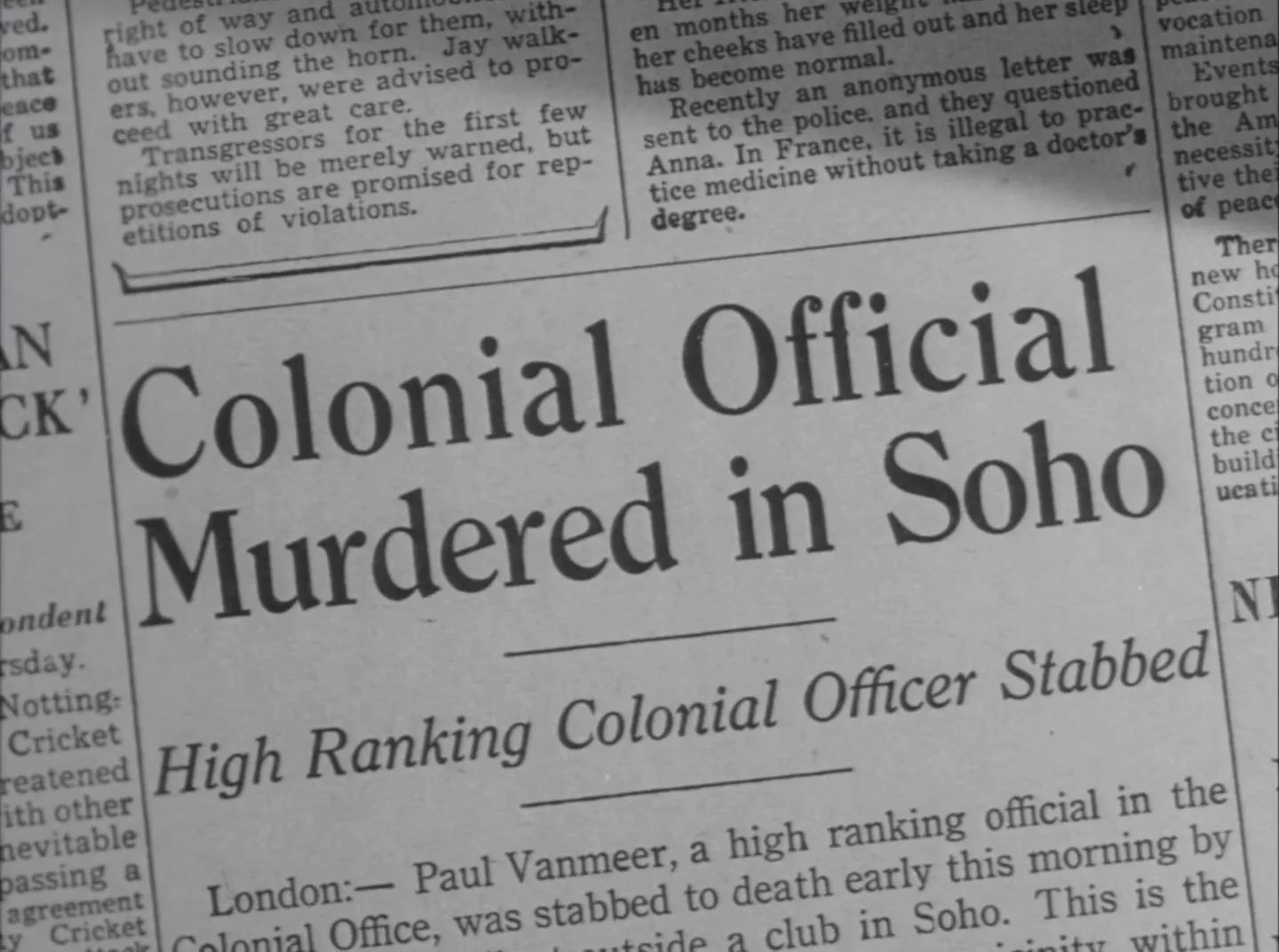

- The newspaper report of Paul Van Meer’s murder, which seeds suspicion and fear among the conspirators.

- The delayed sailing of the SS Nianga due to an oil pump malfunction—an early comic crisis.

- Gwendolen’s tall tales about her husband Harry Chelm’s importance and wealth, which complicate the gang’s plans.

- The car incident: Billy’s supposedly fatal crash and the mistaken report of his death, which opens a sequence of opportunistic moves.

- The dispatch box mystery aboard the ship, whose theft and reading accelerates paranoia and accusation.

- The ship’s engine failure and the passengers’ evacuation, which culminates in the beach landing and interrogation.

- The Scotland Yard intervention and final arrests.

Character Analysis and Principal Performances

Huston assembled an idiosyncratic, international cast that includes Humphrey Bogart as Billy Dannreuther, Jennifer Jones as Mrs. Gwendolen Chelm, Gina Lollobrigida as Maria Dannreuther, Robert Morley as Peterson, Peter Lorre as Julius O’Hara, Ivor Barnard as Major Jack Ross, Marco Tulli as Ravello, and Bernard Lee as Inspector Jack Clayton. The ensemble’s strengths come from its mixture of comic and dramatic talents. That mixture is essential to Huston’s experiment: the film requires actors who can sell menace and farce in the same breath.

Humphrey Bogart plays Billy with an unsteady charm—part survivor, part con man, part bemused romantic. His voice and manner are central to the film’s tone. (It’s notable, however, that Bogart lost several teeth during production, and the film resorted to dubbing by Peter Sellers for a brief period while Bogart recovered.) Jennifer Jones’s Gwendolen moves between daffy fantasy and dangerous mendacity; she invents and inflates details about her husband, and those fabrications have real consequences. Gina Lollobrigida, introduced to American audiences in the role of Maria, offers a lethal mix of flirtation and steel: Maria’s flirtations are never mere coquettishness—they’re tactical, a currency used to keep schemes afloat.

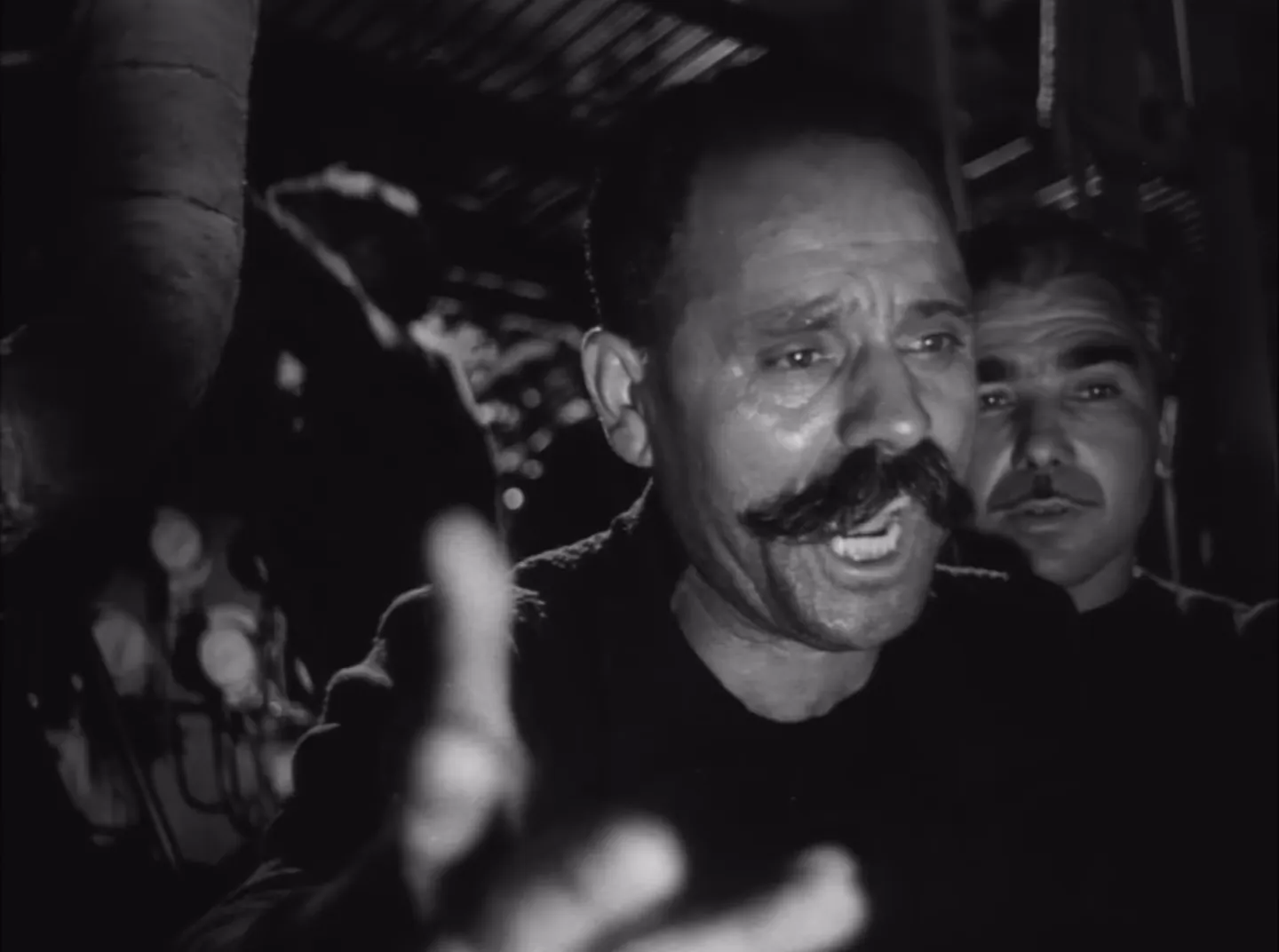

Robert Morley’s Peterson is the gang’s ostensible financier and the slickly corrupt foil to Billy’s uneasy conscience. Peter Lorre’s Julius O’Hara supplies a furtive, pungent nervousness that grounds many of the film’s comic moments. Ivor Barnard’s Major Ross is a carryover of military menace, a man whose swagger conceals lethal intent. Huston’s casting invites viewers to calibrate the performances: at times, the actors play straight to noir type; at others, they undermine it, making their gestures theatrical with intent.

Visual Style, Cinematography and the Noir Connection

Cinematographer Oswald Morris wraps Huston’s sardonic screenplay in a grim, neo-realistic photographic language—hard shadows, weathered faces and a world that looks lived-in and inhospitable. The film’s locations—shot largely around Ravello and the Amalfi Coast—provide an unusual backdrop for noir tropes: clear Mediterranean light, a sunlit port square, and beaches that read both as escape and exile. Huston deliberately displaces noir’s usual urban nightscape, creating a paradoxical effect: the film looks too real to feel like a pastiche, and too comic to feel like a straight noir. That duality is precisely why the picture circulates in critical conversation as a film noir movie that knowingly parodies itself.

Huston’s direction allows moments of stillness—faces in reaction, an interior lit by a single lamp—that recall the classical noir palette. Yet Huston punctures those moments with absurd dialogue or an improbable beat that deflates tension. It is this oscillation between seriousness and self-parody that both frustrates and rewards viewers: Beat the Devil often functions as a film noir movie in miniature, a set of noir signifiers stretched thin by comedic observation.

Examples of Visual Contradiction

- The opening conspirators shot: a composition that evokes noir ensemble scheming but staged in a bright room where shadows are not the point.

- The ship’s dispatch-box sequence: a claustrophobic exchange staged on a vessel where the sea horizon is always visible—threat contained yet open-ended.

- The African beach sequence: expansive and sunlit but narrated through tension and interrogation, making the location function as noir’s hostile world.

Key Dialogue Moments and Their Significance

The film’s dialogue—partly Huston’s, partly Capote’s—often trades in bravado and aphorism. Lines like “Time is a crook” or “To be trustworthy is not more important than to seem to be trustworthy” function as comic takes on philosophic noir maxims. The characters’ talk reveals moral inversion: they use the rhetoric of honor to justify betrayal, and they deploy intimacy to mask transactions. Huston stages these exchanges so that the audience is invited to laugh and to wince.

“Time is a crook.”

Such short, barbed lines compactly reveal a worldview: in Huston’s picture, time is not a neutral measure but an accomplice to greed. Characters measure their risk calculus not in ethics but in minutes and opportunities—a central preoccupation for any writer thinking about crime and chance, and one that situates Beat the Devil as a film noir movie that weaponizes humor.

Production Anecdotes and Their Effect on the Film

Production myths around Beat the Devil have contributed to its reputation. One well-known fact is that Humphrey Bogart lost teeth in an accident, a mishap that temporarily impacted his diction and required Peter Sellers—still an unknown—in a small dubbing role. The film’s shooting locations in Ravello and Atrani (Amalfi Coast) provide authentic Italian texture, and Huston’s improvised, day-to-day shooting method encouraged spontaneity. That improvisational approach is visible on screen: actors often riff, and scenes have a lived-in, elliptical quality that sometimes reads as comic brilliance and sometimes as thin plotting.

Stephen Sondheim’s presence on the film as a clapper boy is a delightful footnote: serious future figures in other arts passed through Huston’s set. The film’s editing history—where Huston later re-edited in response to previews, adding narration and restructuring—is another testament to its hybrid identity. Huston’s willingness to recast and reframe the story after early reactions shows his uneasy balancing of parody and narrative engine.

Reception Then and Now

Upon release, Beat the Devil confounded critics. Reviews described it as “roguish” and “conversational,” but often faulted the film for losing the novel’s sharper construction and bite. Some critics felt the film’s attempts at spoof wore thin. Humphrey Bogart himself reportedly disliked the final product, a reaction sometimes attributed to the film losing him money and certainly informed by his discomfort with its uneven tone.

Years later, the film accrued champion critics who saw the value in Huston’s gambit. Roger Ebert, for example, named Beat the Devil among his “Great Movies,” arguing that it anticipated camp sensibilities—an early, perhaps clumsy, experiment in a sensibility that became central to later cult appreciation. The film’s public-domain status for many years also allowed it a broader circulation, fostering its cult reputation as a film noir movie that doubles as a comedy of errors.

Legalities, Restorations and the 2016 Reappraisal

A major restoration in 2016 reignited interest in the film. Sony Pictures, in collaboration with The Film Foundation, restored the film to 4K and reinstated about four minutes that had been cut in earlier edits, bringing the runtime to roughly 93–94 minutes. This restoration corrected some of the film’s fractured reputation by reintroducing scenes that clarify motives and sustain pacing. The 2016 version is now copyrighted by Columbia Pictures, unlike the public-domain versions that circulated for decades.

The restoration’s reception affirmed what modern scholars had suspected: Huston’s film benefits from a decisive presentation. Restored footage and refined sound reveal subtleties in performance—small facial shifts and rhythmic beats of humor—that earlier rough prints obscured. The restoration also allowed reevaluations of the film’s connection to noir. With better image quality, the shadows, textures and compositions read with a sharper noir inflection, making the film’s deliberate parody feel more sophisticated.

Why Beat the Devil Can Be Read as a Film Noir Movie (and Why That Label Is Tricky)

To call Beat the Devil a film noir movie is to embrace nuance. On the one hand, it shares many noir markers: morally ambivalent protagonists, criminal schemes, betrayal, and a pessimistic take on human motives. Its characters are small-time crooks turned geopolitical players; its story hinges on murder, attempted murder and collusion with corrupt officers. The film’s visual language—harsh lighting, close-ups on anxious faces, an aesthetic that foregrounds found, decayed surfaces—echoes noir practice.

On the other hand, Huston self-consciously distances the film from noir solemnity. He uses farce to illuminate the same dark class anxieties and corrupt networks that noir usually prosecutes with tragedy. Where a typical film noir movie would unfold as slow, inexorable doom, Beat the Devil lets miscalculation and farce determine outcomes. The protagonist laughs at circumstance rather than succumbing to existential despair. Huston thus retools noir to make a critique not just of crime, but of grand illusions of empire, respectability and masculinity.

Specific Reasons the Film Aligns with Noir

- Character moral ambiguity: protagonists and antagonists share the same moral mud.

- Focus on criminal enterprise and the inevitability of exposure.

- Use of lighting and framing to suggest threat and claustrophobia even in wide-open spaces.

- Preoccupation with betrayal, deception and the consequences of greed.

Why the Label Remains Contested

- Beat the Devil intentionally undercuts noir’s moral seriousness with humor and parody.

- Its bright locations and comic beats contrast noir’s typical nocturnal urban moods.

- Huston’s satirical intent reframes noir devices as targets rather than as transparent ethical registers.

Given these considerations, Beat the Devil might best be described as a film that uses the toolset of a film noir movie to create a new effect: a corrosive comedy that leaves the viewer slightly disoriented about which register to trust. That is precisely the point.

Comparative Notes: Beat the Devil vs. The Maltese Falcon

Huston himself described Beat the Devil as “a sort of loose parody” of The Maltese Falcon—a film in which Huston had earlier cast Bogart in a classic noir lead. Where The Maltese Falcon is austere, tightly plotted and suffused with moral weight, Beat the Devil stretches the noir idiom until its seams show. The Maltese Falcon’s detective logic gives way, in Beat the Devil, to opportunistic scheming and caricature. Huston’s gesture here is not accidental nostalgia but a pointed reworking: he takes the apparatus of noir and lets it self-satirize.

Yet both films are linked by a common preoccupation with treasure and the social rituals that surround its pursuit. If The Maltese Falcon is a parable about obsession, Beat the Devil is a parable about the absurdity of obsession. Both, however, can be located within the larger category of a film noir movie at different points on the spectrum: one resolutely tragic, the other gleefully mocking.

Legacy and Influence

Beat the Devil’s odd mixture of terror and belly laughs influenced later writers, including Len Deighton—it was cited as an inspiration for The IPCRESS File. For scholars and fans, the film remains a test case for how genres can be bent and recombined. Its reexamination through restoration has helped reposition it from curiosity to experimental piece, and its long public-domain circulation made it a laboratory for film fans, students and programmers to test intuitions about taste, irony and camp.

Its continuing discussion in critical circles—whether it is a “success” or a “failed” experiment—makes Beat the Devil useful as a pedagogical tool. The film prompts conversations about the elasticity of genre: how much can noir absorb before it dissolves? Huston’s picture suggests a considerable amount.

Recommended Viewing Strategies for Modern Audiences

For viewers coming to Beat the Devil with a specific interest in the film noir movie tradition, the film works best when watched in two modes.

- First, watch it as a narrative experiment: pay attention to timing, interruptions and how Huston allows scenes to drift into improvisation. Note how narrative urgency is repeatedly neutralized by comic asides.

- Second, watch it as a study of character economy: follow how particular traits (Gwendolen’s fantasy-making, Peterson’s cold calculation, Billy’s pragmatic decency) orchestrate betrayals and reconciliations. This view will show how Huston uses noir archetypes as launching pads for satire.

Viewing with an eye for both registers will reveal the film’s strengths and its deliberate provocations. Rather than judging it against a strict noir canon, it is more fruitful to consider Beat the Devil as a film noir movie that asked new questions about genre conventions—questions that still resonate in contemporary genre-hybrid cinema.

Quotations as Windows into the Film’s World

Huston’s screenplay yields lines that read like thematic signposts. A handful stand out as evidence of the film’s self-aware play with noir philosophy:

“To be trustworthy is not more important than to seem to be trustworthy.”

“Time is a crook.”

“This generation's had its chance.”

Inserted in context, these lines serve as Huston’s winks: the film knows how noir talks and chooses to answer back in a different register.

Conclusion: Reclaiming a Mischievous Corner of Noir

Beat the Devil resists a single label. It is not simply a film noir movie nor merely a comedy; it is an audacious hybrid that deploys the language of noir to parody and interrogate the codes of criminality, empire and masculinity. Huston’s gamble—to let noir’s devices be both used and mocked—results in a film whose pleasures are intermittent and its provocations lasting.

Viewed today, especially in its restored form, Beat the Devil is a rich object for students of classic cinema who wish to explore genre elasticity. It rewards repeated viewings: each pass reveals new inflections in performance and new calibrations in tone. For those interested in the genealogy of noir and in how directors like Huston experimented with and subverted conventions, this picture is indispensable.

Finally, for the reader keen to dive deeper into Beat the Devil as a film noir movie and a cinematic oddity: treat the film as a classroom, not as a textbook. Let its inconsistencies teach rather than frustrate. Huston’s refusal to fit neatly into a category is precisely what gives the film its enduring pleasure.

How to Keep Exploring Classic Cinema

Those who enjoyed this reappraisal may want to explore Huston’s other work (most obviously The Maltese Falcon) and to compare how genre expectations are handled across his films. The restored Beat the Devil also invites listeners to sample other mid-century films that play with noir—either by embracing its fatalism or by parodying its myths. For subscribers and readers seeking deeper dives, a curated series of essays and screenings would illuminate not only Huston’s methods but also the broader currents of postwar film production and reception.

Note: This critical study has relied on the film and its documented records, and it aims to inspire further viewing and discussion among classic cinema enthusiasts. For those wanting a regular, in-depth dispatch on classic movies, consider subscribing to dedicated film criticism platforms that provide archival context, restoration notes and curated viewing lists. The world of the film noir movie is vast—Beat the Devil is one of its more mischievous corners.