The classic serial Holt of the Secret Service arrives on the page as a vigorous example of studio-era cliffhanger storytelling — produced by Larry Darmour, directed by James W. Horne, and released by Columbia Pictures in November 1941. The critic approaches it as one might examine a film noir movie: attentive to atmosphere, performance, moral tenor, and the mechanics of suspense. While Holt of the Secret Service is not a film noir movie in the strict stylistic sense, its shadowy criminal world, moral certainties, and relentless pacing reward close reading from the perspective of noir-informed criticism. This review and contextual essay treats the serial both as a period entertainment and as an artifact of classical Hollywood’s serial craftsmanship, offering scene-level commentary, production background from contemporary records, and a critical appraisal designed to guide enthusiasts and collectors.

Outline

- Introduction and initial framing

- Historical and production context

- Synopsis of the opening chapter (Chaotic Creek) with scene commentary

- Key performances and casting choices

- Direction, pacing, and the mechanics of serial suspense

- The serial’s relationship to noir sensibilities

- Reception, marketing, and legacy

- Preservation and availability

- Concluding thoughts and why the serial still matters

Introduction: Serial Adventure and the Critic’s Gaze

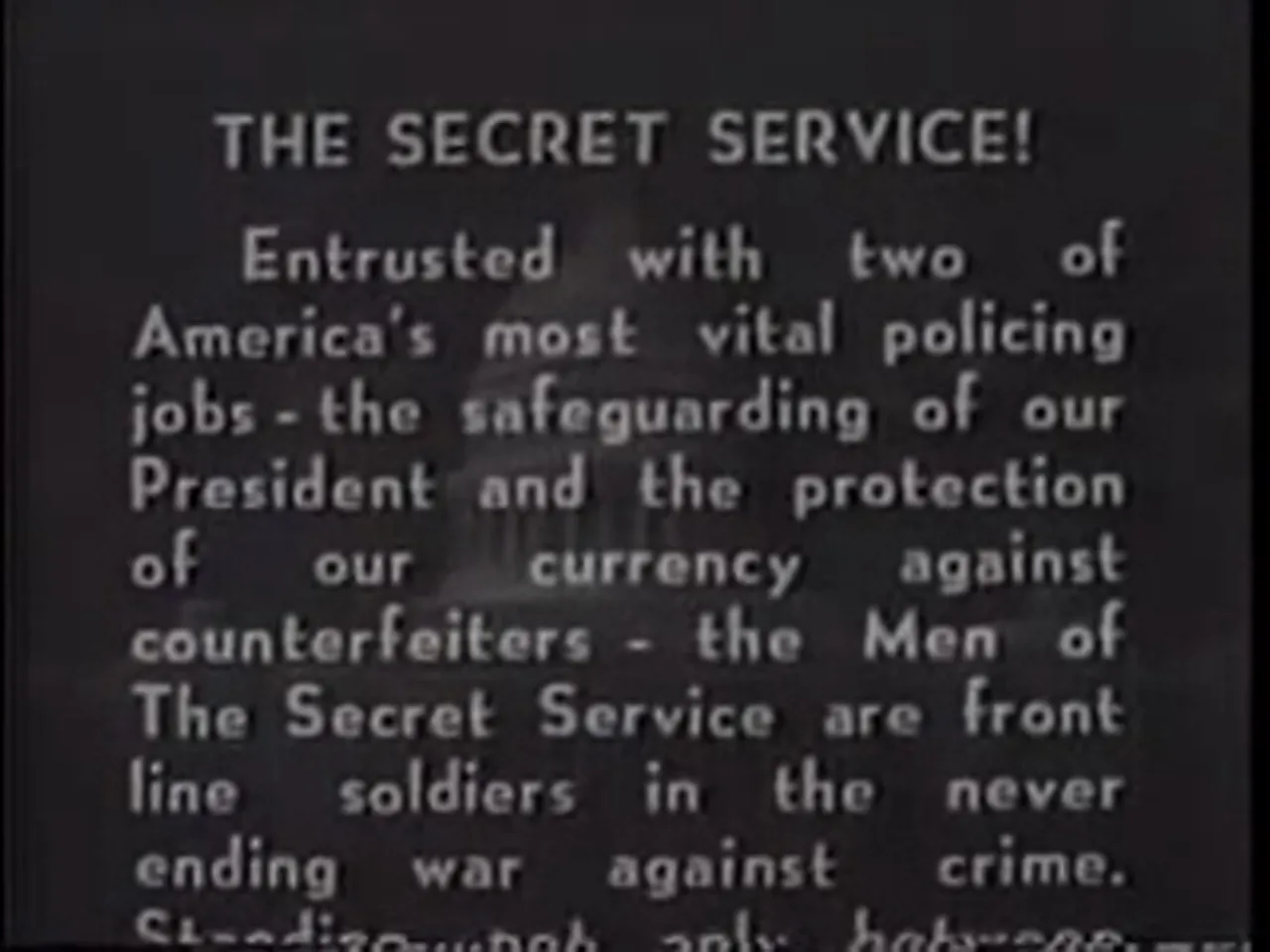

Holt of the Secret Service is a 15-episode serial with a running time of roughly 278 minutes. It stars Jack Holt as Jack Holt/Nick Farrell and Evelyn Brent as Kay Drew, Agent R49, with Tristram Coffin, C. Montague Shaw, and a supporting ensemble filling out the criminal network and law-enforcement team. Narration by Knox Manning frames the action and lends the production a breath of documentary-like authority: the Secret Service, it announces, is charged with two vital responsibilities — protecting the President and safeguarding the nation’s currency. That opening assertion places the serial squarely within a civic and wartime imagination of law and order while allowing the plot to unfurl as a dramatic contest between institutional guardians and organized counterfeiters.

It is useful to begin by acknowledging a critical point: the serial is not a film noir movie, historically distinct and formally defined by postwar existential dread, chiaroscuro cinematography, and morally ambiguous protagonists. Nevertheless, this serial traffics in some of the aesthetic and thematic concerns that noir criticism values — urban (and quasi-urban) corruption, trapped characters, fatalistic plotting, and recurrent imagery of pursuit and entrapment. The critic will use "film noir movie" as a comparative lens throughout this piece to illuminate what Holt of the Secret Service borrows from and diverges away from the darker tradition.

Production Background and Historical Context

Holt of the Secret Service was the 16th serial released by Columbia Pictures and was produced by Larry Darmour. James W. Horne, the director, had made his name with brisk, dynamic staging and a lightness of touch that often lent even perilous set pieces a propulsive rhythm. The screenplay credits include Basil Dickey, George H. Plympton (credited as George Plympton), and Wyndham Gittens; cinematography was by James S. Brown Jr., and editing was shared by Dwight Caldwell and Earl Turner. Lee Zahler contributed the music, rounding out a studio team that knew how to make serial material move at speed.

Released on November 21, 1941, the serial arrived at a moment when audiences sought both reassurance and spectacle. Columbia marketed it as a special attraction and dispatched sales personnel to screen sample chapters to exhibitors, an indication that the studio invested in the project’s exhibition prospects. Contemporary trade journals praised the serial’s “suspense, action, and production,” noting that there was “something doing every minute” in the first installments. Critics of the period observed that the serial might appeal to both adults and younger viewers because of its relentless action.

Jack Holt’s participation in the serial is notable. A star of long standing at Columbia, Holt had been perceived as demoted to serials after a clash with studio boss Harry Cohn. The casting nevertheless carried box-office weight: Holt's presence anchored the serial in a masculine, steady authority that the series needed given its episodic jeopardy, and Evelyn Brent’s casting provided a counterbalance to the tough-guy archetype with a women’s agent role that refused to be pigeonholed. The critic notes that Columbia characterized this serial for an adult audience, with Darmour’s production intended to be thrilling and logically constructed rather than simply sensational.

Plot and Chapter-one Commentary: "Chaotic Creek"

The first chapter, Chaotic Creek, plunges immediately into the serial’s central crime: a gang of counterfeiters has kidnapped John Severn (played by Ray Parsons), the U.S. Treasury Department's most accomplished engraver. The criminals intend to coerce Severn into producing plates for virtually undetectable counterfeit money. That premise supplies the serial’s ticking clock: keep the plates out of the crooks’ hands, keep Severn alive long enough to learn who runs the ring, and prevent the distribution of counterfeit currency.

From the opening narration — which declares that the Secret Service stands “between the Chief Executive and an assassin’s bullet, but between the nation’s currency and the vicious criminals who would despoil it” — the serial stakes out a moral horizon: the agents are frontline defenders. The serial’s action begins with a pursuit that is both kinetic and expository. A car chase, gunfire, an injured prisoner, and the urgency of medical intervention all occur within minutes. The scene work in Chaotic Creek is brisk, situationally dense, and exemplary of serial storytelling: exposition is delivered through incident rather than long speeches, and characters are defined by how they act under pressure.

The critic highlights a crucial strategy of the Secret Service agents in chapter one: infiltration by masquerade. Jack Holt’s agent impersonates Nick Farrell, an escaped convict of reputation, a gambit designed to secure entry into the gang’s hideout. His partner Kay Drew, a woman operative, will play his companion in the ruse. The choice to make Kay an operative — not a damsel in distress — is a productive divergence from certain genre expectations. She is introduced to the chief and briefed on the danger; the briefing sets the tone for the serial’s mix of procedural detail and pulpy danger. "A slight mistake may cost you your life," a superior warns; Kay replies, "I'm used to that," a line that signals her hardened competence.

In the hideout, Severn is coerced, beaten, and placed before the press. The criminal head, Lucky Arnold (John Ward), hides behind henchmen such as Quist (Ted Adams) and Ed Valden (Tristram Coffin), a classic arrangement that allows the boss to remain insulated from direct exposure. The gang boasts an unblinking will to violence: their purpose is purely utilitarian — make money indistinguishable from national currency and distribute it through maritime and racing networks. Here the serial touches on what the critic calls suburban noir: crime that is organized, manufactured, and rationalized for profit rather than existential rebellion.

Scene-by-Scene Close Reading

One of the earliest sequences finds Severn in peril. He defies his captors and proclaims his patriotism: "You can't make me turn traitor to my country." The gang retorts that they have "means" to extract cooperation, promising brutal persuasion if necessary. The critic emphasizes how this exchange anchors the serial in clear moral dualities: heroes who believe in institutional duty and villains who rationalize coercion as business. The simplicity of the moral argument is not a flaw; rather it allows the serial to mobilize suspense around practical obstacles — can Holt protect Severn, cripple the operation, and seize the plates?

The infiltration plan hinges on subterfuge: the Secret Service fabricates an escape rumor about Nick Farrell, plants their agent Jack Holt as Farrell, and relies upon the gang’s desire to recruit experienced criminals. Jack Holt’s impersonation functions as a double-take on masculinity: the hero performs toughness, but the performance is strategic. Kay Drew poses as the agent’s wife to complete the masquerade. The critic notes how this pairing prefigures serial bromances and obligatory faux-marital roles that make the ruse credible and animate interpersonal banter — sometimes comic, sometimes terse, always useful for exposition.

When the police nearly derail the plan by arresting the wrong men, the serial demonstrates its appetite for improvisation. Sequences of prison infirmary visits, staged certificates, and narrow escapes are all deployed to sustain tension and to showcase how thinly the heroes’ cover is stretched. The script advances through reversed expectations: Haley’s Law would call for neat policing, but the serial values friction and near-misses because they prolong suspense across chapters.

Cast, Performance, and Character Dynamics

Jack Holt’s casting as the principal Secret Service agent is a deliberate studio choice: his screen persona had long been associated with rugged, dependable heroism. Holt’s Nick Farrell is calibrated to convey toughness with a wry undercurrent; his character’s faux-escapee persona requires him to display bravado and guile in equal measure. The critic admires Holt’s capacity to play the straight man in peril while allowing the serial’s stunts and set pieces to be the public spectacle.

Evelyn Brent as Kay Drew functions as a gendered counterpoint: she is an operative, not a passive accessory. Contemporary observers — Variety among them — found this casting surprising, noting that Brent did not fit the demure stock type usually assigned to serial female leads. The critic views Brent’s presence as one of the serial’s strengths: she performs agency, confronts danger, and participates materially in the plot’s mechanics. Kay Drew’s insistence on doing her duty, and her practical comments about being "used to that" where danger is common, give her an arresting presence and help the serial resist reductive gender roles.

Tristram Coffin’s Ed Valden serves as an energetic midlevel antagonist; John Ward’s Lucky Arnold is the corporate face of criminality — careful, profit-minded, and layered with strategic caution. Ted Adams’ Quist provides henchman competence while Ray Parsons as John Severn gives the moral beating heart of the first episodes — a craftsman coerced into complicity, whose conscience and technique anchor the counterfeit operation’s danger. The critic finds these casting choices effective: they converge into a unit that allows each episode to stage a series of confrontations without losing narrative clarity.

Direction, Pacing, and Serial Mechanics

James W. Horne’s direction privileges momentum. The critic notes the film’s breakneck pace and heavy reliance on cliffhanger devices — the serial architecture that divides the story into escalating crises designed to ensure audience return. Each chapter strings together set pieces: a car chase, a narrow escape, a staged breakout, or the reveal of a concealed villian. Horne’s prior work in comedy equipped him to stage six-against-one fight sequences and complex action tableaux with an economy of movement that keeps the eye busy without sacrificing coherence.

The editor’s role is crucial. Dwight Caldwell and Earl Turner balance short takes and cross-cutting that ratchet up urgency. Scene durations are short; exposition is frequently compacted into a single, efficient exchange. The critic compares this economy with how a film noir movie often uses tight, focused exchanges to reveal character under duress. In the serial, these moments occur with far more frequency, but the logic is similar: a terse line can reveal motive, risk, or strategy.

Music by Lee Zahler amplifies peril and triumph in a classical studio idiom. The score’s cues are cueing devices rather than leitmotifs of deep psychological import; they punctuate rather than interpret. In the serial format, music marks beats and underscores danger in the same way a title card might, and this functional use of music supports the serial’s forward motion.

Stylistic Affinities with Noir and Divergences

It is important to be precise: Holt of the Secret Service is not a film noir movie in form. It lacks the high-contrast chiaroscuro cinematography, the femme fatale archetype rooted in moral ambiguity, and the postwar existential malaise that typify noir. Yet the serial shares with noir a fascination with crime as an organizing logic for narrative — not merely incidental, but systemic. Counterfeiting, in this storyline, is a modernized crime: it is technical, industry-like, and bound up with networks that cross borders via gambling ships and distant islands. The critic regards this as a proto-noir concern: a recognition that modern crime operates through systems and professionals.

Several motifs align with noir sensibilities. The sense of entrapment — both physical and moral — pervades the serial. Severn’s forced labor on the plates is an instance of the craftsman corrupted by coercion, a variation on the noir theme of the ordinary person plunged into criminal currents. The recurring imagery of pursuit, surveillance, and deception provides a noir-adjacent texture. That said, serials like Holt pursue a clear moral resolution; the hero’s virtue will be vindicated, and the villain’s designs unmasked. In a film noir movie, moral lines are frequently blurred; here they remain bright.

The critic emphasizes that using the phrase film noir movie throughout the analysis sharpens the contrast: repeated invocation of the phrase "film noir movie" highlights where the serial departs from that more introspective, shadowed tradition and where it sometimes converges on similar themes (crime as industry, entrapment, moral hazard). This approach helps readers recognize that classic serials and film noir movies are not wholly separate lineages but overlapping currents in American cinema history.

Episode Structure and Chapter Titles

Holt of the Secret Service spans 15 episodes. The chapter titles outline a program of escalating peril: Chaotic Creek; Ramparts of Revenge; Illicit Wealth; Menaced by Fate; Exits to Terror; Deadly Doom; Out of the Past; Escape to Peril; Sealed in Silence; Named to Die; Ominous Warnings; The Stolen Signal; Prison of Jeopardy; Afire Afloat; Yielded Hostage. The critic appreciates how each title performs two functions: it promises immediate jeopardy and it contributes to an arc wherein each subsequent peril feels both novel and consistent with the serial’s logic of constant threat.

This structural design is a key reason serials like this function as episodic prime-time entertainment long before television’s serial rhythms were standardized. The serial keeps viewers engaged by blending local closure (a fight won, a narrow escape) with persistent, unsolved problems (the plates remain a threat). The rhythm seen across chapters resembles the beat-driven nature of a film noir movie’s scenes of investigation, but remade for sustained weekly return rather than a single sitting.

Marketing, Reception, and Box-Office Impact

Columbia Pictures marketed the serial as a special attraction. The studio’s sales executive, M. J. Weisfeldt, undertook a regional screening tour to stimulate exhibitor interest; trade journals reviewed sample chapters favorably. The Exhibitor commented that the first two chapters were "a good one from the standpoints of suspense, action, and production," and Motion Picture Daily predicted the serial would have broad appeal. Critics paid attention to the casting of Evelyn Brent, whom Variety thought unconventional for the demure type usually found in serial romances; this divergence garnered attention and discussion — an unintentional marketing angle.

The serial proved successful in theaters, with Jack Holt’s name attracting an audience that associated him with action and adventure. The critic notes that the serial’s commercial success reinforces an important point about classics: historical worth is not always a measure of artistic pretension but often of the capacity to engage contemporaneous audiences and to shape future expectations of genre film. In that sense, Holt of the Secret Service functioned well within its era and, as with many effective serials, gained a long tail of interest from collectors and later film historians.

Legacy: From Theaters to Home Video and Scholarship

After the serial’s copyright lapsed in 1969, Holt of the Secret Service became one of the few Columbia cliffhangers available for modern assessment. Scholars and aficionados have praised the serial for its breakneck pace and expertly staged fight sequences — a legacy traced back to James W. Horne’s economy as a director. The serial has been described as something of a poster child for Columbia’s serial output, particularly in assessments that became possible only when more titles circulated on home video and public archives.

The critic underscores that Holt’s serial manages to function as both a time capsule and a durable piece of action storytelling. Its set pieces — the marina escape, the gambling ship sequences, confrontations in remote hideouts — remain pedagogically useful for students of staging and rhythm. For those who research serials as precursors to the modern franchise, the serial’s model of escalating jeopardy and serialized resolution offers a clear line toward today’s episodic high-stakes storytelling.

Preservation, Availability, and Viewing Recommendations

Holt of the Secret Service is now among the Columbia serials available for contemporary viewing: it can be found in archival repositories and often appears on public-domain platforms that host classic film and serial material. The critic recommends viewing the episodes with attention to both macro-structure (how the fifteen-chapter architecture distributes peril) and micro-textures (how a single scene compresses exposition, impetus, and fight choreography). Watching the first chapter, Chaotic Creek, yields a strong sense of the serial’s tonal commitments: a civic-heroic framing that legitimizes the hero’s actions, combined with quick-witted ruses and pragmatic heroics that advance the plot.

For viewers interested in a noir-adjacent lens, the critic suggests attending to the serial’s depiction of the counterfeiters as industrial criminals and to the scenes of infiltration that create constant ambiguity about identity — an agent pretending to be a criminal engages with the noir concern of performance and identity. Yet one should watch alert to the serial’s fundamental differences from a film noir movie: it promises restitution and triumph rather than unresolved moral ambiguity.

Themes and Interpretive Notes

Several themes demand attention.

- Institutional Sovereignty vs. Private Criminal Industry: The plot sets the Secret Service against an organized counterfeit ring, framing national security as a matter of technical mastery (how money is printed) as much as policing. The critic reads this as an example of how mid-century cinema dramatized technological competencies as strategic capital.

- Performative Masculinity and Undercover Work: Holt’s impersonation of Nick Farrell foregrounds questions of performance and credibility. The ruse requires simulated toughness; the hero’s ability to enact criminal identity for the state’s ends complicates the simple hero/villain binary, albeit in a way the serial ultimately resolves in favor of the law.

- Female Agency within Pulp Narrative: Kay Drew’s role as Agent R49 challenges the soft-minded female stereotype. The critic views her as a proto-action heroine whose competence anticipates later serial heroines and mid-century screen figures who could both argue policy and wield a gun.

- Serial Ethics: The serial invests viewers in procedural ingenuity: how to delay the press, how to misdirect the gang, how to maintain cover. These ethical—and tactical—concerns create a drama of means rather than a drama of metaphysics.

Interpreting these themes side-by-side with the sensibilities of a film noir movie sharpens critical distinctions: noir tends to emphasize internal moral collapse and atmospheric disillusion, whereas Holt of the Secret Service privileges external obstacles and eventual institutional triumph. Nevertheless, the serial’s emphasis on surveillance, identity, and the corrosive power of money as motive nods toward noir concerns even as it remains a fundamentally different emotional project.

Why Film History Should Care

Serials like Holt of the Secret Service are often sidelined in film histories that privilege features. Yet the critic argues they deserve careful attention because they represent a dominant form of American popular narrative in the studio era: serialized, economical, stunt-driven, and oriented to audience return. The serial’s craftsmanship in staging and economy in storytelling illuminate how momentum can be engineered without sacrificing clarity. For historians of genre, the serial provides evidence that the grammar of suspense was shared across formats and that many techniques later associated with the film noir movie and the modern thriller were honed in serial production workshops.

Holt of the Secret Service also offers a useful case study in star-management and studio politics. Jack Holt’s assignment to serial work after conflict with a studio head, and Evelyn Brent’s casting against expectations, show how the studio system shuffled talent and how those shifts could produce compelling work. The critic notes that audience response validated Columbia’s choices: the serial’s popularity demonstrates how reputation and content synergized to sustain theatrical revenue and critical attention.

Conclusion: A Serial for the Serious Fan and the Curious Student

Holt of the Secret Service provides a sustained entertainment that rewards both casual viewing and rigorous analysis. It is not a film noir movie in the classical sense, but it often touches on similar thematic territory: identity under pressure, the manufacturing of crime, and the politics of surveillance. The serial’s virtues lie in its dramatic pacing, its robust action choreography, and its cast’s disciplined performances. James W. Horne’s direction converts serialized constraints into a strength, turning chapter endings and recurring jeopardy into a pleasurable engine of audience anticipation.

For collectors, historians, and cinephiles, the serial is recommended viewing. Those who approach it as a historical document will find much to admire: the clarity of design, the economy of characterization, and the studio craft on display. For readers interested in the crossover between serials and darker cinematic traditions, the serial functions as a reminder that American cinema in the early 1940s circulated a range of narrative strategies that later crystalized into formal genres like the film noir movie.

Finally, the critic invites readers to seek out Holt of the Secret Service in archival collections and streaming repositories, to watch Chaotic Creek and subsequent chapters with an eye for how the serial composes suspense, builds character through action, and stages moral clarity in an era of global uncertainty. For those who subscribe to a channel or archive that curates classic cinema, Holt provides both instruction and entertainment: a primer in serialized peril and a reminder that, before noir and the modern thriller set many of their terms, studio serials taught audiences the pleasures of episodic danger.

Recommended Viewing Guide

- Begin with chapter 1, Chaotic Creek; note how exposition is integrated into action.

- Observe Kay Drew’s agency across chapters 1–4 to track a female operative’s role in serial drama.

- Watch the ship and island sequences (mid-to-late chapters) for staging of escape and jurisdictional maneuvering.

- Compare sequences of pursuit and entrapment with classic film noir movie scenes to discern stylistic differences and thematic overlaps.

Holt of the Secret Service remains a spirited artifact of its time: a serialized, tactical, and theatrically effective example of how studio cinema engineered suspense to secure audiences week after week. The critic encourages the historically minded viewer and the aficionado of crime narratives to explore it — ideally, with patience for the serial form and curiosity about the antecedents of modern genre storytelling.