Dangerous Money (1946), directed by Terry O. Morse and released by Monogram Pictures, occupies an intriguing corner of mid‑century American cinema. Framed as a tightly plotted detective vehicle starring Sidney Toler as Charlie Chan, the film unfolds almost entirely aboard an ocean liner bound for Samoa. It combines the serial familiarity of the Chan franchise with a compact, claustrophobic mystery that invites comparison with the darker sensibilities of the period. This review and analysis, written from the perspective of a classic cinema critic, examines the film’s narrative mechanics, production context, and aesthetic qualities—asking when and how a film like Dangerous Money can be treated as a film noir movie and what value such a reading adds to our appreciation of the work.

Note: The discussion relies on the film’s dramatic content and on published production history. The picture was directed by Terry O. Morse, produced by James S. Burkett, and distributed by Monogram Pictures in October 1946. Sidney Toler stars as Charlie Chan; Victor Sen Yung (billed as Victor Sen Young) appears as Jimmy Chan, Number Two Son, and Willie Best substitutes for the usual comic foil in the role of Chattanooga Brown. The film runs 66 minutes and was developed under the working title Hot Money.

Outline and Approach

- Introduction and production context

- Plot synopsis and structure

- Cast, performances, and production constraints

- Stylistic reading: can Dangerous Money be considered a film noir movie?

- Thematic concerns: crime, colonial spaces, and moral ambiguity

- Critical reception and legacy

- Conclusion: the film’s place in the Chan series and mid‑century genre conversation

Plot Synopsis: A Compact Ocean‑Liner Mystery

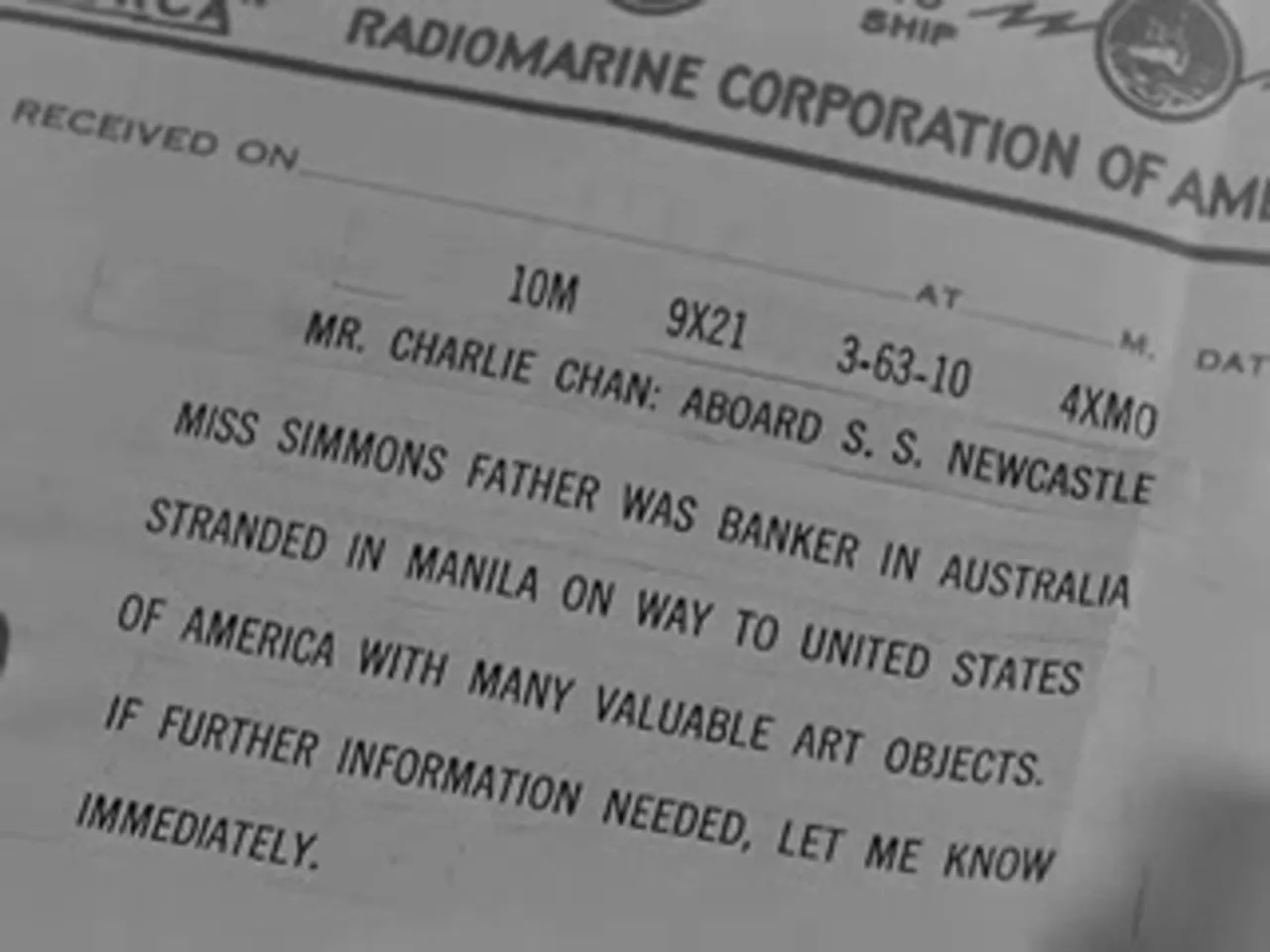

Dangerous Money compresses its action into a short, decisive season aboard a liner bound for Samoa. The narrative catalyst arrives when Scott Pearson, a United States Treasury agent, confides to Charlie Chan that he is tracking stolen currency and art plundered from Philippine banks during the Japanese occupation. The cargo—“hot money”—is circulating across the Pacific in large bills. Pearson is an undercover operative and reports that attempts have been made on his life since boarding. Chan takes up the investigation, only to find Pearson murdered with a knife to the back. The film converts the ship into a closed environment: passengers become potential suspects, shore leaves and side trips are constrained by time, and every corridor, salon, and cabin is a stage for interrogation and discovery.

From the outset the drama leans on a classic detective puzzle: who had motive, opportunity, and access to the murder weapon? The script threads a series of false leads—blackmail, stolen art, forged papers, furtive money traders—and fills out the suspect pool with the sort of colorful low- and mid‑level figures that populate closed‑room mysteries: the purser with a secret, the flirtatious young tourist with a past, a showman who practices knife‑throwing, the scientist with a fish museum ashore, a trader returning from Honolulu, and the ubiquitous local Kanaka whose knowledge of island networks makes him both vulnerable and useful. Chan’s methods—patient interview, fingerprinting experiments, traps for the killer, and the quiet application of deductive reason—drive the plot forward through a chain of small revelations toward exposure and capture.

Key Scenes and Pivotal Moments

The film stages several memorable moments that crystallize its mood and structure:

- The confidential meeting between the undercover Treasury agent Scott Pearson and Charlie Chan, which sets the central conflict in motion.

- The King Neptune ritual and the murder in the salon, where spectacle and violence collide.

- The fingerprinting experiment and the staged trap, which reveal the killer’s careful methods and hint at larger conspirators behind the scenes.

- The discovery of caches of currency and art in Professor Martin’s museum, the narrative’s inflection toward the wider theft network.

- The exposure of a false identity and the unmasking of a conspirator disguised as a woman—an unexpected reveal that plays on the film’s themes of disguise and illicit passage.

Cast and Production: Constraints, Substitutions, and Series Mechanics

Dangerous Money is one film in a long series built around the Charlie Chan character. Sidney Toler’s Charlie Chan had by 1946 become a reliable screen presence—an established, if formulaic, center for a familiar type of mystery. The Wikipedia production notes give us important context that affects both performance and reading: Toler was seriously ill with cancer during filming, and his mobility was limited. Monogram Pictures adapted by relying more heavily on supporting players. Victor Sen Yung returned as the Number Two Son, lightening Toler’s burden and supplying the often necessary comic and active counterpoint. Mantan Moreland, who had previously played Chan’s chauffeur Birmingham Brown, was unavailable (on tour with Ben Carter), so Monogram substituted Willie Best as Chattanooga Brown.

Those production decisions matter. The Chan series depended on a balance between the detective’s laconic wisdom and the energetic interventions of his sons or sidekicks. The substitution of Willie Best reconfigures that dynamic and alters the film’s tonal texture. Throughout Dangerous Money one can detect pipeline creativity: Monogram’s producers and director Terry O. Morse shaped the narrative to be economical, confined, and reliant on conversation rather than expensive sets or action sequences. Running 66 minutes, the film must move efficiently from exposition to denouement—a trait that aligns it with the brisk economy of many B‑pictures of the era.

Principal Cast

- Sidney Toler as Charlie Chan

- Victor Sen Yung as Jimmy Chan, Number Two Son

- Willie Best as Chattanooga Brown

- Rick Vallin as Tao Erickson

- Joseph Crehan as Captain Black

- John Harmon as Freddie Kirk

- Bruce Edwards as Harold Mayfair

- Dick Elliott as P.T. Burke

- Joseph Allen as George Brace, purser

- Gloria Warren as Rona Simmonds

- Tristram Coffin as Scott Pearson (the murdered Treasury agent)

- Emmett Vogan as Professor Martin

These players, familiar with the economy of B‑film acting, deliver what the script requires: a range of credible types, a capacity for quick, expository dialogue, and the ability to register ambiguity without lengthy psychological layering. The close confinement of the ship helps to compress characterization into gesture, line, and costume—everything must work quickly and efficiently.

Style and Direction: Is Dangerous Money a Film Noir Movie?

Labeling Dangerous Money a film noir movie is tempting and controversial. The phrase “film noir” carries both a set of stylistic signifiers—high‑contrast lighting, urban nightscapes, moral ambiguity, femme fatales—and a set of historical associations tied to postwar male anxiety, fatalism, and existential dread. Dangerous Money is not a canonical noir in the sense of Double Indemnity or The Maltese Falcon. It is a B‑mystery vehicle with a familiar detective—yet the film shares enough aesthetic and thematic concerns with noir to merit an exploratory reading.

First, consider atmosphere. The film’s setting—a fogged sea lane, cramped passageways, the noir‑friendly gloom of a ship at night—creates an exterior and interior sense of enclosure. The ocean liner substitutes for the city street: a liminal, transient space where identities are fluid, papers can be falsified, and fugitives can hide in plain sight. The salon, the cabin corridors, and the museum ashore become shadowed arenas where motives are revealed by light and gesture. The film stages scenes of uncertainty and concealment: a rope cut to enable a stealthy approach, a knife thrown with surgical precision, and the sudden, cruel interruption of spectacle by murder. These are noir‑adjacent motifs—criminality masked by civility, spectacle giving way to violence, the lurking threat of money and corruption.

Second, the thematic presence of postwar dislocation—represented by the stolen Philippine currency and art—gives the story a geopolitical edge. The “hot money” motif is more than a MacGuffin; it is a symbol of wartime dispossession and postwar profiteering. The Pacific, recast as a sort of frontier for illicit capital, makes the film an economic noir: where traditional noir often framed corruption in the context of domestic greed or urban vice, Dangerous Money explicitly ties crime to wartime looting and the lucrative transnational trafficking that followed. The stolen art and the circulation of illicit bills suggest a world in which legal order and moral authority have been loosened by war—an environment prime for noir interrogation.

Third, the film cultivates moral ambiguity. Many characters possess compromised motives—blackmailers, deniable lovers, traders who profit from instability. Even the showman and the purser harbor secrets. Charlie Chan’s detective methods—methodical, moral, and ultimately restorative—stand in contrast to the murkiness around him, but the narrative does not present a simple world of good and evil; rather, it stages a contest among shades of compromise until the detective imposes a form of order. In this sense Dangerous Money shares noir’s preoccupation with compromised institutions and the brittle distinction between law and profit.

However, the film diverges from classic noir in tone and resolution. Charlie Chan’s paternal certainty and the film’s eventual restoration of order—criminals are exposed, the stolen art is recovered, and the captain’s authority is reinforced—keep Dangerous Money tethered to the classic detective film tradition more than to fatalist noir. Where film noir often ends in ambiguity or moral defeat, Dangerous Money ends in a conventional triumph of detection. Its moral economy is conservative: wrongdoing is punished and authority is reasserted. That concluding clarity reduces Dangerous Money’s claim to the label film noir movie, but not entirely: it remains a useful lens for examining the film’s darker surfaces.

Visual Texture and Sound

The production’s economy extends to cinematography and sound. William A. Sickner’s camerawork and the film’s editing create a functional, serviceable visual style that emphasizes clarity and pace over formal bravura. Still, the film makes efficient use of frame and shadow: conversations in cabins are lit to emphasize faces and glances; the salon scene—loud with spectacle—suddenly contracts into a cluster of dark shapes around a body. Edward J. Kay’s music supports mood rather than directing it; the score accentuates mystery and tension at key moments, but rarely dominates. The film’s sound design—dialogue‑led, rapid—reflects its soapbox‑to‑whodunit lineage and the need to keep exposition moving.

Character Work and Performance Notes

Sidney Toler brings to the role of Charlie Chan a well‑worn, economical intelligence. Even while ill, Toler’s Chan is a presence of calm reasoning. His bedside manner, dry aphorisms, and meticulous methods anchor the film’s moral compass. Victor Sen Yung returns as Jimmy Chan, affording the elder Chan several opportunities to delegate action. Willie Best’s Chattanooga Brown provides a lighter counterpoint, though his performance must be read against the complex racially inflected dynamics of 1940s cinema—an issue addressed below.

Gloria Warren’s Rona Simmonds supplies the film’s emotional center: a young woman traveling under potentially false papers with a crush on the purser. Warren’s performance registers earnestness and vulnerability; her character’s predicament—tied to stolen art entrusted to her father—generates sympathy and complicates the accusation culture aboard the ship. Similarly, the presence of Professor Martin and his wife introduces an academic, museum‑centric subplot that culminates in the discovery of hidden caches of money and art in the professor’s museum ashore.

Tristram Coffin as Scott Pearson provides the initial incitement; his murder—brief and shocking—pushes the film’s characters into a collective role as suspects and investigators. The ensemble, accustomed to B‑film rhythms, moves through their parts with the briskness demanded by a 66‑minute runtime.

Race, Representation, and the Chan Formula

Any modern analysis of the Charlie Chan series must grapple with its complex racial politics. Charlie Chan is a fictional Chinese detective created by Earl Derr Biggers; on screen, however, the role was traditionally portrayed by non‑Asian actors—including Warner Oland and Sidney Toler—whose performances combined respect for the character’s intelligence with a stylized accent and aphoristic delivery. Dangerous Money continues that tradition. The cinematic Chan is an inscrutable figure whose wisdom and moral authority often contrast with the stereotypes around him, but the casting and comic devices of the series complicate how contemporary audiences perceive representation.

Moreover, the substitution of Willie Best in place of Mantan Moreland alters the dynamic between Chan and his comic foil. Best’s Chattanooga Brown contributes comic relief but does so within the constraints of a period in which African‑American performers were often relegated to stereotypical roles. The production notes from the film’s history explain that Moreland was touring with Ben Carter and therefore unavailable, and that Best substituted to maintain the series’ camaraderie—yet that substitution does not erase questions about the representation of race and comedy in 1940s Hollywood. A modern critic must acknowledge the historical context and read these elements critically: the Chan pictures offered a kind of cross‑cultural appeal while simultaneously reflecting the prejudices and industrial practices of their era.

Money, Empire, and the Postwar Unsettling

Dangerous Money’s central conceit—the circulation of stolen currency and art removed from Philippine banks during World War II—grounds the film in a broader imperial and economic history. The film’s “hot money” is not simply a plot device. It stands in for the chaotic flows of wealth that often accompany conflict: looted currency, preserved art, and the opportunistic traders who move in the aftermath. In situating its crime in the Pacific theater, the film implicitly touches on wartime disruption and the murky postwar marketplace. That focus gives the narrative a geopolitical weight unusual in a routine detective series entry: the crime is not merely personal greed, but a symptom of global dislocation.

For viewers attuned to historical specificity, the film’s concentration on currency and art recovery reads as an acknowledgement—if a simplified one—of wartime loss and restitution. That the film recovers many of the art objects and finds the stolen cash hidden in Professor Martin’s museum hedges toward a conservative closure: the recovery of cultural and economic property, the restoration of legal order, the triumph of the detective who is also, in effect, a guardian of rightful possession. Noir cinema often refuses such tidy resolutions, but Dangerous Money’s ethical conservatism aligns it with the popular detective tradition in which order is reconstituted by the end.

Fingerprinting and Forensic Play: Science as Sleight‑of‑Hand

One of the film’s more playful strands revolves around Charlie Chan’s forensic staging: a fingerprinting experiment, the planting of a cut rope, staged traps for the knife‑thrower, and the collection of prints from various implements and surfaces. These scenes exhibit the midcentury screen fascination with detective science—an appeal that the public shared in the aftermath of wartime technical innovations. The film’s sequence in which fingerprints are discovered, rubbed off, smeared with oil, or hidden by gloves becomes a miniature essay on the limits of detection: sometimes science reveals the truth, and sometimes it only delineates the cleverness of the criminal.

The forensic motif supports a theme: the detective cannot rely solely on one method. Chan combines science with observation and an understanding of human motive. In this matrix, the film suggests a modernist faith in applied knowledge while acknowledging its fallibility—an ambivalent stance that is itself noir‑adjacent.

Reception: Contemporary and Retrospective Views

Contemporary trade responses preserved in the film’s production history offer qualified approval. Motion Picture Daily’s Thalia Bell described Dangerous Money as “typical murder mystery in typical Chan style,” praising Toler’s familiar characterization and the reliable comic contributions of Victor Sen Yung and Willie Best. Showmen’s Trade Review noted that the confined setting (the ship) slowed the picture compared with more expansive entries, but predicted that such limitations “shouldn’t hinder its acceptance,” citing Toler’s smooth and able performance in a role that had become second nature.

The film was produced as low‑budget fare for Monogram Pictures, a studio adept at creating efficient genre pictures with ready audiences. Its working title—Hot Money—points to the economic pressures that structured the picture’s conception. Dangerous Money’s release in October 1946 placed it in a postwar market hungry for both escapism and puzzle‑driven entertainment. For fans of the Chan series, the film delivered the expected ration of aphoristic wisdom, careful deduction, and the reassertion of order.

Legacy and Public Domain Status

Dangerous Money is presumed to be in the public domain, due to the omission of a valid copyright notice on its original prints. That status has helped the film survive in circulation in ways that other studio‑controlled properties have not—print availability and online access have introduced the picture to new audiences and to scholars interested in the epochal transition of detective and noir modes in the mid‑1940s. The film is therefore a useful artifact for studying B‑unit production practices, serial detective formulas, and the era’s negotiation with wartime consequences.

Reading the Ending: Order Reinsured, Questions Unanswered

In Dangerous Money’s denouement, Charlie Chan reveals the ring of conspirators and the secret stowage of money and art. A disguised conspirator—revealed to be a man posing as the presumed wife of an accomplice—unmasks the film’s central theme of disguise. The narrative ends with the captain contented that the brig will be full and with Chan’s economy of summation: practical closure, retrieval of the stolen objects, and the exposure of those who profited from wartime theft. For viewers who prefer clarity and moral resolution, this ending will satisfy; for those seeking the ambiguous moral collapse typical of the pure film noir movie, the ending may read as conservative and restorative.

Yet this restoration contains a caveat. The film’s focus on the movement of illicit capital and the circulations that evade national jurisdiction suggests that disorder persists beyond the ship’s rails; capturing the ring on a single voyage does not solve the systemic dynamics that enabled the crime in the first place. In this sense Dangerous Money offers a restrained critique: it reveals the possibility of detection while reminding the audience of the vastness of the illicit networks that persist in the wake of global conflict.

Why Consider Dangerous Money as a Film Noir Movie?

Labeling Dangerous Money as a film noir movie rests on a synthesis of style, theme, and historical context. The film evokes noir through its:

- shadowed, enclosed spaces and an overall sense of atmospheric confinement;

- themes of betrayal, disguise, and the corrosive influence of money;

- existential tenor tied to postwar restitution, displacement, and the moral slippery slope of profiteering;

- ambivalence toward authority and the limits of forensic certainty.

These elements together make a compelling case for reading the film as an interstitial work—neither full‑blooded noir nor purely a formulaic detective picture, but a film that borrows noir’s questions while maintaining the detective genre’s ultimate confidence in rational resolution. For critics and historians, Dangerous Money offers a vantage point from which to study how low‑budget studios and serial franchises absorbed noir anxieties without fully converting to noir’s aesthetic and ideological commitments.

Enduring Strengths and Limitations

Dangerous Money’s strengths are straightforward: economy of plot, succinct staging, and the steady moral presence of Sidney Toler’s Chan. The close quarters of the liner sharpen the mystery and provide the director with a clear dramatic limitation that the film uses to its advantage. The incorporation of wartime looting and stolen art adds narrative depth, situating the crime within a broader geopolitical frame.

Limitations are not negligible. The film’s production values and brief runtime constrain character development; many supporting figures function as types rather than fully rounded personalities. Racial and ethnic representation, a recurring problem in the series, remains problematic from a contemporary perspective. The substitution of Willie Best for Mantan Moreland solves an immediate production need but does not address the deeper structural issues of how Black and Asian characters were written and utilized in Hollywood at the time.

Watching Today: A Guide for the Modern Viewer

For contemporary viewers approaching Dangerous Money with curiosity about vintage mystery cinema and the film noir movie lineage, several points may enhance the viewing experience:

- Appreciate the compact craftsmanship. The film is a model of economical storytelling; accept its brevity and evaluate how effectively it stages motive and discovery within an hour and six minutes.

- Look for the interplay between spectacle and violence. The salon ceremony—King Neptune’s court—turns public ritual into a stage for private murder; this collision is a recurring locus of moral inversion in noirish narratives.

- Watch the forensic sequences. The film’s engagement with fingerprinting and staged traps reflects a midcentury fascination with the possibilities and limitations of scientific detection.

- Consider the wartime setting. The film’s concern with stolen Philippine currency and art anchors it historically; seeing the movie in the context of 1946 changes the stakes of its mystery.

- Maintain a critical eye on representation. Acknowledge the film’s historical context while evaluating its portrayals of race and the implications of casting choices.

Conclusion: Dangerous Money’s Place in Genre Conversation

Dangerous Money is a compact, efficient entry in the Charlie Chan series that merits reconsideration. As an artifact of Monogram Pictures’ postwar production strategy, it demonstrates how serial detectives could absorb and refigure anxieties about money, power, and identity in the aftermath of global conflict. From a stylistic and thematic standpoint, the film edges toward noir: its atmosphere of confinement, moral ambiguity surrounding stolen capital, and the interplay of disguise and detection resonate with film noir movie concerns. Yet it retains the detective tradition’s restorative impulse—Charlie Chan’s reasoned closure reasserts order and recovers stolen objects—so Dangerous Money comfortably sits between the two modes.

For cinephiles, students of genre, and those interested in the intersection of popular detective formulae and postwar cultural history, Dangerous Money presents a rewarding case study. It reveals how a modest production can harness its constraints to raise questions about crime and the circulation of capital, how a stable franchise can adapt to production challenges, and how the detective figure mediates between unsettled historical realities and a desire for moral clarity. Read as a film noir movie in an expanded sense—one attentive to atmosphere, uncertainty, and the corrosive power of illicit wealth—Dangerous Money offers a compact, instructive example of mid‑century genre crosscurrents.

Sidney Toler’s Chan may not epitomize noir pessimism, but the film’s shadows, secret stashes, and moral skepticism retain the capacity to intrigue. Dangerous Money invites a dual appreciation: for its craftsmanship as a tight detective thriller, and for the ways it hints at noir’s darker questions without surrendering to nihilism.

Selected Quotations and Notable Lines

- “I’ve been assigned to investigate this hot money that’s appeared among the islands.” — the inciting statement that frames the film’s geopolitical stakes.

- “No one can leave Ceylon until Mr. Chan releases you.” — a line that underlines the ship as a closed system, the classic setting for a locked‑room drama.

- “Only old‑fashioned criminals leave such evidence behind.” — a wry invocation of evolving forensic methods and the film’s engagement with modern detection.

- “Perhaps knife never touched by human hands.” — a moment that underscores the film’s preoccupation with disguise, craft, and the limits of evidence.

Dangerous Money endures as a cinematic curiosity: short, sharp, and reflective of its era. It is thus worth viewing both on its own terms and as part of a larger conversation about how mid‑century American film dealt with the aftermath of war, the circulation of illicit capital, and the shifting boundaries between detective story and noir sensibility. In the overlapping light of those concerns it remains an instructive and occasionally surprising specimen of a film noir movie’s influence on B‑picture mystery storytelling.