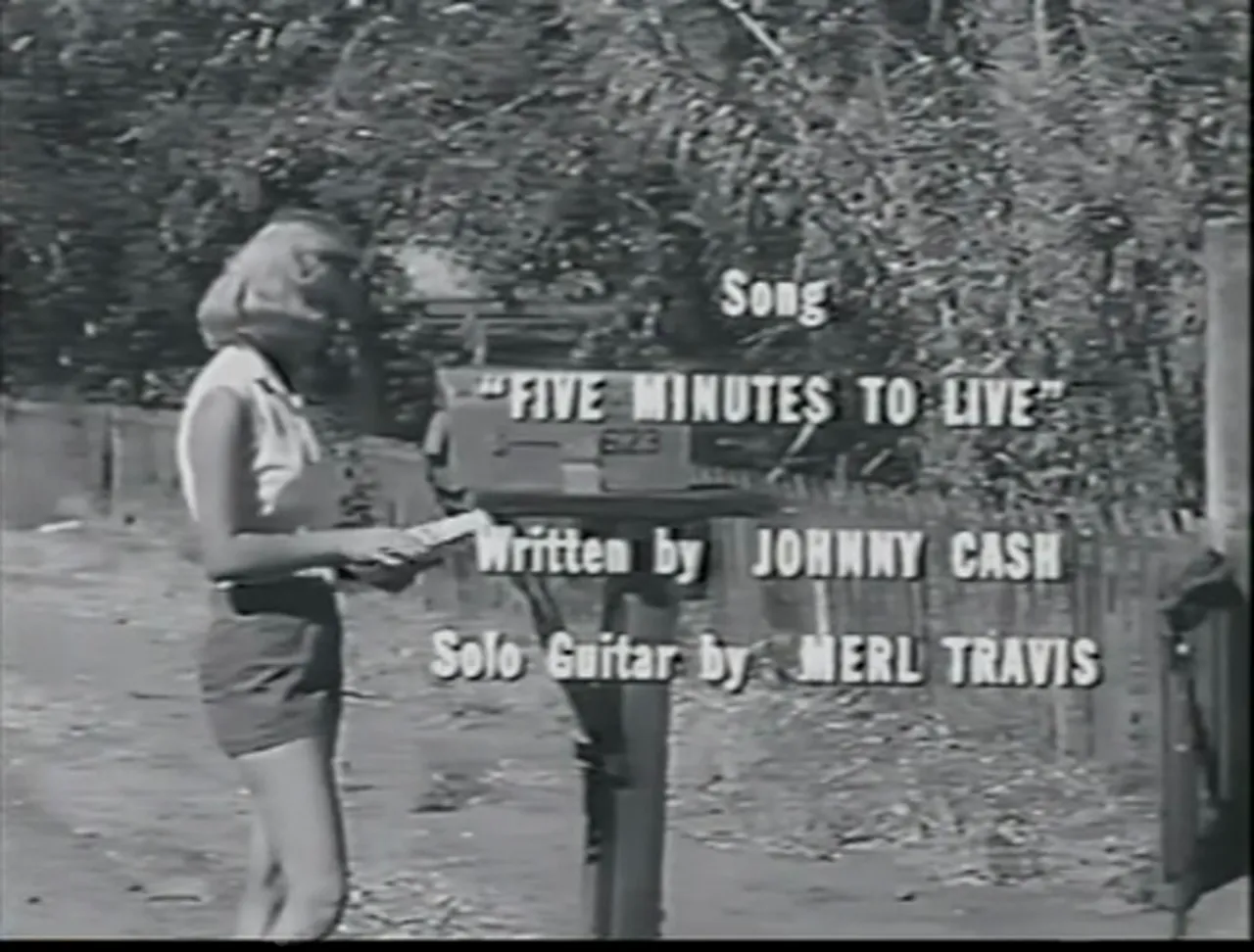

Presented with a compact, relentless runtime and a notorious centerpiece performance by a future country music legend, this film noir movie—Five Minutes to Live—arrives like a cold wind through an open window. The original video presentation by its creator offers a measured playing of the film’s beats and the critic in the piece leans on that presentation; the classic cinema critic who writes here has used the original video and the film’s Wikipedia entry as the dual sources for a careful reassessment. This film noir movie, directed by Bill Karn and released in December 1961, remains a succinct specimen of neo-noir crime cinema—raw, economical, and dangerously theatrical.

Outline: How this critique proceeds

- Introduction and context: what Five Minutes to Live is as a film noir movie

- Detailed plot analysis: setup, escalation, and denouement

- Performances and casting: Johnny Cash and an ensemble of players

- Direction, screenplay, and the film’s compact construction

- Technical craft: cinematography, editing, music, and production values

- Themes, motifs, and noir pedigree

- Reception, box office, and legacy

- Concluding verdict and lasting significance as a film noir movie

Introduction and context: what makes this a film noir movie

Five Minutes to Live occupies a specific niche: it is described in period and later references as a neo-noir crime film. As a film noir movie, it trades on stark moral choices, intimate violence, and a sense of inevitability. The Wikipedia record identifies it as a 1961 American neo-noir crime film directed by Bill Karn, starring Johnny Cash in his first theatrical film role. This film noir movie was produced on a modest budget of $300,000, distributed by Sutton Pictures, and performed well at the box office relative to cost, reportedly grossing over five million dollars—a remarkable return for a compact production. As a film noir movie, it is less an epic drama than an intense, scene-by-scene squeeze of suspense and character.

Plot summary: economy of set pieces in a film noir movie

At its most basic, Five Minutes to Live is a tight piece of storytelling. Fred Dorella, a man with experience in crime, tells his tale in a framing device that reveals the mechanics of a meticulously planned bank heist. He partnered with Johnny Cabot to hold a woman hostage while Dorella would bring the ransom across a bank counter. That woman is Nancy Wilson, wife of Ken Wilson, vice-president of the Harper Federal Trust. The plan hinges on repetition and routine—precisely the things small towns excel at—and on a cruelly literal five-minute schedule of telephone calls that will prove, if not controlled, then decisive.

The film noir movie compresses the action: Cabot waits outside the Wilson house, ingratiates himself with a door-to-door pretense (a guitar instructor), and inserts himself into domestic space. Meanwhile, Dorella visits Ken at the bank and demands a $70,000 draft, tying the demand to the clocks and the five-minute intervals that punctuate the narrative. The film noir movie builds schematically: call—pause—threat—response. The tension becomes unbearable not through long set pieces but through repeated, escalating small scenes, each with its own moral test.

How the five-minute device shapes the film noir movie

The signature conceit is elegantly simple and brutally effective. Five minutes is both a literal device and a thematic instrument: characters must decide under an artificially constrained timeframe. Time, in this film noir movie, functions as a weapon. The ticking clock is not background noise; it is the antagonist. Dorella’s insistence that Ken must answer each five-minute mark or his wife will die gives the plot a mechanical certainty that pushes characters into revealing choices. It is a film noir movie tactic that renders psychology transparent: who breaks first, who bargains, who rationalizes, and who proves true to an inner sense of decency.

Performances and casting: the high-wire of unexpected faces in a film noir movie

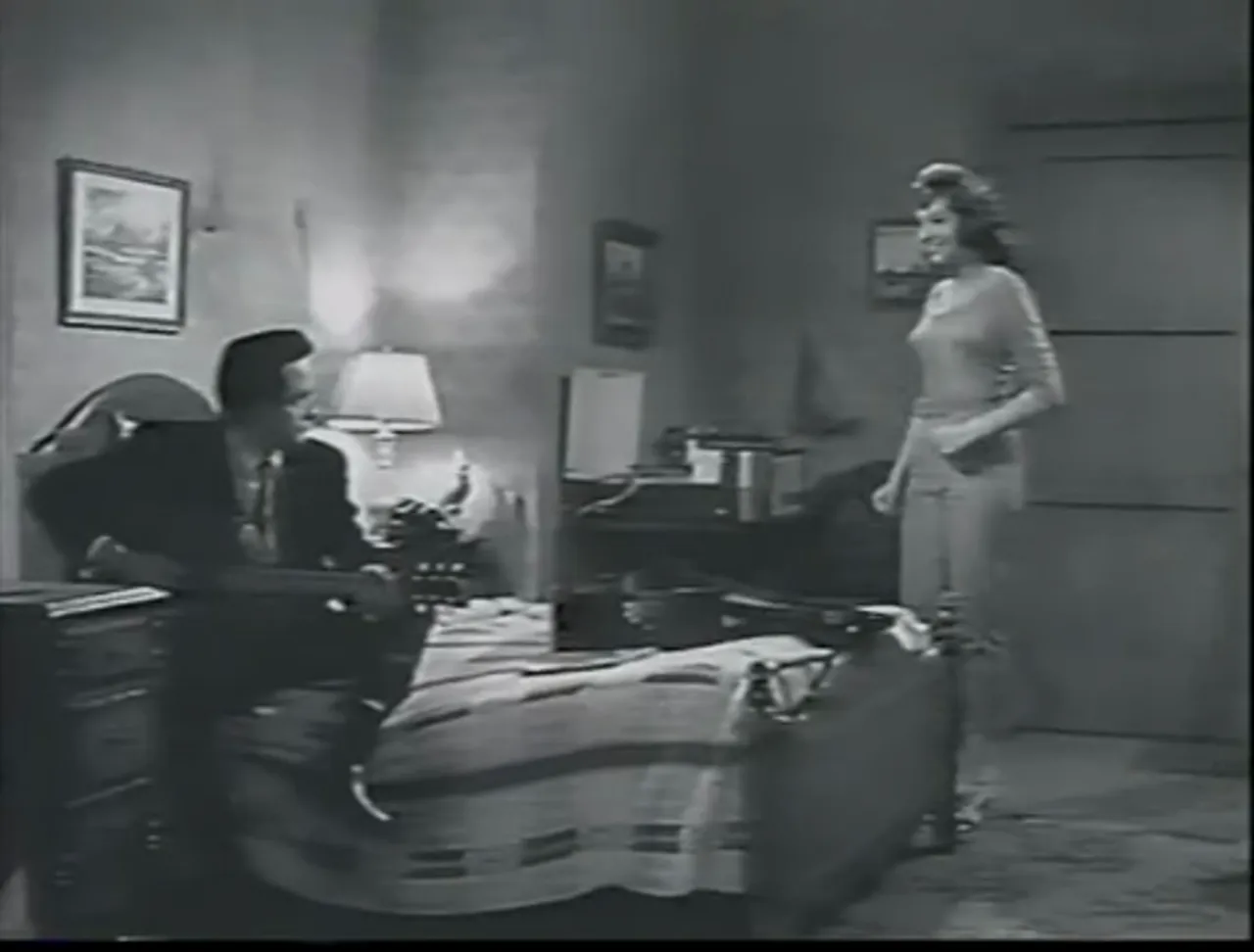

Few casting bills look as surprising on paper as Johnny Cash’s name in the credits of a film noir movie. The Wikipedia entry confirms Cash’s appearance as Johnny Cabot, in his first theatrical film role. Cash was a star of popular music, not a trained dramatic actor, and the casting choice gives the film noir movie an idiosyncratic gravity. Cash’s laconic presence and musical authority make him suitable to the role of a man who threatens domestic calm with a guitar and low menace. In a film noir movie sense, Cabot is part menace, part caricature, and part social outsider—someone whose arrival in Camellia Gardens cracks the veneer of placid suburbia.

Vic Tayback plays Fred Dorella, the architect of the crime, and his performance anchors the film noir movie’s central moral monologue. Donald Woods inhabits Ken Wilson, the banker compromised by his own private life and tempted to moral abdication. Cay Forrester wrote the screenplay and stars as Nancy Wilson, the woman whose safety is the medium of the plot’s ethical tests. Ron Howard (credited as Ronnie Howard) appears as Bobby Wilson, the child who later becomes instrumental to the film noir movie’s climax. Merle Travis appears in a cameo as Max and contributes the guitar solo to the title song—an explicit intersection of music and menace that is a hallmark of this film noir movie.

Johnny Cash in context: a performative gamble that pays

Johnny Cash brings an authentic streak of the American outlaw to his role. He is not a classical actor with trained range, and that is precisely the advantage. In this film noir movie, authenticity matters more than polish. Cash’s measured cadence and the way he uses the guitar as a prop and a weapon give the film noir movie a signature mood. Moreover, Cash performing the title song, with Merle Travis on a guitar solo, embeds the film noir movie with a musical identity that reads like a commentary: the music itself is part of the menace.

Direction and screenplay: Bill Karn and Cay Forrester’s compact design for a film noir movie

Director Bill Karn and screenwriter Cay Forrester work within a strict economy of time and scene. The screenplay is adapted from a story by Palmer Thompson, but it is Forrester’s tight scripting that gives the film noir movie its rhythm. The dialogue is lean, the beats recur, and the camera stays close where it must. The film noir movie’s 80-minute runtime imposes no fat; every scene either advances the moral jeopardy or deepens characterization.

Forrester’s structural choice to frame the film with Dorella recounting the robbery is significant. As told in the narrative, Dorella’s recollection allows the film noir movie to trade in a kind of deferred revelation: audience knowledge outpaces some characters and lags behind others. The retelling device also permits a critique of criminal hubris—the telling of a crime story in confident, almost theatrical terms that collapse when confronted by unpredictable human variables (a child at the wrong place at the wrong time, a husband’s unexpected conscience). This is classic film noir movie irony: the plan’s cold precision undone by messy life.

Staging and pace: how the screenplay serves the film noir movie

The screenplay moves like a metronome. The literal ticking between phone calls, the repeated departures and returns, and the incremental tightening of the screws all function as rhythmic devices. They create suspense through repetition, not through spectacle. The film noir movie therefore feels like a piece of chamber theatre translated into cinema: claustrophobic, relentlessly focused, and morally unavoidable. That economy of staging also allows for moments of black comedy—when cab drivers, neighbors, and women’s club committees enter the plot, they reveal social texture and offer respite from the main current of violence while also underscoring the commonplace that absorbs evil.

Technical craft: cinematography, editing, music, and production values in a film noir movie

The craft of Five Minutes to Live leans on the essentials. Carl E. Guthrie is credited as cinematographer; his work is functional and effective for a film noir movie that relies on shadow and the compression of interior spaces. The editing by Donald Nosseck keeps scenes brisk and ensures that the small-town setting never dilutes the film noir movie’s momentum. With an 80-minute runtime, the film noir movie must be lean, so editing choices are decisive: there are no indulgent slow-burn sequences, only concise, focused collisions.

Music plays a curious role in this film noir movie. Johnny Cash performs the title song, and Merle Travis contributes a guitar solo—an unusual casting of musical performance as an element of menace. The soundtrack is economical and serves as both diegetic sound (the guitar in Cabot’s hands) and an extradiegetic commentary on the character’s mood. The treatment of music makes this film noir movie feel distinctly American—rooted in the musical idioms of the time and the persona of its star.

Production values versus box-office return: the economics of a film noir movie

Reportedly produced for $300,000 and returning roughly $5.6 million at the box office, this film noir movie illustrates an era of filmmaking where concise storytelling could yield substantial commercial returns. The production companies—Somera Productions and Flower Film Productions—kept the picture compact and shootable. The modest budget required creative problem-solving and favored performances over expensive sets. The film noir movie’s monetary success suggests that audiences responded to its urgency and novelty, perhaps drawn by Johnny Cash’s star power and the film’s terse promise of danger.

Themes, motifs, and noir pedigree: why this qualifies as a film noir movie

Five Minutes to Live is not noir in the classic 1940s sense of elaborate urban shadows and polyamorous scheming, but it is a film noir movie in spirit and in function. Neo-noir, the category that Wikipedia assigns, is a useful designation: the film inherits noir themes (fatalism, moral ambiguity, the presence of a criminal anti-hero) and translates them into a lean crime thriller. The motifs are familiar: time as sentence, routine as vulnerability, domesticity as a fragile mask, and a charismatic outsider who reveals the rotten center.

The film noir movie’s moral core concerns choices under pressure. Ken Wilson is central; his secret intention to leave Nancy for a mistress at first appears to be moral corruption, and Dorella’s presumption that Ken will let his wife die seems plausible. Yet Ken cracks and consents to pay the ransom—a complicated mixture of self-interest and fear. The film noir movie interrogates whether private desires can survive public threat. It asks whether a man who contemplates infidelity will also allow a human life to be bartered for a clean exit. Film noir movie narratives delight in such tests, and this film adheres strictly to that pleasure.

Suburbia as dark stage: the film noir movie’s setting matters

Camellia Gardens is not just a setting; it is a character in this film noir movie. The small town’s orderliness—the women’s club, the predictable breakfast times, the rituals of children—creates the conditions for Dorella’s scheme. Inverting the pastoral image of suburbia, the film noir movie shows that monotony breeds predictability, which in turn invites exploitation. The presence of the women’s club, in particular, functions as a chorus that comments on social standards without perceiving the rot beneath them. The film noir movie therefore uses the small town as a foil to urban crime narratives, showing that evil is not exclusively metropolitan.

Climactic architecture and the moral resolution in a film noir movie

The climax is compact and, for a film noir movie, devastatingly direct. Johnny Cabot’s increasing nervousness after not receiving the call, Bobby’s unexpected return home, and the arrival of the police produce an escalation that is inevitable once the five-minute cycle is interrupted. The film noir movie does not allow for a cinematic contrivance of redemption through long monologues; instead, its moral resolution is violent and immediate. Cabot is shot and killed by police; Bobby’s staged pretend-dead act—an unglamorous, resourceful trick—saves him and allows Nancy to collapse into maternal relief. In this film noir movie, salvations are small and improvisational rather than grandiose.

Irony and the final turn: the film noir movie’s last note

The film noir movie ends with a domestic and moral reversal: Ken drives off to Las Vegas not with his mistress but with Nancy, having learned the durability of love—or at least the practical consequences of real danger. Dorella finishes telling his story to the police, and the narrative frames return to legal and social order. There is a bitter irony here common to film noir movie outcomes: those who manufactured the scheme are undone, while those subject to the scheme survive by a mixture of courage, luck, and, in Bobby’s case, improvisation. The film noir movie thus refuses the melodramatic redemption typical of less severe thrillers and settles instead for a sober, realistic wind-down.

Reception, box office, and legacy: how the film noir movie fared

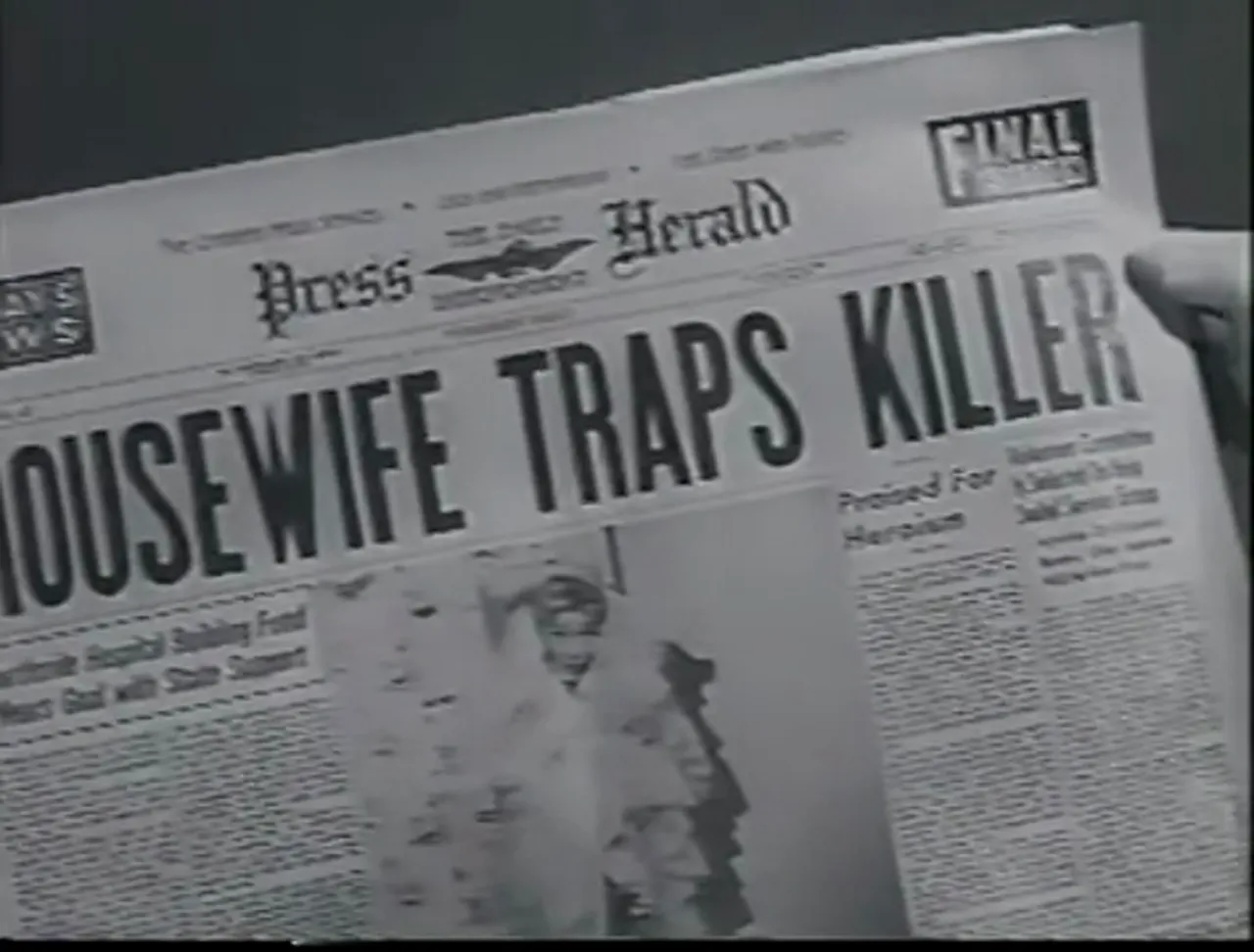

According to the record maintained on Wikipedia, Five Minutes to Live was released on December 7, 1961, and yielded a notable box office return relative to its budget. Its budget is listed at $300,000 with a reported box office of $5,655,000. The disparity between cost and gross marks it as a commercial success. The presence of Johnny Cash likely contributed to public interest; his crossover appeal as a music star created a curiosity factor that the film noir movie leveraged.

Critical standing and reissues: the film noir movie’s afterlife

Over time, the film noir movie has come to be appreciated as a compact curiosity: a neo-noir crime film that nests a music star in the heart of a crime story. In 1966, the picture was retitled Door-to-Door Maniac for a reissue by American International Pictures—an example of how marketing reframed the film noir movie for different audiences. The film’s relative brevity and focus made it suitable for double bills and reissues, and its availability through archives and online platforms allows contemporary viewers to reassess its merits as a film noir movie artifact.

Casting notes and curiosities: the film noir movie’s surprising roster

The cast list reads like a patchwork of familiar and surprising names. In addition to Johnny Cash, the film includes Donald Woods (Ken Wilson), Cay Forrester (Nancy Wilson), Pamela Mason (Ellen Harcourt), and Vic Tayback (Fred Dorella). Ron Howard appears as Bobby Wilson—credited as Ronnie Howard—making this film noir movie also a notable early entry in the career of a future Hollywood figure. Merle Travis’s appearance and guitar solo provide musical texture, and Midge Ware, Norma Varden, and others fill out the social milieu that the film noir movie depicts.

- Johnny Cash as Johnny Cabot

- Donald Woods as Ken Wilson

- Cay Forrester as Nancy Wilson

- Pamela Mason as Ellen Harcourt

- Vic Tayback as Fred Dorella

- Ron (Ronnie) Howard as Bobby Wilson

- Merle Travis as Max

- Midge Ware as Doris Johnson

- Norma Varden as Priscilla Auerbach

Style, genre placement, and the film noir movie’s aesthetic

Where does Five Minutes to Live sit in the broader spectrum of noir? It fits the definition of a film noir movie through its preoccupation with crime as existential test, its focus on character choices under pressure, and its use of bleak outcomes. However, it departs from the long shadows and femme fatale dynamics of classical noir by framing the drama in domestic space and by using repetitive timing as a structural engine. For some viewers, the film noir movie reads as a hybrid: part social drama, part crime procedural, all stripped-down noir. Neo-noir is the proper label because the film updates noir themes into a later cinematic climate defined by shorter runtimes and a willingness to mix popular music with menace.

Why scholars and fans of the film noir movie revisit it

There are a number of reasons students of cinema revisit this film noir movie. First, it is historically interesting for featuring Johnny Cash’s first theatrical role and for Merle Travis’s musical contribution. Second, its narrative economy offers a case study in how to build suspense without spectacle. Third, the film noir movie’s small-town inversion of noir settings provides an alternative take on how crime and morality operate outside of large cities. The film’s commercial success relative to budget also invites analysis of how compact films found audiences in the early 1960s.

Remake prospects and the film noir movie’s cultural aftershocks

Interest in the title persisted: a proposed remake announced in 2012 would have been directed by Jan de Bont, according to records. That project never fully materialized, but the notion of remaking this film noir movie emphasizes its continued appeal as a tight premise that can be retooled for modern sensibilities. The concise premise—hostage, clock, moral test—lends itself to reinterpretation in contemporary contexts where domestic threats and surveillance culture heighten the stakes.

Close reading: emblematic scenes in the film noir movie

Several scenes deserve focused attention for how they condense the film noir movie’s themes and techniques.

- The planning sequence: Dorella’s outline of the scheme foregrounds the five-minute cycle. The camera is discrete; the dialogue is crisp. This is the film noir movie’s manifesto: crime as choreography.

- Cabot’s door-to-door entry: Pretending to be a guitar instructor, Cabot crosses the threshold and transforms domesticity into theatre. The film noir movie stages the invasion as a cultural trespass—music turned to weapon.

- The bank confrontation: The $70,000 draft scene is the moral furnace where Ken Wilson is tested. The film noir movie excels in showing how power and social standing do not inoculate from moral panic.

- The phone-clock cadence: The repeated calls and the theater of waiting define the film noir movie’s tension generation. Here time is compressive and oppressive.

- The shootout and Bobby’s improvisation: The climax is both tragic and tender; Bobby’s play-acting saves him and breaks the antagonist. As a film noir movie endnote, it emphasizes the unpredictable human element that defeats cold calculation.

Critical perspective: strengths and limitations of the film noir movie

Strengths:

- Extreme narrative economy—80 minutes used to maximum effect in this film noir movie.

- Strong central performances that rely more on presence than technique, notably Johnny Cash’s idiosyncratic screen persona.

- An original structural device in the five-minute cycle that organizes suspense.

- Use of music as an element of menace, uniquely tying the star’s gifts to the film noir movie’s mood.

Limitations:

- Some characters, by necessity of brevity, remain schematic; the film noir movie’s compressed time leaves little space for incremental psychological depth.

- The plotting relies on precise coincidences (a child returning at the dramatic moment) that, while effective, are also contrivances typical of small-scale thrillers rather than sprawling noir epics.

- Production values are modest; some viewers may find the staging and camera work functional rather than formally innovative for a film noir movie.

Audience and academic interest: who should watch this film noir movie?

Students of noir and neo-noir, fans of Johnny Cash, and cinephiles who appreciate compact thrillers will find Five Minutes to Live worth revisiting. For scholars, it provides an efficient case study in how noir themes adapt to post-classic era constraints. For casual viewers, the film noir movie’s short length and straightforward plotting make it an accessible introduction to the moral architecture of noir without the density of longer masterpieces. Importantly, its historical context—early 1960s crime cinema—situates it at a transition point between studio-era noir and the more experimental tendencies of later decades.

Legacy and availability: preserving this film noir movie for modern viewers

The film noir movie’s afterlife includes reissues and inclusion in film catalogs; its availability through archives and online platforms has enabled new viewings. The Wikipedia record mentions its retitled rerelease—Door-to-Door Maniac—by American International Pictures in 1966, and it points to resources such as the AFI Catalog, IMDb, and the Internet Archive for access. The film noir movie’s modest production and enduring premise suggest it will continue to surface in retrospectives of neo-noir and crime films.

Conclusion: Five Minutes to Live as a compact and telling film noir movie

Five Minutes to Live stands as a concentrated demonstration of what a film noir movie can be in a compact form: it is a tale of mechanical crime undone by messy life; a moral probe that uses time as a blade; and a platform on which a singular star—Johnny Cash—leaves an indelible mark. As a film noir movie, it is not grandly ambitious, but it is ruthlessly effective. Its success at the box office for its budget is no accident: the film noir movie produces immediate, shareable tensions and a narrative that rewards viewers who appreciate efficiency and edge.

Final thoughts from a classic cinema critic

Viewed now, Five Minutes to Live reads as both an artifact and a compact moral drama. The film noir movie’s economy should be studied by filmmakers who want to learn how to generate suspense without spectacle. Johnny Cash’s screen presence offers historians a glimpse into how star persona can remake a role, while Cay Forrester’s screenplay demonstrates how a single structural conceit can sustain a whole film noir movie. For the classic cinema enthusiast—and for potential subscribers interested in curated, critical perspectives—this film noir movie is a rewarding subject that blends popular culture and moral inquiry into an eighty-minute pulse.

For readers who cherish classic cinema and want deeper explorations into similar works, the critic recommends seeking out the film noir movie’s contemporaries and later neo-noirs. Consider the films that also use constrained time or domestic invasion as the engine of suspense. Fans of Johnny Cash’s music will find it interesting to experience his performance in cinematic context and to note how the film noir movie uses sound and musical persona to intensify psychological pressure.

Essentials at a glance for fans of the film noir movie

- Title: Five Minutes to Live (also reissued as Door-to-Door Maniac)

- Director: Bill Karn

- Screenplay: Cay Forrester (from a story by Palmer Thompson)

- Principal cast: Johnny Cash, Donald Woods, Cay Forrester, Vic Tayback, Ron (Ronnie) Howard

- Runtime: 80 minutes

- Release date: December 7, 1961 (United States)

- Budget and box office: $300,000 budget; approximately $5,655,000 gross

- Why watch: Compact, tense neo-noir; Johnny Cash’s first theatrical role; a memorable five-minute structural conceit

Encouragement to explore and subscribe

For readers who enjoyed this critical deep dive into Five Minutes to Live as a film noir movie, consider subscribing for curated essays that comb classic and neo-noir cinema for formal lessons, historical resonance, and cultural context. A subscription supports sustained research, archival retrieval, and close readings that illuminate why modest films like this film noir movie continue to matter. The film noir movie’s compact power exemplifies how economy of means can produce abundance of consequence; further pieces will continue to unpack other films of similar scale and ambition.

In short: Five Minutes to Live is a tight, effective film noir movie whose modest production and surprising casting have earned it a permanent place among curious, instructive noir works. It is recommended to anyone who wants to see how suspense can be built out of rhythm, routine, and the ordinary domestic clock—the same clock that, in this film noir movie, ultimately decides the fate of men, women, and children.