John G. Blystone's Great Guy — directed by Blystone and starring James Cagney — provides a compact, vigorous study in municipal corruption and the stubborn rectitude of a single determined inspector. This article examines that filmed adaptation and its cinematic context to offer a critic's appraisal. The piece places the picture within the tradition of the film noir movie while treating it as a distinct 1936 crime drama that channels the noir impulse — moral ambiguity, shadowy alliances, and a protagonist who refuses compromise.

The analysis looks closely at representative scenes, key lines, and the film's production pedigree, and it argues that although the film predates the classical noir era’s canonical period, it shares enough of noir’s DNA to make a useful study for anyone interested in the evolution of the film noir movie.

Outline

- Introduction: situating Great Guy and the film noir movie context

- Plot synopsis: the arc of Johnny Cave and the weights-and-measures crusade

- Major themes: honesty, civic duty, organized corruption

- Character study: Johnny Cave, Janet Henry, Marty Cavanaugh, Abel Canning

- Selected scenes and cinematic beats (with screenshots)

- Production background: James Cagney, Grand National Pictures, and the screenplay’s origins

- Critical reception and historical legacy

- Why Great Guy matters to lovers of the film noir movie

- Conclusion and viewing recommendations

Introduction: Why Great Guy still matters in a film noir movie conversation

Great Guy is a 1936 American crime picture that might be overlooked by viewers focused exclusively on the later, darker masterpieces of noir. Yet it offers a startling, compact portrait of political fixers, crooked merchants, and an incorruptible inspector who will not bend. The film stars James Cagney as Johnny Cave, an inspector from the New York Department of Weights and Measures, and it dramatizes a conflict that is both local and systemic: petty fraud and wide-reaching graft. The project sits squarely within the lineage that leads toward the film noir movie: it portrays institutional corruption, morally complex adversaries, and a protagonist whose toughness and moral clarity both attract admiration and provoke resistance.

For the classic film scholar or the curious cinephile, Great Guy is a revealing artifact. It predates the mid-1940s to mid-1950s period traditionally granted the label "film noir," but its concerns, its urban textures, and its willingness to show well-placed respectability as cover for venality anticipate the noir sensibility. In this way, it is instructive to place the film in an extended genealogy of the film noir movie — as ancestor and as contemporary that shares the same moral anxieties.

Plot synopsis: the straightforward fight against crooked measures

At its narrative core, Great Guy is simple, almost stripped down: the Department of Weights and Measures is meant to protect ordinary consumers from the everyday theft of shorted goods and false measures. Joel Green, the department chief deputy, is crippled by an apparent automobile accident engineered by corrupt political forces; before he is incapacitated he summons Johnny Cave and entrusts him with the prosecution of the racket. Cave accepts the job and becomes chief deputy. The film then follows his field work and the mounting confrontation with crooked merchants, a ward politician named Marty Cavanaugh, and — ultimately — a seemingly respectable local magnate, Abel Canning, who funnels stolen goods to a charitable orphanage and pockets the difference.

A plot summary cannot do justice to the film’s episodic force: Johnny’s day-to-day inspections reveal lead weights hidden in chicken carcasses, short gas tanks that shortchange drivers, and the casual, barely concealed bribes offered by merchants who regard the department’s oversight as an inconvenient tax on profit. Each vignette sharpens the film’s satirical edge. The drama escalates as Johnny refuses a cushy job meant to silence him and then faces a frame-up and direct attempts to rob him of his evidence. He survives a multi-layered conspiracy of politicians and criminals, recovers the stolen proof, and ultimately exposes the combination of elected authority and private fraud. By the denouement, which involves a raid on an apartment and a public unmasking, the honest inspector’s course restores both justice and his relationship with his fiancée.

Great Guy’s arc — from the small-scale sting operations to a larger confrontation with the machinery of municipal graft — maps an arc familiar in crime cinema and is one reason the film functions as a proto film noir movie.

Major themes: honesty, duty, and the quotidian sources of corruption

Three themes dominate Great Guy: the moral importance of seemingly small work, the corrosive alliance between politics and commerce, and the stubborn, almost romantic figure of the man who refuses compromise. The film insists that the Department of Weights and Measures matters because of its impact on ordinary households. One of the best lines — both clear in the original film and emphasized in the contemporary summary — explains the arithmetic succinctly: about 40% of American income is spent on food, and a small percentage stolen across a wide population “adds up” to an enormous sum. The script insists that the petty cheating of a single grocer is not petty at all; it is a civic theft when multiplied by millions of transactions.

That arithmetic gives Great Guy its moral justification. The space of the film’s action is not the glamorous crime world but the street-level economies of markets and storefronts. The film’s antagonists are not cartoonish gangsters but ward politicians and respectable businessmen who depend on a system of protection and the toleration of fraud. The public face of philanthropy and the private pocketing of goods is a theme the film explores with deliberate irony, and this civic-targeted corruption is an essential element of what later film noir movies would intensify: crime that lives inside institutions and behind the façade of respectability.

Finally, the protagonist, Johnny Cave, stands for a kind of tough-minded decency: he is not naïve, he is direct and rough-hewn, but he exhibits a moral clarity that refuses to be swayed by bribes or flattering offers. The film’s hero is an anti-hero by some standards — he is not suave, and he gets into fistfights — but his moral center is unambiguous. The way Great Guy frames his ethics makes the film an instructive case for critics interested in how American cinema modeled integrity during the 1930s.

Character study

James Cagney as Johnny Cave: the honest inspector

James Cagney’s Johnny Cave is the film’s living engine. Cagney — who by this point had established a persona across multiple pictures — brings a combination of rapid-fire energy, pugnacious charm, and moral certitude. Unlike the slick, cynical protagonists who would populate many later noir pictures, Johnny is rougher around the edges, part brawler and part moral crusader. He inspects poultry for lead weights and confronts politicians with equal vigor. Cagney’s performance is central; the film was the first of two he made for Grand National Pictures after his exit from Warner Bros., and its casting of Cagney underscores the production’s desire to anchor the narrative in an actor who could sell both toughness and a populist sincerity.

Johnny’s tactics are straightforward: he fines, he lectures, and he refuses cash offers. When confronted with the political machine’s offer of an easy out — an appointment to a higher government position that would neutralize his crusade — he declines. That refusal is a key moral pivot. He rejects the cushy role because it would sacrifice the everyday enforcement his department provides. That decision, filmed with Cagney’s characteristic physical intensity, embodies the film’s central message about the value of small-scale civic work.

Janet Henry: the fiancée and the moral tension

Janet Henry functions as both emotional ballast and a moral foil. She loves Johnny, but she is exasperated by his unwavering stubbornness, especially when his investigations threaten to upend her life. Her reaction to Johnny’s decision to publish the orphanage story — upsetting him, breaking their engagement temporarily — dramatizes the personal price exacted by public honesty. The film uses their relationship to remind viewers that the fight against corruption includes private sacrifice.

Marty Cavanaugh and Abel Canning: the two faces of corruption

Marty Cavanaugh is the ward politician: brash, blunt, and openly willing to protect his rackets with violence. Abel Canning, by contrast, wears the mask of respectability. He presents as a philanthropist but uses his position to shortchange an orphanage and line his own pockets. The film stages their contrast and eventual alliance to show how political muscle and economic respectability can combine into a reinforced system of predation.

Selected scenes and cinematic beats

Great Guy moves as a montage of small triumphs and escalating threats. The film’s structure — from the opening hospital scene to the climactic apartment raid — earns its momentum by building the stakes slowly but insistently. The following are representative scenes that reveal how the screenplay and direction emphasize moral clarity through procedural detail.

Hospital opening: urgency and appointment of the hero

The film opens with Joel Green in the hospital, a wounded man who insists on passing responsibility to Johnny Cave. The scene frames the narrative impetus: the old guard is taken out, the newcomer is anointed, and the work must continue. Green’s urgency and Johnny’s acceptance introduce the film’s central conflict quickly. The hospital setting functions as a relay station: the department’s institutional continuity moves from a wounded custodian to a combative successor.

Field inspections: discovery of lead weights and short measures

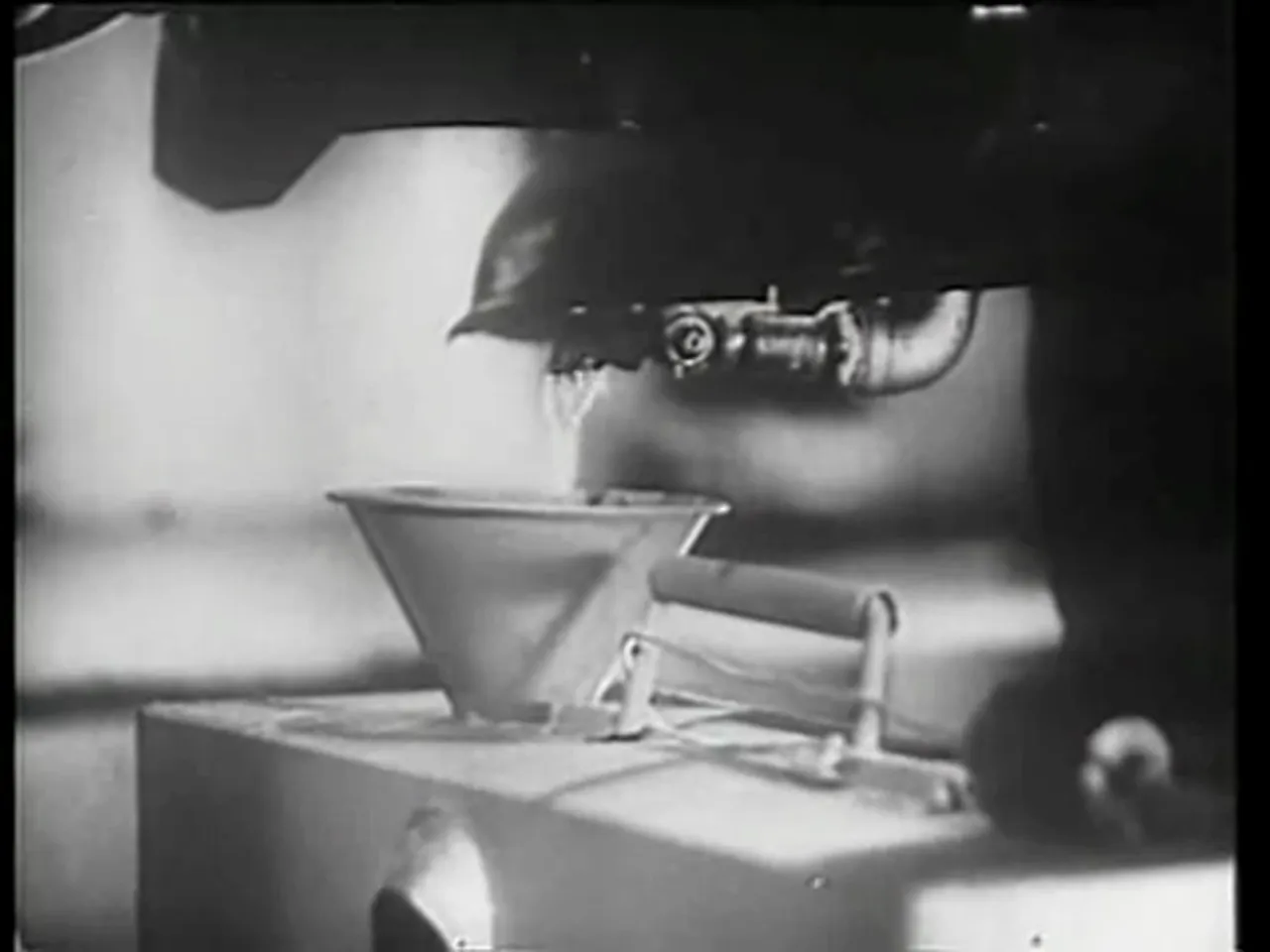

Great Guy invests surprising screen time in the act of inspection — weighing chickens, measuring sugar, testing gas tanks. These sequences are not merely procedural; they are moral scenes. The discovery of lead concealed in stewing chickens is staged with a mix of humor and anger: the inspector’s indignation is both cathartic and instructional. The film repeatedly affirms that the work of the department, though prosaic, directly protects the public. The cinematic effect resembles documentary detail at times, and those details make the stakes concrete.

The political offer and the moral crossroads

When the mayor and others try to buy Johnny’s compliance by offering him a more lucrative, higher-profile job on the Governor’s Tax Commission, the film stages a temptation. Johnny refuses. The decision is less about monetary reward than about responsibility and principle. It is one of the film’s clearest moral declarations: integrity in office cannot be merely scaled up; it must be maintained in the places where people actually live and spend.

The blackmail and the cocktail party: a noir-inflected set piece

One of the film’s most compelling sequences occurs at a cocktail party where politics, entertainment, and a criminal subplot intersect. Canning’s interaction with Joe Burton — the hired thug — and the exchange of a check in return for a key to an apartment are staged with an air of social theater and moral collapse. This scene functions like a noir set piece: respectable faces in elegant surroundings conceal venality and fraud. It is the film’s most urbane betrayal and evidences why Great Guy can be read through the lens of a film noir movie.

The final raid and the recovery of the evidence

The climax, in which Johnny discovers the hidden papers, prevents their destruction, and arranges for a police arrival, resolves the central mystery while dramatizing the close, decisive action that cinema appreciates. The arrest of Canning and Cavanaugh restores, for the moment, the moral order. The film concludes on a note of reconciliation: Janet and Johnny’s engagement is repaired, and Johnny offers a ring purchased on the installment plan — a humorous nod to the very economic concerns that have animated his crusade.

Production background and historical context

Great Guy was directed by John G. Blystone and released in December 1936. The film was made for Grand National Pictures and was the first of two pictures James Cagney made for that independent company after his break with Warner Brothers. According to the film’s production notes, the story grew out of a collection of pieces that appeared in The Saturday Evening Post in 1933 and 1934, written by James Edward Grant. The screenplay evolved through contributions by Henry McCarty and Henry Johnson, with additional dialogue credited to Henry Ruskin.

The production employed a technical adviser with real-world authority: Charles M. Fuller, the Los Angeles County Sealer of Weights and Measures. That choice underlines the film’s insistence on procedural authenticity. From the lead weights in chickens to the short-measured tanks, the film’s operational details benefit from the consultancy of a subject-matter expert.

James Cagney’s tenure at Grand National was brief but consequential. He had secured a release from his Warner Brothers contract and made Great Guy as part of a short-lived independent phase. The project reflected Cagney’s interest in roles that allowed his bracing energy and American working-class persona to be fully on display. He followed Great Guy with the musical Something to Sing About, but after that commercial disappointment he returned to Warner Bros. The Grand National period remains a fascinating sidelight in Cagney’s career and offers a compact example of an actor fully inhabiting both popular toughness and a moralized screen presence.

Screenplay, source, and adaptation

The story by James Edward Grant — “The Johnnie Cave Stories” — supplied a structural and tonal backbone: short, episodic tales that together built a social problem picture. Early press materials listed several writers, and the final credits show a collaborative process: writing evolved through several hands, but the film retained the insistence on concrete, street-level detail. The film’s reliance on semi-documentary evidence, combined with a populist moral thrust, gives it a didactic yet entertaining quality.

Reception, critical appraisal, and legacy

Contemporary and later critical opinion highlights several strengths in Great Guy. Notably, Graham Greene praised the film in 1937 for Cagney's performance, calling it "more sophisticated humour than usual" and admired the sequences that portrayed politicians and philanthropists as "pleasantly phosphorescent with corruption," singling out the film’s climax at an evening party as admirable. Greene’s review recognizes the film’s satiric eye and its vivacity; that verdict remains instructive: Great Guy is a morally pointed picture that also possesses a comic energy that stops short of mere sermonizing.

On a historical level, Great Guy is valued for several reasons. It documents James Cagney in a non-Warner role; it showcases how crime and civic life intersect; and it anticipates noir by showing how respectable contexts can house criminal acts. The film also benefits from its public-domain status in some markets and from availability on archive platforms, which have helped maintain its visibility for classic film enthusiasts. Its modest length — 66 minutes — makes it an efficient, compact study suitable for cinephiles, students, and instructors examining the transition to noir sensibilities in American cinema.

Great Guy as an antecedent to the film noir movie

How should a critic place Great Guy in relation to the classic film noir movie? The banded answer is: usefully and partially. Classic film noir commonly names a set of stylistic and thematic traits: urban settings, moral ambiguity, femme fatales, shadowy cinematography, and a postwar sense of social dislocation. Great Guy lacks many of the stylistic signatures commonly associated with noir — its lighting is not the chiaroscuro of the later 1940s, its heroine is not a femme fatale, and its ending restores basic moral order in a way many noir films refuse to do. Yet the film shares noir’s moral concerns: corrupt institutions, the fragility of civic trust, and protagonists who stand in sharp relief against a compromised urban environment.

In other words, Great Guy is not strictly a film noir movie as later critics would define the term; it does, however, share thematic DNA with the noir tradition. It dramatizes how respectability can be a cover for theft; it frames criminality as intimate with political power; it relies on urban textures and small-scale procedural detail to tell a moral tale; and it portrays a protagonist whose righteous stubbornness both makes him a hero and invites violent reprisals. By these measures, Great Guy is an important step in a narrative and thematic lineage that leads to the fully matured film noir movie of the 1940s and 1950s.

Performance highlights and supporting cast

The film’s supporting cast offers memorable turns that frame Cagney’s central performance. Mae Clarke’s Janet provides an honest emotional counterweight, and James Burke’s Patrick James “Aloysius” Haley contributes a comic, naïve presence that lightens the film’s darker edges. Robert Gleckler as Marty Cavanaugh is the archetypal ward-boss antagonist: coarse, confident, and untroubled by legality. Henry Kolker’s Abel Canning is especially important: his public philanthropy and private venality make him an effective antagonist precisely because his respectability is the very instrument of his theft.

Edward Brophy, Joe Sawyer, Mary Gordon, Wallis Clark, and others populate the world with figures that emphasize the film’s social reach — from market proprietors to police captains. The ensemble underscores the film’s thesis: crimes against the public are not the work of isolated criminals alone, but of networks that include those who can manipulate law, money, and moral appearances.

Technical notes: cinematography and advisory support

Jack MacKenzie handled cinematography and Russell F. Schoemgarth edited the film. The choice of Charles M. Fuller as a technical adviser is particularly noteworthy: his role as Los Angeles County Sealer of Weights and Measures brought operational accuracy to the film’s inspection scenes. The film’s attention to detail — how to weigh chickens, how to test sugar, how to detect short gas tanks — gives it a quasi-documentary clarity. Those moments of close inspection are the film’s signature: they turn the drama into a civic procedural, and the camera records the facts with clear-eyed precision.

Contextualizing Cagney’s Grand National interlude

James Cagney’s engagement with Grand National Pictures is an important production context. He left Warner Bros. and made two films for the independent company; Great Guy was the first. The arrangement allowed Cagney a degree of independence, and Great Guy’s populist themes and brisk pacing play to his strengths. However, the independent venture would be short-lived: after his second film, Something to Sing About, failed commercially, Cagney returned to Warner Bros. The Grand National period therefore stands as a brief experiment in star autonomy, and Great Guy represents a successful, if short-run, hybrid of commercial entertainment and moralized social problem storytelling.

Critical legacy and how to approach the film today

Great Guy’s legacy is modest but meaningful. It is not a foundational text in the film noir movie canon, but it is a worthwhile precursor: it reveals early cinematic responses to municipal corruption and the politics of vice. Contemporary viewers who seek a lean, efficient crime film with an ethical center will find Great Guy satisfying. It is also a helpful film for students of genre history: by comparing its procedural thrust and moral clarity to later noir’s ambiguities and fatalisms, one can trace how the nation’s cinematic anxieties about modern urban life evolved across the 1930s and 1940s.

For anyone teaching or writing about the evolution of the film noir movie, Great Guy offers a concentrated case study: it demonstrates how social problem filmmaking and crime melodrama intersect. It shows the period’s concern with protecting consumers — an economic morality play — and it frames corruption as a systemic issue requiring public exposure and legal remedy. The film’s climax and the subsequent arrests demonstrate classical Hollywood’s faith in institutional remedies when a virtuous protagonist does the hard work of disclosure and enforcement.

Selected lines and notable dialogue

Great Guy contains lines that reveal its ethical and populist commitments. A few examples underscore how the script compresses its argument into memorable statements:

- "40% of the American income is spent on food." This line ties individual acts of cheating to national-scale consequences and provides the film's economic rationale.

- "Keep your head on your shoulders and your fists in your pockets." A counsel to restraint that also recognizes the necessity of physical courage in private enforcement.

- "I'll be subtle." / "You will have to be." An exchange that captures the film’s recognition that moral work sometimes requires tactical cleverness rather than mere force.

- Graham Greene’s appraisal that Cagney “seldom disappoints” and that the film's scenes are “pleasantly phosphorescent with corruption.” (quoted in contemporary press)

“Since you've been with the Department of Weights and Measures, your name has become a synonym for honesty.” — a line that encapsulates the film's celebration of practical integrity.

Viewing recommendations and where to find Great Guy

Great Guy remains available through public-domain channels and archival services. For students of classic cinema it is recommended as a short, instructive feature that complements more widely discussed works in the film noir movie lineage. Because the film runs just 66 minutes, it is an excellent piece for classroom screening and guided discussion. Its availability on archive platforms helps preserve access, and the film’s short running time makes it easy to pair alongside a later noir for comparative analysis: for instance, pairing Great Guy with a mid-1940s noir will clearly highlight how moral tone and cinematic style shifted across a decade.

Conclusion: Great Guy’s enduring value for classic film study and noir genealogy

Great Guy is a compact, forceful depiction of civic responsibility set against the persistent background of municipal corruption. It gives James Cagney an ideal vehicle: a role that utilizes his physicality, his edge, and his populist charisma. The film’s focus on everyday fraud — disguised weights, shorted goods, bribes, and the manipulation of charity — makes it a distinctive social-problem film that resonates with the later concerns of the film noir movie.

For the critic, scholar, and devoted classic film viewer, Great Guy is not a definitive film noir movie; rather, it is a valuable antecedent that helps explain how the American cinema came to dramatize institutional corruption and moral resilience. It provides clear procedural beats, an honest hero, and a narrative that insists on the importance of ordinary public administration. Viewed today, it stands as both an entertaining crime drama and a compact civic sermon: a film about the small work that keeps a city honest.

Ultimately, Great Guy’s place in history is secure: it preserves a moment when popular cinema could deliver both punch and principle. For those interested in the formation of noir themes and the career arc of James Cagney, the film rewards repeat viewings and conscientious analysis. Its concise runtime, credible detail, and unembarrassed moralizing make it a film to recommend to any student of the film noir movie and to anyone who appreciates cinema that insists on the dignity of straightforward public service.

Further reading and next steps for the interested viewer

Members of classic film societies, instructors designing a module on noir precursors, or casual viewers curious about Cagney’s independent phase should consult the film’s production history and critical reception as found in period reviews and the film’s encyclopedia record. Screening the film alongside later noirs will illuminate shifts in tone, visual design, and national mood. For those making classroom syllabi, pairing Great Guy with a canonical noir — to contrast moral closure against tragic ambiguity — will produce lively debate about the period’s cinematic ethics and its evolving urban imagination.

Great Guy is short, pointed, and morally earnest. It repays careful attention because it demonstrates how popular cinema in the mid-1930s addressed consumer protection, municipal graft, and the fragile duty of public servants. Though not a canonical film noir movie by strict stylistic standards, its thematic kinship with noir gives it an indispensable slot in the history of American crime films.