In the restored presentation of The Rogues' Tavern, directed by Robert F. Hill and released in 1936, a compact, claustrophobic mystery unfolds that both reflects its Poverty Row origins and hints at the visual and thematic currents that would later define the film noir movie. Produced by Sam Katzman for Mercury Pictures and distributed by Puritan Pictures, the film is a tight 70‑minute murder melodrama that assembles a small cast—Wallace Ford, Barbara Pepper, Joan Woodbury, Clara Kimball Young—and a single, storm‑lashed location into a study of paranoia, false identities, and revenge.

Outline

- Introduction and production context

- Synopsis and structural anatomy of the plot

- Key performances and casting choices

- Direction, cinematography, and production design

- Genre placement: murder mystery, B‑picture, and the film noir movie connection

- Themes, motifs, and narrative devices

- Legacy, reception, and why the film remains interesting

- Conclusion and viewing recommendations

Introduction and Production Context

The Rogues' Tavern belongs to the productive but often overlooked tier of 1930s American cinema sometimes labeled as Poverty Row output. Mercury Pictures Corporation produced the film with Sam Katzman as producer; the screenplay is credited to Al Martin, while Robert F. Hill handled direction and William Hyer was responsible for cinematography. Released on June 4, 1936, the film runs approximately 70 minutes, a common length for economical studio fare intended to play as part of a double bill.

This economy of means is essential to the film’s character. The single setting—a remote, firelit inn called the Red Rock Tavern—functions like a theatrical stage, concentrating action and character in a pressure cooker. The Rogues' Tavern is, by design, efficient and focused: it stages a series of murders, suspects, and revelations that move briskly toward the solution. Within that efficiency lies the film’s charm and the seeds of a darker sensibility. It is precisely in the way it stages shadow, suspicion, and moral ambiguity that one can read an early echo of what would later be labeled the film noir movie.

Synopsis: Anatomy of a Closed‑Room Mystery

The narrative begins on a bleak and windy night when Jimmy Kelly (Wallace Ford) and Marjorie Burns (Barbara Pepper) arrive at the Red Rock Tavern hoping to be married immediately. They are forced to wait for a justice of the peace who has been wired to meet them. Soon, other guests arrive after receiving similar summonses—Harrison, Hughes, Mason, and Gloria Roloff (Joan Woodbury), among others—establishing the central mystery: why have these apparently unrelated people been brought together in this isolated location?

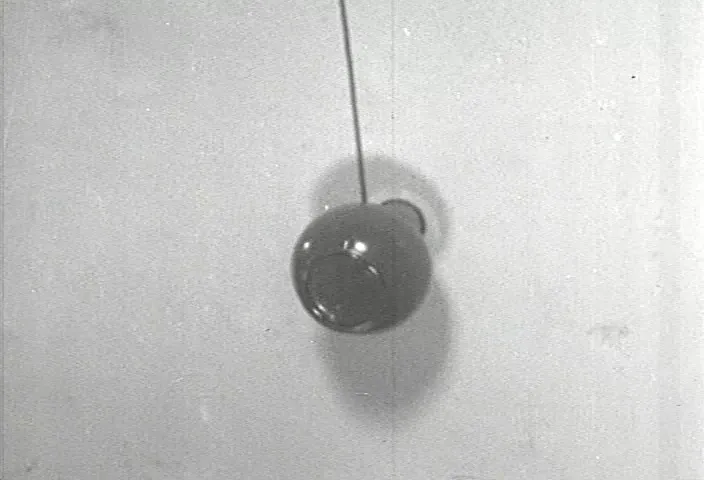

Events escalate quickly. Harrison is discovered dead in his room, apparently the victim of a savage animal attack; later, Hughes dies in a similar fashion. Telephone lines are found cut, doors are barred, and windows are locked, creating a locked‑room scenario where escape is impossible and suspicion multiplies. Jimmy, periodically revealed to be more than a mere guest—he is a detective—begins investigating. He discovers a startling physical clue: a false dog's tooth, used to fake an animal attack. The murders are thus staged to mislead, and the human culprit at work is deliberately playing on everyone’s fear of a wild beast.

As the story unfolds, marital plans, confessions, and a macabre dénouement follow. Mrs. Jamison (Clara Kimball Young), the tavern’s proprietress, and her apparently invalid husband (Mr. Jamison) become focal points of suspicion. A twist arrives when Jamieson—wheelchair bound—confesses to the murders. Yet the presence of a lurking figure in the cellar, an inventor named Morgan, and a revelation of jewel smuggling among certain guests complicate what seemed a tidy confession. The true motive—vindication, revenge, and old deceit—emerges in a final confrontation that tests the moral center of the film.

Cast and Performances: Economy and Character Work

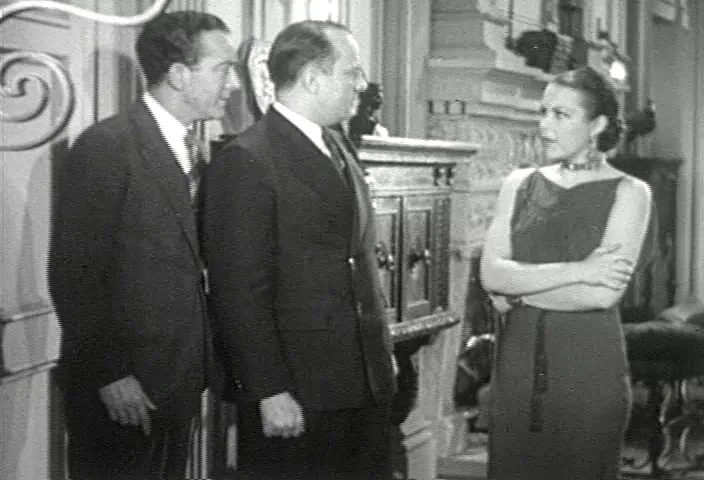

The Rogues' Tavern assembles a roster of actors who, in a matter of minutes onscreen, must sketch their personas and motives convincingly. Wallace Ford’s Jimmy Kelly anchors the film as both viewer proxy and practical problem‑solver. Ford’s performance is deceptively casual: his affable demeanor masks professional competence, a useful contrast in a film that asks the audience to trust a central sleuth amidst a tangle of deceit.

Barbara Pepper’s Marjorie Burns is both romantic lead—an engaged woman eager to be married—and an active investigator, rummaging through luggage and making discoveries that propel the mystery forward. Pepper gives Marjorie a combination of practical grit and nervous vulnerability that suits the story’s high stakes: she is both the vulnerable fiancee and an agent of detection.

Joan Woodbury’s Gloria Roloff and Clara Kimball Young’s Mrs. Jamison represent two poles of feminine presence in the tavern. Woodbury’s Gloria is exoticized by the script (a Mexico City origin is mentioned), and the role capitalizes on Woodbury’s quicksilver charm. Clara Kimball Young, a star of earlier decades, brings a weathered dignity to Mrs. Jamison; her presence grants the production a touch of theatrical gravity. John Elliott as Mr. Jamison, the apparently helpless invalid, performs the most surprising physical shifts in the film when his frailty is revealed to be partly false—a crucial plot turn.

Supporting Players and Uncredited Depth

Secondary players—Jack Mulhall as Bill, Ivo Henderson as Harrison, Ed Cassidy as Mason, and John Cowell as Hughes—populate the narrative with plausible motives and human brittleness. The inclusion of a trained animal (Silver Wolf) as "Silver Wolf" in the credits echoes the film’s use of the dog as misdirection. Each actor contributes to the pressure cooker environment: an unremarkable scene of guests at a tavern table becomes volatile as secrets leak.

Direction, Cinematography, and Production Design

Robert F. Hill directs with a steady hand practiced in economical storytelling. There is little flourish, but much purposeful blocking: the tavern’s rooms are arranged like puzzle pieces, and the camera often frames figures against the hearth or the barred windows—visual anchors that reinforce themes of confinement and dread. William Hyer’s cinematography is functional but effective. Lighting emphasizes the fire’s glow and the encroaching darkness, using contrast to heighten anxiety rather than cinematic spectacle.

The production design—modest because of budget constraints—uses repeated motifs: locked doors, barred windows, the telephone with severed wires, and a conspicuous chest of luggage. The set is theatrical, not realistic, but this artificiality benefits the film. It keeps attention on character dynamics and the riddle of motive. The tavern becomes a laboratory for human behavior under duress: where budgets limit spectacle, the screenplay and staging intensify psychological pressure.

Plot Mechanics and Narrative Devices

Al Martin’s screenplay builds the mystery through a cascade of questions: Who sent the wires summoning each guest? Why are doors barred and windows locked? Are the victims killed by a wild dog, or is someone cleverly mimicking such an attack? The script favors revelation through discovery: physical clues (the dog’s tooth), contrivances (the severed telephone lines), and human admissions (Jamieson’s confession). These devices serve both to conceal the murderer and to implicate the viewer in the investigative process.

One striking device is the false confession. The confession functions on multiple levels: it is a red herring for the audience, a moral beat that reveals character strength and weakness, and a commentary on guilt and protection. Jamieson’s admission—if accepted at face value—would resolve the mystery quickly. But the presence of other clues and motives forces Jimmy and the audience to suspect that the confession is only a piece of a more complex puzzle. This attention to misdirection aligns the film with many classic detective tales: the truth is layered and must be peeled away carefully.

Genre Placement: Murder Mystery, B‑Picture, and the Film Noir Movie Connection

The Rogues' Tavern is first and foremost a murder mystery—a closed‑circle thriller where motive, means, and opportunity are distributed among a small group of characters. As a 1936 B‑picture, its economic constraints shape the narrative economy and the film’s stagebound aesthetics. Yet there are aspects of tone, mood, and moral ambiguity that invite a broader categorization. When modern critics search for antecedents of the film noir movie, they will find resonant elements here: the smoky atmosphere, the play of shadows, the entrapment of characters, the theme of guilt and revenge, and the morally ambivalent resolution.

It is important to temper labels. The Rogues' Tavern predates the codified noir era of the 1940s and 1950s, and it lacks many defining noir features (the urban nightscape, the hardboiled antihero, the femme fatale driven to transactional sin). However, as a genetic ancestor or cousin, the film shares certain sensibilities. The film noir movie is often characterized by a mood of disillusionment, misleading surfaces, and the idea that ordinary spaces—hotels, streets, taverns—mask deadly intentions. The Rogues' Tavern situates all these dynamics within a single room, making it an instructive example of how noirish atmosphere could be achieved without the later era’s visual gloss.

To label the film a film noir movie strictly would be anachronistic. Yet to appreciate it as part of noir’s extended family is to recognize how B‑cinema experimented with themes and atmospheres that would later be amplified by larger studios, different lighting approaches, and more complex moral frameworks. The Rogues' Tavern, by staging paranoia and staging betrayal, anticipates noir’s fascination with the breakdown of social contracts and the destructiveness of secrets.

Themes, Motifs, and Recurring Imagery

Several recurring motifs structure the film’s meaning: confinement, deception, and retribution. The tavern itself is a motif of confinement: barred windows and locked doors reduce the characters’ world to a single stage. Deception operates on many registers: forged communications that summon guests, false physical evidence (dog teeth), and feigned disabilities. These deceptions are not merely plot devices but thematic statements on how appearances can be weaponized.

Retribution is the film’s moral engine. The final reveal ties several threads into a unified motivation: revenge for an earlier injustice. The backstory involving Helen Armstrong—a wronged woman whose fate triggers an extended desire for vengeance—situates the killings as the culmination of a long, private malice. Revenge in The Rogues' Tavern is not cathartic; it is corrosive, turning ordinary domestic spaces into crime scenes and implicating the innocent and the guilty alike. This moral ambiguity—where blame is layered and justice is provisional—reinforces the film’s kinship with noir sensibilities.

Symbolic Objects: The Dog, The Telephone, The Luggage

Certain props carry symbolic weight. The false dog’s tooth is a grotesque emblem of misdirection; it literalizes the idea of faking a monstrous outside threat to conceal human malice. The severed telephone line symbolizes modernity made impotent—technology that should connect becomes a tool for isolation. Luggage, repeatedly searched by Marjorie and Mrs. Jamison, becomes a container of secrets: jewels, lies, and stolen identities are hidden in suitcases, a domestic metaphor for the hidden sins of adults on the run.

Technical Notes: Sound, Editing, and Pacing

The Rogues' Tavern’s audio design is of its time: dialog‑heavy, with sound effects used sparingly for atmospheric punctuation. The scene where a recorded voice or phonograph is used to terrorize the guests in the cellar is a clever exploitation of sound to manipulate panic—an economical trick that stages offscreen menace without elaborate special effects.

Editor Dan Milner manages the film’s pace with an eye to tightening suspense. Cuts are placed to sustain tension during interrogations and to let audiences absorb clues during quieter moments. The speed with which the film moves from one clue to the next suits the B‑picture form; there is little fat, and the narrative rarely lingers on purely expository passages. This briskness keeps the film lean and engaging, even if it sometimes glosses over psychological depth in favor of forward momentum.

The Film’s Moral Economy and the Question of Guilt

One of the film’s most interesting aspects is its treatment of confession and culpability. Jamieson’s confession reads as both protective and performative. He shoulders guilt with the voice of an old man who might be protecting someone else. But the screenplay refuses to let confession be the last word. The existence of an inventor lurking in the cellar and the final revelation of motivations tied to Helen Armstrong complicate the moral ledger. The film asks whether legal guilt is the same as moral guilt, and whether a single admission can resolve a labyrinth of deceit. In doing so, it avoids comforting reductiveness. The ending suggests that the legal system, the social order, and human conscience all operate on different terms—a question the later film noir movie would explore with greater cynicism.

Comparative Notes: The Rogues’ Tavern Among Its Peers

As an example of mid‑1930s low‑budget crime cinema, The Rogues' Tavern sits comfortably beside other closed‑space mysteries and “old dark house” thrillers. It shares affinities with films that trap assorted guests in a single locale and expose their secrets under stress. What sets The Rogues' Tavern apart is its combination of domestic detail with a surprisingly vindictive core: a revenge motive seeded in past injustice rather than opportunistic greed. This moral fixation gives the film a seriousness that exceeds its running time and budget.

Viewed through the prism of the film noir movie tradition, one can see how these B‑pictures supplied narrative and atmospheric experiments for the later genre. They explored the vocabulary of darkness, suspicion, and moral collapse in compact forms—ideas that would later be expanded by bigger budgets, stronger studio backing, and a post‑war world eager for darker stories.

Legacy, Reception, and Why the Film Still Matters

The Rogues' Tavern has not been canonized as a classic, but it remains a fascinating artifact of its moment. Its merits include a lean, effective mystery chassis, a set of performances that make much of spare material, and a thematic preoccupation with deception and revenge that feels modern even today. For students of genre history, the film is valuable because it demonstrates how economical filmmaking can craft convincing suspense and moral perplexity without extravagance.

Critically, the film is often appreciated by aficionados of early talkies and B‑movie historians. As a compact narrative, it demonstrates the strengths of Poverty Row production—ingenuity, briskness, and a willingness to embrace darker themes. For viewers curious about where the film noir movie sensibility first gestated, The Rogues' Tavern is worthy of attention. It provides an early example of how shadows and secrets can be staged on a small scale to create a palpable sense of dread.

Viewing Recommendations and Practicalities

At roughly 70 minutes, The Rogues' Tavern is an ideal specimen for an evening of classic film study. Viewers interested in the genealogy of noir should watch the film looking for atmospheric cues—the interplay of light and dark, the prevalence of confinement, and the moral ambiguity of confession. Those who prefer pure mystery should focus on the screenplay’s puzzle mechanics: the way physical evidence is used to mislead and the timing of revelations.

Because the film is compact, it rewards repeated viewings. The first watch reveals the plot’s broad strokes; subsequent viewings allow the patient viewer to trace small details—the placement of props, the underplayed glances of secondary players, the way sound is used to heighten offscreen menace. For lovers of classic cinema, this economy of detail is satisfying: it is the sort of film that was made quickly but thought through carefully.

Final Assessment: An Early Echo of the Film Noir Movie

The Rogues' Tavern is not a film noir movie in the strict historical sense. It predates the era of noir and lacks many of the genre’s codified characteristics. Nonetheless, its stylistic and thematic choices—confinement, misdirection, revenge, moral ambiguity, and a persistent sense of urban‑adjacent dread—make it an important artifact for anyone interested in the evolution of noir aesthetics within American cinema.

Robert F. Hill’s direction and Al Martin’s script combine to make a minor classic of efficient suspense: a film that uses limited resources to produce maximum tension and to stage an exploration of the corrosive effects of lies and retribution. The Rogues' Tavern rewards those who encounter it not as a historical oddity but as a working example of how mid‑century American filmmakers, even on tight budgets, experimented with the language of shadow and suspicion that would later be more famously articulated in the film noir movie.

Why Classic Film Lovers Should Revisit This Work

For the student of cinema, The Rogues' Tavern offers several compelling takeaways:

- It demonstrates how limited settings can intensify narrative focus, a lesson in economical storytelling.

- It provides an early example of atmospherics that would later be canonized in noir cinema—dim lighting, moral ambiguity, and a landscape of secrets.

- It showcases character work by reliable actors who convey a surprising range within a short running time.

- It serves as a historical document from Poverty Row, illuminating how resourceful studios produced genre content for mass audiences.

These elements make The Rogues' Tavern more than a curiosity; they make it a useful text for understanding how genre, economics, and creative problem‑solving intersected in 1930s Hollywood. And for those tracing the lineage of the film noir movie, it offers a faint but persistent echo of the darker cinema that would follow.

Concluding Thoughts

Ultimately, The Rogues' Tavern is a compact, effective murder mystery that earns its place among the more interesting B‑pictures of the mid‑1930s. While the film does not claim to be a major studio opus, it exemplifies the ingenuity of filmmakers working within constraints—and in doing so, it gives contemporary viewers a window into the early narrative and atmospheric experiments that would later inform the film noir movie.

For classic cinema critics and fans alike, the film is worth revisiting: it is a reminder that sometimes the most intriguing creative work happens when filmmakers have to get clever, fast, and economical. The Rogues' Tavern offers claustrophobic tension, a cache of misdirection, and a moral ambiguity that lingers after the lights go up—qualities that make it a small but resonant piece of American film history.