The Great St. Louis Bank Robbery (also titled The St. Louis Bank Robbery in its opening credits), directed by Charles Guggenheim and John Stix and released in 1959, stands as a compact, unsparing specimen of crime cinema. Framed and staged with an eye for documentary precision, it reads in equal parts as a procedural heist picture and a domestic tragedy, and it can be profitably examined as a film noir movie whose moral tension is as much about character psychology as about the mechanics of a botched robbery. This critic examines the film through the lenses of production history, performance, narrative architecture and visual style, showing how this modest United Artists release functions as a film noir movie anchored by Steve McQueen’s uneasy magnetism and by the frankness of on-location reenactments.

Outline: What the Critic Will Cover

- Background and production: how a real 1953 bank attempt in St. Louis became a film

- Plot and structure: the meticulous plan and the fatal missteps

- Character studies: George Fowler, John Egan, Gino, Willie, and Ann

- Performance analysis, with special focus on Steve McQueen

- Stylistic and noir elements: moral ambiguity, fatalism, urban realisms

- Use of documentary technique and local participants

- Critical reception, legacy, and why it remains of interest to noir-minded viewers

- Concluding assessment: filmic value and cultural footprint

Background and Production: From Real Crime to Celluloid

The Great St. Louis Bank Robbery is rooted in a true event: a 1953 attempted robbery of Southwest Bank in St. Louis. The film was shot on location in 1958, employing an uncommon mix of professional actors (led by a young Steve McQueen) and St. Louis residents, including men and women from the municipal police department and bank employees who reenacted their real roles in the sequence of the crime.

The film’s production values are intentionally modest. Produced by Charles Guggenheim under the banner Charles Guggenheim & Associates and distributed by United Artists, the picture runs 89 minutes and was released in the United States on September 10, 1959. Beyond its economical runtime, the production’s documentary impulse gives it an arresting immediacy: the crowd, the storefront details, the bank floor—these are not stylized reproductions but the texture of the place itself. That documentary impulse makes this a film noir movie that trades some of noir’s expressionist glamour for a more clinical, forensic fidelity to circumstance.

The principal creative team listed on the available record credits Charles Guggenheim and John Stix as directors and Richard T. Heffron as the writer. Victor Duncan served as cinematographer, Warren Adams edited the film, and Bernardo Segall provided the score. The cast combined theatrical performers—Crahan Denton as John Egan, David Clarke as Gino, and others—with Steve McQueen portraying George Fowler, the young man recruited as the getaway driver.

Plot and Structure: A Tight, Tragic Heist

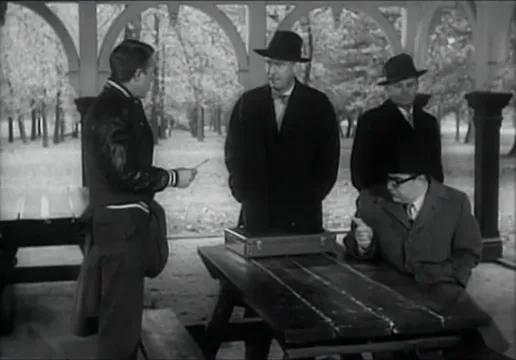

On the surface the film presents a straightforward blueprint of criminal enterprise: a seasoned but bitter mastermind, John Egan; a hardened sidekick, Willy; a frightened ex-con, Gino; and a naive-lapsed collegian, George Fowler, who is recruited to drive the escape car. Their plan is painstakingly assembled—casing the Southwest Bank, gathering schedules, timing traffic lights, rehearsing the getaway—until a single human intervention and a technical miscalculation collapse the entire scheme.

The narrative is economical. The early scenes sketch the gang’s hierarchy and tradecraft. Egan insists on discipline—no women, no loose talk—while he treats George with a complicated mixture of condescension and paternal interest. They study the bank for days: who walks in, where the switchboard is, where patrol cars tend to appear. A well-laid plan, logically executed, is supposed to yield a brief window of two minutes to take as much as possible and leave. The plan’s premise—that multiple alarms in an urban bank are often false—reflects the film’s procedural realism.

But the narrative’s focus is not only on the mechanics of crime; it is on the psychological unraveling that follows. When Ann, Gino’s sister and George’s former love, sees George and intervenes, she writes a warning on the bank window: a line in lipstick that reads, in effect, “Warning—you will be robbed.” That single act converts the robbery from a technical operation into a personal catastrophe. Egan’s fury—already bred by a lifetime of misanthropy—finds a human target, and in a macabre escalation he throws Ann to her death from a fire escape. The act reshapes the robbery into a story of guilt, betrayal and a moral reckoning for George. As such, the film becomes less merely a heist picture and more of a film noir movie in the classical sense: it is a tale of inexorable consequence in which personal weakness and fate conspire to destroy the protagonists.

Characters and Performances: The Souls Behind the Plan

The ensemble is compact but distinct, and the film treats each role with an economy that clarifies motives without excess exposition. This casting and the performances form one of the film’s primary strengths and its noir credentials.

George Fowler — the reluctant wheelman

Steve McQueen’s George Fowler is the emotional center. Fowler is a former collegiate athlete, a young man with no criminal past who is recruited by Gino and reluctantly drawn into the plan because he needs to borrow money from Ann and is promised a chance to get his life back on track. McQueen’s performance is one of restrained intensity—an economical embodiment of a character who is at once proud and vulnerable, trying to reclaim his former life yet pulled into violence by association and circumstance. As the robbery collapses, Fowler’s postures and inflections betray an adolescent terror that gives the film its tragic core. This kind of portrait anchors the film’s claim to function as a film noir movie: a seemingly ordinary man pulled into moral darkness, not by original depravity but by cumulative compromises and betrayals.

John Egan — the hard-bitten mastermind

Crahan Denton’s John Egan is a grim, controlling force who combines meticulous planning with a volatile temperament. He insists on rules—no women, quiet obedience—and yet his past informs his cruelty. In a revealing confession, Egan divulges that he murdered his abusive mother by pushing her down a flight of stairs. That disclosure is more than a salacious detail; it explains a misogyny and a brutality that will culminate in Ann’s murder. Egan’s arc—meticulous, misogynistic, ultimately self-destructive—exemplifies noir’s fascination with damaged heroes who are their own worst enemies, and Denton delivers the steely menace of such a figure without theatrical excess.

Gino and Willy — the compromises of loyalty

David Clarke’s Gino is the anxious intermediary: an ex-con terrified of prison who is trying to scrounge together money for his trial. He inhabits an equivocal moral space—both vulnerable and culpable. Willy, the longtime minion (James Dukas), is a co-conspirator who longs to retire with Egan but also embodies the ordinary brutality of the criminal milieu. Their interactions—bickering, loyalty testing, scapegoating—play out with a weary realism that situates the film more in the territory of social drama than melodrama. The dialog often reads like an account of small men beating themselves up over bad decisions, which is a familiar noir motif.

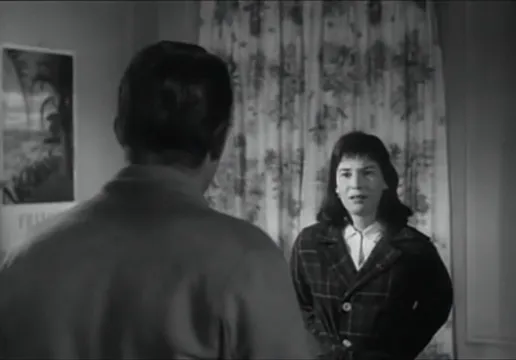

Ann — the warning and the human cost

Molly McCarthy’s Ann is both a moral anchor and a tragic casualty. Her act—writing a warning on the bank window—transforms the route of the story. She does not call the police, but she cannot remain passive. Her action marks a rupture in the gang’s confidence, and Egan’s subsequent response is both cruel and final. The film does not sentimentalize Ann; she is neither idealized nor merely instrumental. Her presence illuminates the emotional stakes and brings into focus the film’s noir thesis: ordinary human compassion can provoke fatal, fatalistic violence in unscrupulous hands.

Steve McQueen: A Magnetic Presence

By the time of release, Steve McQueen was emerging into national recognition through television, and his role here has the hallmarks of the screen persona that would define his career: a laconic, restless intensity, physical economy and a gaze that suggests both vulnerability and menace. McQueen’s George is young and buffeted by forces he cannot control—financial need, misplaced loyalty, and the wrath of a man who has nothing to lose. That precarious position gives McQueen room to be quietly explosive. His performance anchors the film’s emotional logic and ensures that it reads effectively as a film noir movie because the moral unraveling is located in a character who is identifiable and sympathetic up to the point where he is broken.

Stylistic Elements and the Film Noir Label

The Great St. Louis Bank Robbery can be argued to be a film noir movie in temperament, if not always in aesthetics. Classical film noir is often associated with high-contrast lighting, brooding shadows and expressionist camerawork. This picture, by contrast, emphasizes verisimilitude: bright exteriors, routine interiors, and a camera that records rather than stylizes. Yet its thematic DNA—nihilism, fatalism, moral ambiguity, the downfall of an ostensibly ordinary protagonist—maps directly onto the noir tradition.

There are several features that justify labeling this picture as a film noir movie:

- Protagonist as antihero: George Fowler is an ordinary man ensnared by circumstance.

- Moral ambiguity: loyalties shift and “right” choice is often unavailable.

- Fatalistic trajectory: the plot is structured as a descent, with a single act (Ann’s warning) precipitating collapse.

- Psychological motivation: Egan’s confession and actions are rooted in traumatic history rather than mere greed.

- Urban realisms: the city, the bank, the streets are treated as determinative spaces in which destiny unfolds.

In short, while the film may lack the stylized chiaroscuro of some noirs, it is firmly within the family of film noir movie narratives because it trades on the genre’s thematic insistence that crime is not merely an external act but an internal corruption that leads to inevitable collapse.

Documentary Technique and On-location Realism

One of the film’s most striking features is its blend of dramatic reconstruction with documentary elements. The filmmakers shot on location in St. Louis and recruited local participants—bank staff, police officers, even residents—for the reenactments. That approach lends authenticity to domestic scenes and to the robbery sequence itself. When the alarm sounds and the precinct radios crackle, it feels like a genuine civic panic, not a studio affectation. The inclusion of actual St. Louis police and employees adds a civic verisimilitude and complicates the film’s ethics: the real people who lived the event are depicted alongside actors, and the film thus becomes, in part, a civic document.

This technique also affects tone. The film avoids theatrical glamor; instead, it renders the robbery as an almost bureaucratic operation—timetables, radio checks, traffic counts. That clinical approach enhances the film’s insistence that criminality can be methodical and yet it soon collapses into irrational violence. The documentary precision accentuates the tragedy: when ordinary, routinized criminal procedure yields to human frenzy, the result is all the more devastating.

Thematic Concerns: Masculinity, Mistakes, and Moral Accounting

Several themes recur and merit examination.

Masculinity and authority

John Egan’s leadership depends on a coercive masculinity: he demands strict discipline and punishes failure. His tirades against women and his confession about the murder of his mother form a vicious logic: female presence, in Egan’s mind, invites disorder and guilt. It is an ugly, archaic logic that the film exposes as both delusional and destructive. Ann’s presence—human, humane—disrupts the machismo order, and the result is fatal. The film thereby interrogates a certain toxic masculinity that seeks to obliterate ambiguity by brutal force, making it a film noir movie that critiques as much as it dramatizes male violence.

The moral cost of small compromises

George Fowler’s descent is gentle at first: a favor, a borrowed dollar, a hope to go back to school. But incremental compromises accumulate and put him in the position of being accountable for actions he did not initially plan to commit. The film’s moral calculus is not theatricalized by grand metaphysics; rather it is grounded in the ordinary arithmetic of choices and consequences. That makes the picture a film noir movie that insists the banal often produces the catastrophic.

Fatalism and the non-spectacular catastrophe

Unlike some heist pictures that linger on clever plotting or the thrill of execution, this film centers the anticlimactic fallout. At first the plan seems plausible; then the oversight (no scanner tuned to police channels, a relocated switchboard, an unexpected witness) collapses it. Noir often traffics in romantic fatalism—fate conspires against the protagonist. Here, fate is less metaphysical than contingently cruel: the world’s small administrative shifts—where a switchboard sits, when a patrol car drives by—determine the protagonists’ doom. The film is thus a film noir movie whose fatalism is rooted in civic contingency rather than poetic destiny.

The Bank Sequence: Where Procedure Meets Panic

The robbery sequence is the film’s centerpiece. The gang rehearses timing—the two-minute window, the timing of traffic lights, the cadence of patrols. Their plan is precise: mask up, get the switchboard operator away from her post, line the customers up with their backs to the robbers, and take as much from the tills as possible before alarms bring the police. The rehearsal scenes—watching a traffic light’s red phase and timing a getaway down Magnolia—evoke a mechanical coldness.

But the sequence also shows how illusions of control can crumble quickly. A silent alarm is triggered; the gang did not bring a police scanner and thus lacks situational awareness; a busier-than-expected presence of police on the street complicates their escape routes. Willy flees, Egan panics and lashes out, and the robbery becomes a chaotic tableau of human fear. The film stages this collapse without melodrama: people shout, someone is shot; the camera observes the disintegration with a restrained directness. This sober rendering reinforces the film noir movie’s ethos: the genre’s moral admonition that crime, even when technically executed, invites personal disintegration.

Violence and Moral Reckoning

The film’s most shocking moment—the murder of Ann—is not shown as an ornament of style but as an abrupt, humanly ugly consequence: Egan throws her from the fire escape. This scene reframes everything: the robbery is no longer a professional exercise but a personal catastrophe. The audience then sees how guilt and violence infect the group. Gino dies by suicide in the basement vault; Egan storms out with a teller as a human shield and is shot down by police; George, wounded, takes a hostage and then, in a moment of clarity, releases her and surrenders. The endings are not tidy; each character’s fate is grim and consequential. The film noir movie here functions as an ethical adjunct: crime is not glamorous and the human cost is literal and irreversible.

Reception and Legacy

Contemporary reviews were mixed. A New York Post review described the film as “fairly lucid” and praised its dramatic plot and documentary format, noting a competent script and an enlivening score. The Los Angeles Citizen-News, however, saw the film as a “garbled attempt at arty realism” that rehashed old heist material. These divergent responses reflect the film’s hybrid identity: it is neither a polished studio noir nor a straight documentary; it is a hybrid experiment in realist dramatization, which makes it interesting to critics and viewers who favor genre that leans toward authenticity.

Today, the film remains notable for several reasons. It captures an early, lean Steve McQueen performance that hints at the star persona he would soon fully inhabit. It preserves on film an actual civic event, with local participants who reenacted their own experiences. It situates a small-time crime narrative within a social fabric, and thus offers an instructive case study in how noir themes—fatalism, masculine violence, and the consequences of moral compromise—can be rendered without the lush stylization of studio melodrama. For scholars and enthusiasts of classic crime cinema, it represents a hybrid artifact: a film noir movie that reaches for documentary truth.

Historical Base and Ethical Considerations

The film is based on the real attempted robbery led by Fred William Bowerman, whose actions inspired the fictional John Egan. The decision to include actual police personnel and bank employees raises ethical questions about representation. On the one hand, the reenactments add authenticity; on the other, they complicate the film’s status as a moral object: the people participating are reenacting trauma for the sake of a dramatized product. The filmmakers treated this material with a certain sobriety—the result is more clinical than exploitive—but the ethical dimension remains. The film noir movie label thereby extends beyond aesthetics and into the realm of civic responsibility: how does one dramatize criminality without reinforcing sensationalist impulses? This film largely answers by stripping aesthetic ornamentation in favor of documentary restraint.

Why It Matters: The Film as Teaching Tool

For students of genre and for viewers who live in the intersection of docudrama and classic crime, The Great St. Louis Bank Robbery offers pedagogical value. It shows how a modest production can make formal choices that emphasize authenticity over melodrama, and it demonstrates the continuing vitality of noir themes even when stripped of glamorous lighting and sweeping jazz scores. The film is a film noir movie that foregrounds the small determinisms of civic life—switchboards moved, patrol car rhythms, lipstick warnings—and teaches how such apparently incidental details can shape destinies. That lesson is precisely why the film continues to be a subject of critical interest.

Technical Notes: Cinematography, Editing, and Score

The film’s technical crew—Victor Duncan’s cinematography, Warren Adams’ editing, and Bernardo Segall’s music—combine to produce a lean, focused cinematic object. The camera work favors documentary clarity: wide frames that capture movement, close registers that catch facial micro-expressions, and camera positions that emphasize civic space over dramatic angles. Editing is brisk; the film clocks in under ninety minutes and gives little room for narrative flab. Segall’s score, cited by critics as enlivening, supports the action without overwhelming it, underlining tension and emotional notes with discreet dramatic cues. Together, these elements help the film function as a film noir movie stripped of expressionist ornamentation but retaining moral intensity.

Comparative Notes: Where It Sits in Noir Cinema

The Great St. Louis Bank Robbery does not fit neatly into an orthodox category, and that is part of its fascination. It lacks the femme fatale archetype and the chiaroscuro lighting that define many noirs, but its fatalism, moral ambiguity and the antiheroic fallibility of its lead establish clear kinship. It relates to other heist-driven noirs—where careful planning meets messy human choices—and it also anticipates later crime films that emphasized realism over romanticization.

Viewed as a film noir movie, it is a variant rather than a purist example. It shows how noir’s central theme—how ordinary men get swallowed by moral failure—can be rendered by different cinematic languages, including documentary-influenced realism. For modern viewers and students of noir, the picture is a reminder that noir is less a set of visual signatures than a thematic constellation: when stories insist that crime corrodes the soul and destroys ordinary lives, they function as noir regardless of stylistic trappings.

Key Scenes and Quotable Lines

Several scenes deserve special attention for their craft and thematic clarity. The planning meeting—where Egan draws the map, times traffic lights and insists on the “no women” rule—establishes the moral architecture of the group. Ann’s nighttime visit to the bank, where she writes the lipstick warning, is a small, decisive human act that precipitates disaster. The robbery’s panic sequence and Egan’s murderous leap from the fire escape are the film’s most dramatic moments, executed without spectacle yet devastating in impact.

There are also lines that linger. Egan’s admonition, “No women,” is not merely operational; it is a credo that explains his character. George’s later protests—“I’m not a thief” and then “I’m not going back”—are poignant refrains that mark his unspooling. Ann’s grief and George’s surrender at the end show the human cost of small decisions. The film’s dialog is rarely florid; its power arises from plainspoken statements that acquire resonance through events.

Conclusion: The Film’s Place in the Canon and the Value of Reexamination

The Great St. Louis Bank Robbery is not a grand classic in the way some studio noirs are, but it is an important artifact: an early Steve McQueen vehicle, a documentary-inflected dramatization of a real crime, and an austere meditation on how ordinary people’s choices and civic contingencies produce catastrophe. It is a film noir movie by temperament and theme if not by high-contrast aesthetics, and it rewards viewers interested in how noir motifs can be translated into realist terms.

For critics and cinephiles who probe the genre’s limits, the film offers an instructive contrast: noir need not be glamorous to be profound. It can be a sober civic portrait of how small decisions amplify into irreversible consequences. The film’s moral clarity—crime does not pay, and human compassion can become a trigger for unimaginable violence—remains unadorned and unnervingly direct. That is the film’s enduring power. As a film noir movie it reminds the viewer that the genre’s core is ethical gravity, and no matter the stylistic mode, ethical gravity can make a modest picture memorable.

Recommendations for Viewing

- Watch with attention to the film’s documentary choices: the presence of local police and bank staff gives the robbery sequence a particular texture.

- Observe Steve McQueen’s performance for the early development of his screen persona—reserved, physical, and morally fraught.

- Note how small civic details (a switchboard moved, the layout of the bank, a timed traffic light) control the story’s outcome—this is where the film transforms into a film noir movie of contingency.

- Consider the ethical implications of reenacting a real crime with local participants; the film is as much a civic document as a dramatic artifact.

In sum, The Great St. Louis Bank Robbery deserves attention not as a polished exemplar of classical noir aesthetics but as a sober, morally urgent film noir movie. It asks difficult questions about responsibility, masculinity, and how ordinary moments—timing, surveillance lapses, a woman’s act of conscience—can precipitate ruin. For those interested in the transmutation of true crime into cinema, and in the ways noir themes persist across forms, this film remains a compact, rewarding study.

Selected Credits (for reference)

- Directed by: Charles Guggenheim, John Stix

- Written by: Richard T. Heffron

- Produced by: Charles Guggenheim

- Starring: Steve McQueen (George Fowler), Crahan Denton (John Egan), David Clarke (Gino)

- Cinematography: Victor Duncan

- Edited by: Warren Adams

- Music by: Bernardo Segall

- Production company: Charles Guggenheim & Associates

- Distributed by: United Artists

- Release date: September 10, 1959 (U.S.)

- Running time: 89 minutes

For viewers and students of classic crime cinema, The Great St. Louis Bank Robbery is a reminder that noir’s heart often beats quietly beneath procedural surfaces. As a film noir movie, it asks that viewers listen to its small, staccato beats—the timing of a traffic light, the whisper of a radio dispatch, the tremor in a young man’s voice—and recognize how such details accumulate into irrevocable consequence.