The 1954 thriller Suddenly, directed by Lewis Allen and anchored by Frank Sinatra's unnerving performance as John Baron, is a lean, relentless film that sits comfortably within the canon of classic crime pictures. This examination considers Suddenly as a film noir movie — a tightly wound psychological drama that transforms a tranquil small town into a pressure cooker of menace and moral decision. Drawing on the film itself and contemporary accounts, the piece treats Suddenly both as a product of its era and as an enduring exercise in tension, character study, and moral complication.

Outline

- Introduction: positioning Suddenly as a film noir movie

- Historical and production background

- Detailed plot anatomy with attention to key scenes

- Character and performance analysis, especially Sinatra and Hayden

- Themes: violence, dislocation, patriotism, and ordinariness invaded

- Directorial and technical choices that make it a film noir movie

- Contemporary reception and longer‑term influence

- Conclusion and the film's place in classic cinema

Introduction: framing Suddenly as a film noir movie

Suddenly arrives as a small‑scale, high‑intensity example of cinematic noir stripped to essentials: a single setting, a ticking clock, and a ruthless antagonist who forces ordinary citizens into impossible choices. It is proper to call Suddenly a film noir movie because it shares core noir traits — moral ambiguity, a pervasive sense of threat, character types haunted by war experience, and a visual economy that amplifies psychological pressure. The following analysis treats Suddenly as both crime melodrama and archetypal noir, tracing how the film converts a domestic interior into a battlefield and interrogates the social aftermath of violence.

Background and production

Suddenly is based on Richard Sale's short story "Active Duty" (1943) and adapted by Sale into a tight screenplay. Produced by Robert Bassler under Libra Productions and released by United Artists in October 1954, Suddenly runs a brisk seventy‑five to eighty‑two minutes depending on sources. The film's skeleton of a plot — assassins renting a perch to kill a visiting president — springs from contemporary anxieties. Writer Richard Sale conceived the story after reading about President Dwight D. Eisenhower's presidential visits by train to Palm Springs. That germ of idea — a nation’s highest office placed suddenly within reach — makes Suddenly a political thriller as much as a personal catastrophe for the Benson family.

Cinematographer Charles G. Clarke and editor John F. Schreyer impart a lean, efficient visual style. David Raksin's music underlines tension without sentimental excess. Frank Sinatra, cast against the previous type that made him a matinée idol, was employed as a "heavy" for the first time; Sterling Hayden, James Gleason, Nancy Gates, and a supporting ensemble provide steady foil performances. Production locations were deliberately modest: exteriors were shot in Saugus, a California town whose station and ridge provide the film's required geography.

Plot anatomy: compression, escalation, and the spectral intruder

The film opens as quietly as a postcard from small‑town America. A passing driver asks a police officer for directions to Three Rivers; he learns he is in Suddenly, "Suddenly what?" The verbal exchange — a tiny joke about a town once so wild that events occurred "suddenly" — registers as an ironic prologue. Suddenly’s narrative compresses time and action into a single afternoon. The president's train will stop at five o'clock; the film measures the prelude to that moment and the moral tests it forces upon the Benson household.

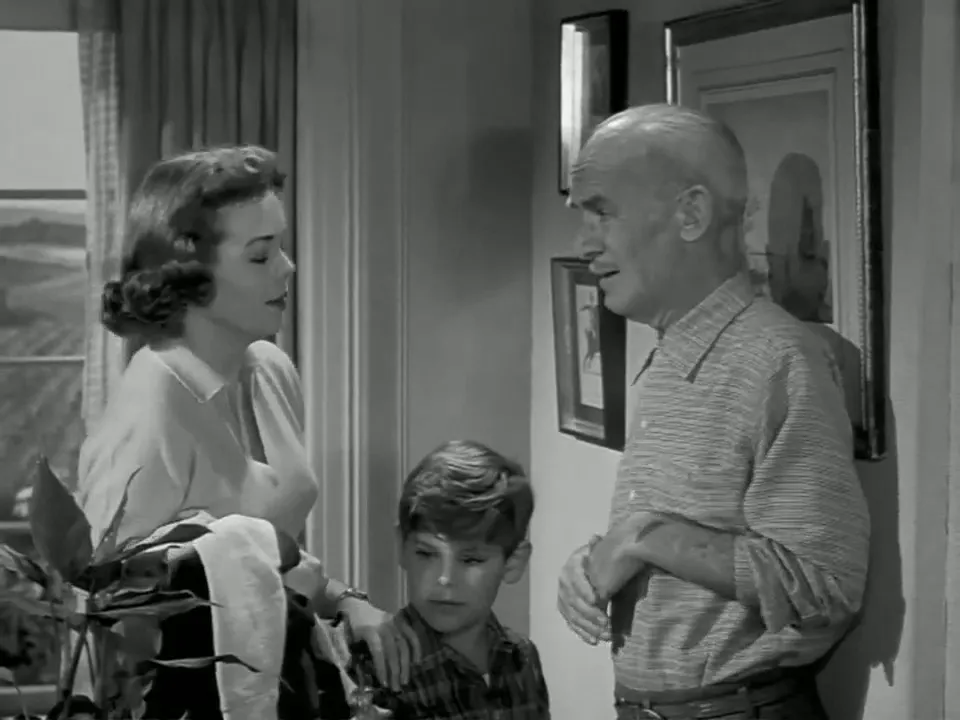

The Benson house sits atop a hill with unobstructed sightlines to the station. Ellen Benson (Nancy Gates), her son "Pidge" (Kim Charney), and her father‑in‑law "Pop" Benson (James Gleason) form a compact, protective family unit. Pop is a retired Secret Service man; his presence lends an ironic intimacy to the intruders’ choice of target. Into this domestic geometry stride men who claim to be agents checking security but are, in truth, assassins.

In a neat inversion of small‑town trust, John Baron (Frank Sinatra) and his henchmen — Benny, Bart, and Wheeler among them — present themselves as official personnel checking on the president's arrival. They bundle the family into a single confined drama: the Benson household becomes both a prison and the perfect sniper’s nest. Baron’s methods are clinical: he commands the room, explains his motives and displacements, and immediately neutralizes resistance. He murders Dan Carney (Willis Bouchey), the Secret Service chief who arrives to coordinate security, and wounds Sheriff Tod Shaw (Sterling Hayden), who arrives to check on the house. These actions inaugurate the moral center of the film.

Baron is a professional in the most inhuman sense. He reveals why he is there: he is paid, half up front, to kill the president. He insists he has nothing personal against the president; money is the motive. Yet the script gives depth to his character by making him simultaneously a veteran and a psychopath, a man shaped by war and by tastes for violence. Baron declares he earned a Silver Star, an admission that becomes part confession, part boast. The film stages the paradox that men can be both rewarded for sanctioned killing in war and punished or scorned for violence in peace.

Sheriff Shaw, as local law enforcement and moral touchstone, represents the proposition that duty and law persist amid extremity. Shaw's arm is broken; he is bandaged and sent to the bedroom, but his presence — his implacable, relatively quiet courage — helps to anchor the film’s tension. Pop Benson plays a veteran’s role in reverse: he feigns heart trouble and orchestrates a plan that turns the household’s broken television set into an instrument to foil the assassination. This choice — the use of domestic technology as a weapon against the invaders — is one of the film's sly ironies and a display of noir resourcefulness.

The assassins fix the rifle to a metal table and affix the apparatus to the window overlooking the tracks. The montage of the rifle, the drilled holes, and the makeshift tripod conveys the mechanized, impersonal nature of the impending murder. Jud, the TV repairman (James O'Hara), is compelled to enter the household and "fix" the set, a plot necessity that becomes the instrument of fate: under the guise of repair, Jud connects a plate output to the table's metal legs. Pop purposely pours water under the table, hoping a touch to the metal will electrocute the sniper. The plan, however, misfires: one of the henchmen, not Baron, touches the table first and is electrocuted, firing the rifle reflexively and causing the train to speed past without stopping. The chaos culminates in Baron's death: Ellen seizes the chance and shoots him, and the sheriff fires a final, fatal shot.

The aftermath reveals casualties and moral scars: Jud dies, the sheriff is wounded but functional, and the town has been violently altered. Sheriff Shaw asks Ellen to meet him at church the next day, a final gesture of normalcy trying to reassert itself after catastrophe. The film closes on the same motif that introduced it — a driver asks the way to Three Rivers and learns he is in Suddenly — but the final exchange is weighted differently. The small joke on the town’s name now carries an ambivalent note: everything in Suddenly changed "suddenly," and the residents will never again be identical to their previous selves.

Characters and performances: Sinatra’s menace, Hayden’s steadiness

Frank Sinatra’s John Baron is a career pivot. Sinatra — until then frequently cast as a romantic lead or sympathetic soldier — embraces an antiheroic, menacing persona in Suddenly. The role demands a precise calibration of charm, menace, and unblinking cruelty. Contemporary critics recognized the risk and praised Sinatra’s work; Bosley Crowther singled out Sinatra’s "melodramatic tour de force." Sinatra's Baron is matter‑of‑fact about his vocation: he is paid to kill. The speech in which he describes his wartime experience and his Silver Star blends boast with rationalization, offering no political ideology, only a transactional logic. Sinatra’s voice — conversational, deceptively casual — becomes the film’s central instrument of dread.

Sterling Hayden’s Sheriff Tod Shaw provides the human counterweight. Shaw is a man accustomed to boundaries and law; he cannot be bribed into capitulating to cynical violence, and his steadiness persists even after being wounded. Hayden’s performance is economical; he is less showy than Sinatra but proves effective as the moral backbone. James Gleason’s Pop Benson offers a different kind of performance: avuncular, world‑weary, and resourceful. Gleason threads comedy and cunning; Pop’s retired‑agent backstory explains his competence in the household’s defense.

Nancy Gates embodies Ellen Benson’s trauma and courage. Ellen is a widow guarding her child; her arc traces from fear to decisive action. The moment she shoots Baron is morally messy: the audience must reconcile sympathy for self‑defense with the gravity of killing. The script places that choice squarely upon Ellen, forcing the film to dramatize the cost of violence even as it endorses survival.

Casting as noir strategy

The casting itself is noir‑inflected: Sintra’s charisma makes him unusually effective as a villain, a technique noir often employs—using attractive or charismatic actors to blur boundaries between charm and danger. The presence of an ordinary household head like Pop Benson, given a secret past as a protective agent, fits noir’s interest in revealed histories and private pasts that collide with the present.

Themes: violence, war residues, normality violated

Suddenly concerns itself with the rupture of ordinary life. Norton’s filmic logic is simple: bring political violence up close, and watch how ordinary people respond. The assassination attempt — an event of national magnitude — becomes an intimate domestic catastrophe, and the film asks how citizens and local institutions respond when national security is suddenly present in a small living room.

One key theme is the residue of war. Several characters, including Baron and Pop, are veterans. Their wartime experiences color their attitudes toward killing. Baron's confessions (the Silver Star, the "chopping" he performed) are presented not as patriotic valor but as evidence of his psychological dislocation. The film implies that wartime conditioning and postwar economies of violence can produce fragmented moralities. This is not a pacifist tract; the film repeatedly positions violence as sometimes necessary and sometimes corrupting, but it refuses sentimental resolution. In that sense, Suddenly functions as a film noir movie by interrogating the moral and emotional fallout of combat and the ambiguous place of violence in a democratic society.

Another theme is the banality of complicity. In the conspirators’ dialogue, there is a candid financialism: the assassination is a business deal. The men rationalize it with hedged language about identification, escape plans, and half‑payments. The film’s political subtext — that treason can be outsourced to mercenaries — is bleak. Yet the film is also careful to dramatize individual responsibility: the sheriff refuses to make bargains that endanger citizens, Ellen refuses to cower eternally, and Pop uses his knowledge to attempt rescue. The moral calculus remains unsettled; the audience is made to live inside the gut decisions that ordinary people must make.

Directorial and technical choices that make it a film noir movie

Director Lewis Allen stages violence with a discipline that favors tension over spectacle. The film’s running time forces compression: there are no gratuitous subplots, no scenic detours. Allen uses staging and camera geometry to trap characters within frames, turning rooms into crucibles. The sniper, the fixed rifle, and the drilled table are visual motifs of mechanized killing; close framing of faces, low‑key lighting, and the use of the hilltop vantage point create a claustrophobic atmosphere even in exterior shots.

Charles G. Clarke’s black‑and‑white photography contributes to the film’s noir identity. Contrast is sharp where necessary, and grey tonalities are used to accent domestic textures: wallpaper, a kitchen table, a radio set. The lighting renders faces as psychological landscapes—Sinatra’s face in half‑shadow, Gleason’s lines into maps of experience. Editing preserves suspense: time is measured by clocks and the honk of a far‑off train, and cuts are used to escalate the stakes in synchrony with the schedule of the president's approach.

Sound design and Raksin’s score are spare. Dialogue carries the weight of exposition and character. The film resists melodramatic crescendos until the sudden violence at its climax. This restraint amplifies the film’s moral seriousness: Suddenly does not revel in violence; it dissects it.

Domestic technology as plot engine

The film’s inventive use of the television set as a sabotaged tool is a noirish inversion: an item meant to mediate entertainment becomes an instrument of death or salvation. Pop’s knowledge of television circuitry—his ability to turn 5,000 volts into a potential weapon—turns domesticity into battlefield. That the plan kills the wrong man adds tragic irony: schemes intended to secure life can misfire and increase harm. That miscalculation is a noir staple: plans rarely execute with the clarity their authors imagine.

Reception at release and critical afterlife

Suddenly was well‑received upon release. Bosley Crowther praised the film’s direction and acting and singled out Sinatra for a "melodramatic tour de force." Variety and Newsweek similarly commended Sinatra’s performance and the film’s tight construction. Over time film scholars have placed Suddenly within noir discussions: Carl Mazek argued that the film’s "Machiavellian attitude" links it with the more brutal, amoral ends of 1950s noir, such as The Big Night and Kiss Me Deadly. The film’s contemporary Rotten Tomatoes score is notable: a 100% approval rating based on a limited set of reviews (nine in aggregate), with an average rating suggesting steady critical appreciation.

Suddenly has also accrued a controversial afterlife. Sinatra reportedly sought the film withdrawn from circulation after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy because of rumors that Lee Harvey Oswald may have seen it prior to his act; Sinatra's alleged attempt to buy and destroy prints is part of Hollywood lore, though the story is disputed and partly apocryphal. The film later entered the public domain because its copyright was not renewed, making it widely accessible. The film has been colorized and reissued in various home video forms, and in 2018 Serge Bromberg produced a restoration from the camera negative for Lobster Films.

Influence and connections: from Suddenly to The Manchurian Candidate

The film’s conceptual kinship with later Cold War paranoid narratives is evident. In 1959 Richard Condon published The Manchurian Candidate, whose later film adaptation in 1962 shares thematic DNA with Suddenly: a psychologically damaged hero, political assassination plots, and the weaponized subjectivity of former soldiers. Notably, Sinatra participated in the later film (as a producer and actor), and Paul Frees, who appears in Suddenly, served as the narrator of The Manchurian Candidate. The narrative lineage suggests that Suddenly contributed to an emergent set of postwar anxieties about cold‑war sabotage and the ease with which national institutions could be subverted.

Suddenly's spectacle is less about showmanship and more about moral anatomy. For this reason, the film influenced filmmakers who saw the efficacy of a small budget and a focused, intense script. The idea that a national catastrophe can be staged in one house underlines the film's continuing relevance: political violence is conceivable even in the most seemingly secure domestic spaces.

Why Suddenly remains a compelling film noir movie

Three features underline Suddenly’s endurance as a film noir movie. First, its compression of time and place intensifies moral choices. The single‑afternoon arc keeps the audience inside the family’s emotional rhythm and makes the resulting decisions more immediate. Second, Sinatra’s John Baron is calibrated to be both charisma and monstrousness, a noir favorite: the man who charms his way into catastrophe. Third, the film refuses easy moral closure. Even after the assassination attempt fails, the town is forever altered; the violence cannot be unlearned.

The film’s technical economy also contributes: a lean script by Richard Sale, focused direction by Lewis Allen, and tight editing leave little room for fat, producing a film where every frame matters. The black‑and‑white palette and careful sound design maintain a noir mood without resorting to overwrought stylistic flourishes. In essence, Suddenly treats noir as a moral form rather than merely an aesthetic: it is less about mood and more about the backstage mechanics of violence and survival.

Key sequences analyzed

The arrival of the "agents"

The impostors’ arrival is staged as politely official: a resident welcomes them, the men produce credentials (or the semblance of credentials), and they assert authority. The film makes use of the small domestic rituals — conversation about church attendance, chit‑chat about groceries — to make the invasion feel ordinary at first, which heightens the eventual betrayal. This sequence exemplifies how sudden appearances can be normalized in small towns; the ease of entry is disturbingly plausible.

The bolting of the rifle

The technical work to bolt the rifle to the table is given meticulous attention. The conspirators plan a three‑second window to kill the president and leave. The film’s camera lingers over bolts, drills, and metal legs as if the mise‑en‑scène itself were complicit in the act. This sequence functions as both procedural detail and thematic symbol: modern violence is engineered, not romantic. The quiet mechanicality also contributes to the film’s dread: death is not always theatrical; it is often the result of simple, methodical preparation.

The television gambit and misapplied justice

Pop Benson’s plan to electrify the table reveals the film’s moral ambiguity. Pop is not a professional assassin; he is a retired agent and a grandfather who improvises. The attempt to use domestic technology against the invaders is resourceful and ironic, but it also underscores noir’s fatalism: even well‑intentioned schemes can fail and produce collateral loss. The electricity sequence kills a henchman, sets off the alarm, and precipitates chaotic violence that leaves Jud dead. The film does not sanitize the outcome. Instead, it forces the audience to reckon with the messy consequences of self‑defense and improvisational resistance.

Reception, box office, and later critical standing

Financially the film performed modestly, with box office receipts around $1.4 million. Contemporary responses were generous, particularly to performance choices and Allen's direction. The film's contemporary Rotten Tomatoes rating suggests a sustained critical appreciation. Moreover, film scholars have used Suddenly to discuss the darker strains of 1950s American cinema—where domestic safety becomes fragile and the veteran's return to civilian life yields psychological discontinuities that threaten the social order.

The film's place in repertory programs and film study syllabi rests on its compactness and clarity. It is also useful as a study in staging political crisis at a human scale. As such, Suddenly can be recommended to viewers who seek a concise film that dramatizes postwar anxieties without extraneous spectacle.

Legacy, controversies, and restorations

The film’s public domain status widened its availability, but paradoxically contributed to a patchwork of prints and varying image quality. Colorized versions emerged in the 1980s and later, and a 2018 restoration by Serge Bromberg brought clarity to a camera negative rarely seen in its original condition for decades. The controversy surrounding Sinatra's alleged attempts to withdraw the film after Kennedy's assassination remains part of Suddenly’s mythology. Whether or not Sinatra successfully attempted to suppress the film, the rumor signals how culturally volatile the film’s subject matter appears when historic events unfold.

Suddenly also has a lineage in later political thrillers, as the film's generator of tension — the near miss of presidential assassination — resonates with other narratives that ask what happens when national events are staged locally. The film's influence on The Manchurian Candidate is indirect but visible: both works harness the figure of the returned soldier and the possibility of political assassination staged from within America's interior.

Conclusion: Suddenly’s durable power as a film noir movie

Suddenly is a compact, disciplined film that proves how much intensity filmmakers can squeeze into a short running time. It is properly called a film noir movie because it combines mood, moral ambivalence, and a focus on violent intrusion into domestic life. The film’s strengths include Sinatra’s uncomfortably charismatic villainy, Sterling Hayden’s grounded sheriff, James Gleason’s wily Pop, and a screenplay that keeps the story taut and purposeful. Lewis Allen’s direction creates a world with airtight tension and spare but effective cinematic means.

As a piece of postwar American cinema, Suddenly captures the era’s anxieties: the ease with which violence can be privatized, the brittle moral orders that returnees to civilian life confront, and the ways ordinary people improvise under pressure. The film remains a model of how to stage national stakes in a domestic space and how to present moral complexity without didacticism. For students of noir and classic cinema, Suddenly offers an exemplary lesson: atmosphere, character, and a relentless commitment to the consequences of violence make for a film that endures.

Further viewing and context

Those interested in Suddenly's historical and thematic contemporaries might pair it with other mid‑century noirs that treat small towns as sites of menace or that explore returning veterans' psychological scars. Comparisons with The Manchurian Candidate reveal thematic echoes across a decade of Cold War cinema. For a study in minimalism, Suddenly sits beside other lean thrillers that use a constrained set and clocklike narrative to escalate tension.

Appendix: notable lines and memorable moments

- Opening exchange about the town's name—an ironic prologue to the film’s theme of sudden disruption.

- Baron’s parade of wartime memories and the Silver Star confession—sinister self‑justification.

- The bolt‑and‑drill montage—mechanical preparations for political murder.

- Pop’s television gambit—domestic technology redirected into desperate resistance.

- Ellen’s final shot—moral closure that is necessary but still ambiguous.

Suddenly remains a succinct masterclass in how to stage a political thriller at the level of a household. It is a film noir movie that trades in moral fog rather than visual flamboyance, and it succeeds by refusing to reassure its audience. The town of Suddenly is forever changed, and so is anyone who watches the film with an eye for the costs of confronting sudden violence.