This article examines The Hitch-Hiker (1953) in the spirit of a classic cinema critic: close, unsparing, and attentive to craft. The piece opens by acknowledging Ida Lupino—the director, co-writer, and an industry pioneer—and places the film squarely within the context of the genre debates and cultural resonance that surround any remembered film noir movie. Drawing on the film’s production history, its factual basis, and the film’s own dialogue and beats, the critic unpacks how Lupino and her collaborators turned a headline-making crime into a taut, spare piece of cinema that remains both unnerving and instructive for lovers of the film noir movie.

The Hitch-Hiker is often discussed in cinephile circles as a compact, high-tension example of a film that maximizes a small cast, austere settings, and the relentless psychology of a single villain. As a film noir movie, it strips the genre down to essentials: moral peril, chiaroscuro implication, claustrophobic travel, and the collapse of ordinary men under extraordinary pressure. This article will analyze the film’s themes, the choices Lupino made as director and writer, its performances, and the technical elements—cinematography, editing, and sound design—that together define the film as a ferocious film noir movie.

Outline

- Introduction: Ida Lupino, the film and its status as a film noir movie

- Historical and production context

- Plot overview and key scenes

- Directing and writing: Lupino’s hand

- Performances: Talman, O’Brien, Lovejoy

- Cinematography, editing and sound: austerity and tension

- Real-life source material and ethical adaptation

- Scene-by-scene critical commentary (selected sequences)

- Reception, legacy, and preservation

- Conclusion: why this film endures as a film noir movie

Historical and Production Context

The Hitch-Hiker arrived in 1953 as a distinctive, low-budget film that nevertheless carried the weight of topical horror. Directed by Ida Lupino and produced by Collier Young, the film was made independently by Filmakers Inc. and distributed by RKO Radio Pictures. Lupino co-wrote the screenplay with Collier Young, adapting a story by Daniel Mainwaring, and brought with her a sensibility informed by work both in front of and behind the camera. The production employed the RKO stalwart Nicholas Musuraca as cinematographer, which would pay dividends in the film’s stark visual palette that reinforces its identity as a film noir movie.

The film’s roots in reality are plain: it was based on the genuine 1950 killing spree of Billy Cook. Lupino interviewed the two real-life hostages taken by Cook and obtained releases that allowed her to incorporate elements of their ordeal into the script. Of note is how the film’s production navigated the Hays Office and contemporary censorship. Lupino reduced the number of deaths in the on-screen narrative to secure approval—an ethical and practical compromise that nonetheless did not blunt the film’s brutality or tension. The film’s running time is tight—71 minutes—an austerity that contributes to its status as an efficient film noir movie.

As a historical milestone, The Hitch-Hiker was the first mainstream-released American film of its kind directed by a woman. The film’s preservation in the United States National Film Registry in 1998 marks official recognition of its cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance. That designation invites critics and historians to revisit it not only as a piece of crime storytelling but as a moment of breakthrough for women filmmakers in Hollywood—an accomplishment deeply relevant when studying the lineage of the film noir movie.

Plot Overview and Narrative Economy

The Hitch-Hiker tells a bare, brutal story: two friends from El Centro—Roy Collins and Gilbert Bowen—drive south on a fishing trip and pick up a hitchhiker, Emmett Myers. The hitchhiker appears ordinary at first but soon reveals himself as a dangerous fugitive and a killer. He pulls a gun, takes them hostage, and forces them to drive into the Baja California desert as he seeks escape by ferry. What follows is a succession of humiliations, sadistic games, and missed opportunities for escape, all structured as a forward inexorable motion toward capture or death. The film’s narrative economy—71 minutes of concentrated dread—marks it as a potent film noir movie that has little need for subplots or diversion.

The transcript of the film reveals how Lupino leans on small, vivid moments to build dread: a newspaper broadcast, the hum of a car radio, a demanded demonstration of marksmanship where Bowen is forced to shoot a tin can from Collins’ hand. Those scenes operate like a machine: each move serves to underscore Myers’ unpredictability and the hostages’ vulnerability, and each moment tightens the audience’s awareness of how precarious the trio’s dynamic has become. As a film noir movie, the story concentrates on the moral exposure of ordinary men when confronted by extraordinary evil.

Directing and Writing: Ida Lupino’s Control of Tone

Ida Lupino’s directorial approach prioritizes rhythm, economy, and a relentless focus on character psychology. Lupino and Collier Young co-wrote the screenplay, tightening the narrative around a few set pieces that allow the film to function as an intense psychological trip. Lupino’s direction does not aim for spectacle; instead it mines the unease of ordinary spaces—the car’s interior, a roadside store, an abandoned airstrip—for the accumulation of menace. This choice situates The Hitch-Hiker within the formal lineage of a film noir movie that relies upon atmosphere and characterization over flashy set pieces.

Lupino applies a form of restraint that reads as both moral seriousness and technical savvy. She stages each interaction to foreground Myers’ dominance while leaving room for the two hostages’ gestures of decency, fear, and stubborn attempts at resistance. Those choices matter in a film noir movie, because the genre’s ethical texture depends on the collision between personal codes and criminal amorality. Lupino’s camera, often close and unglamorous, emphasizes the small humiliations and the tiny ways in which the hostages’ identities erode under pressure.

Her collaboration with Nicholas Musuraca—whose experience at RKO included dark, expressionistic photography—delivers a visual field that supports Lupino’s intentions. The film’s black-and-white palette, the interplay of daylight desert expanses and nighttime shadows in the car, and the sharp, sometimes off-center framing of faces all cohere to create the film’s signature unease. In practical terms, Lupino’s direction marks the film as a serious contender in the catalog of classic film noir movie efforts from the period.

Performances: William Talman, Edmond O’Brien, and Frank Lovejoy

The Hitch-Hiker’s power inheres as much in the cast as in the screenplay. William Talman’s Emmett Myers is a study in compact menace. Talman invests the role with a casual relish and a cruelty that never becomes theatrical. He speaks in conversational tones even as he exerts life-or-death control, and that tonal normalcy makes him more threatening: he resembles a man one could pass in a grocery store and thereby dramatizes the film noir movie theme of danger lurking in the ordinary.

Edmond O’Brien as Roy Collins provides the film’s moral center. O’Brien plays Collins with world-weary decency—he is a man defined by obligation to family and duty. That makes Collins a sympathetic figure; the audience roots for him because he seems fundamentally aligned with social bonds and responsibility. Frank Lovejoy’s Gilbert Bowen offers a different temperament—more practical, sometimes nervy, more prone to bravado and regret. The interplay among the three actors creates an uneven triangle of power: Myers’ calm menace, Collins’ conscience, and Bowen’s fluctuating nerve. The performances cohere to create a microcosm of the film noir movie’s fascination with how character collapses under pressure.

Cinematography, Editing, and Sound: Minimal Means, Maximum Tension

Nicholas Musuraca’s cinematography is an integral contributor to the film’s claim as a film noir movie. Musuraca’s work is sculptural: he translates Lupino’s sparse direction into images that emphasize texture and shape. Interiors of the car are captured in close quarters; long shots of the desert create a counterpoint of exposed vulnerability. The film’s black-and-white images are used economically to create psychological angles: light and heat press inward from the outside world, while shadows and night consolidate the villain’s control.

The editing, credited to Douglas Stewart, maintains a pace that privileges the scene and the beat. The film does not rush to spectacle; rather it lingers enough on each exchange to allow dread to accrete. The music by Leith Stevens is used with restraint; where present it underscores the film’s tension rather than manipulating every turn. Sound design also plays a key role—the car’s radio, local radio broadcasts, and intercom announcements function as narrative signals, often providing the characters with information that drives action or false security. In that sense, sound is an agent in this film noir movie, shaping choices and outcomes.

The Real-Life Basis: Billy Cook and Ethical Adaptation

Lupino’s film draws from the notorious Billy Cook killing spree, and the film’s production notes indicate Lupino interviewed the two men Cook held hostage. This direct engagement with her source material gave her film a lived-in authenticity. Yet studio and censorship demands required adaptation choices: the number of on-screen deaths was reduced for the Hays Office, and Mainwaring’s original story became the seed for a narrative more interested in psychological exposure than sensational gore. The result preserves the horrors of the original cases while presenting them through a dramatic lens calibrated for maximum tension and moral clarity—traits important to any rigorous analysis of a film noir movie.

There is an ethical austerity to Lupino’s adaptation. The film refuses to glamorize violence; it places the viewer in the position of witnesses to coercion, cruelty, and the slow erosion of human dignity. In doing so, the film acknowledges its real-world origins without turning them into mere spectacle. As a film noir movie, this restraint is significant: it positions the film on the side of moral observation rather than lurid exploitation.

Scene-by-Scene Critical Commentary (Selected Sequences)

1. The Pick-Up and First Reveal

The film’s first sustained jolt comes when Myers reveals his true nature. The car, intended as a mundane vessel for a fishing trip, becomes a capsule of threat. Myers’ instructions—how to sit, where to put hands, which side to exit—are banal and methodical, and that is what makes them so chilling. The transcript captures the nerve of these moments in terse lines:

"I'm Emmett Myers. Do what I tell you, and don't make no fast moves or a lot of dead heroes back there getting nervous." [07:10]

That sentence, delivered without flourish, becomes a declaration of the film’s ethical terrain: everything the villain says is ordinary but lethal in consequence. As a film noir movie, this scene establishes the rules of domination and the hostages’ immediate need to learn them or die. Lupino’s staging emphasizes close quarters, the intimacy of the car, and the small actions—hands on the steering wheel, a glove compartment opened—that will be governed by force. That psychological spatiality (car as tomb) is a classic move in the film noir movie playbook.

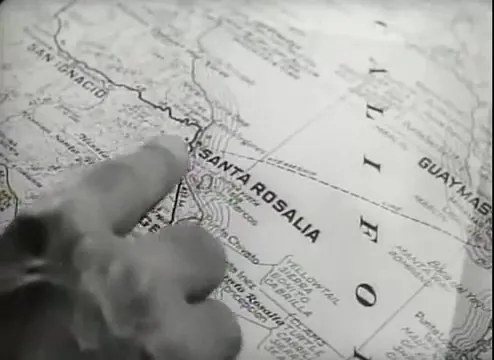

2. The Map and the Route South

Myers’ manipulation extends beyond menace into choreography. He uses a map spread on the car hood to assert control and to share his itinerary to Santa Rosalia—a destination that promises escape. The map scene is a theater of domination: a mundane object becomes the locus where plans and threats are made visible. The transcript puts this plainly:

"Spread the map out on the hood... Look for a town called Santa Rosalia... About five hundred miles." [14:31]

The scenic economy is striking: a map, a few gestures, the cruel implication that these men no longer travel for pleasure. As a film noir movie, the sequence is an exemplary use of a domestic prop to signify existential danger. The desert spaces they cross are as much moral terrain as they are geographical. The map’s lines are thus ominous, pointing toward an inevitable confrontation where the social order reasserts itself.

3. The Tin Can Shooting—Humiliation as a Means of Control

One of the film’s most harrowing set pieces is the scene in which Myers forces Bowen to shoot a tin can from Collins’ hand. The scene’s choreography, dialogue, and tonal inflection all combine to make it a study of sadistic power. The transcript documents this moment’s escalation in a way that emphasizes the play between theatrics and danger.

"Collins, put the can out on that rock there... Take it out on that point there... Hold it closer... Shoot." [15:52–17:12]

The scene works because it transforms a juvenile test of skill into a life-or-death scenario. Lupino’s camera observes without cynicism; in that observation, the spectator becomes complicit in the humiliation. The tin-can episode is instructive to any student of a film noir movie because it demonstrates how villains in the genre weaponize petty rituals in order to dominate men who, until that moment, had ordinary claims to respect and self-determination.

4. Radio as a Narrative Engine

Throughout the film, radio broadcasts perform structural work. They supply the characters (and the audience) with crucial information about the manhunt and the fugitive’s description. Lupino uses radio not as mere background noise but as a narrative engine. The hearings of the news amplify the claustrophobia because the characters learn that police across state lines are on alert. The transcript contains memorable lines where the radio narrator frames Myers as a "hitchhike murderer" and describes the details that could attract or endanger the hostages:

"At the top of the news tonight is the report that the hitchhike murderer, Emmett Myers, is still at large... Myers is slight, twenty eight years of age... His right eyelid is partially paralyzed." [20:04–20:34]

The radio’s repeated interventions create a narrative rhythm that turns the film’s silent miles into a succession of dangerous checkpoints. It is an effective technique in any film noir movie—the intrusion of public information into private terror. Lupino weaponizes broadcasting to generate dramatic irony, where the audience may know more than the characters and thus endure heightened anxiety.

5. The Gas Station and Small Acts of Kindness

The sequence in which Collins and Bowen purchase provisions and are forced to act under Myers’ scrutiny reveals how ordinary kindness becomes both a vulnerability and a strategy. Myers orders them to handle the exchange, isolates the English-speaking men from conversation, and watches how they interact with locals. The tense negotiation at the shop shows how the film noir movie refracts social codes into objects that matter—food, cigarettes, a child’s presence, a watch gifted by a wife.

These details—Bowen’s wedding ring, the watch he claims was a gift, his later confession about stealing a watch in youth—are small, humanizing facts that Lupino uses to create emotional stakes. The men’s identities are not blank; they have histories, families, and small acts of tenderness. That is what the film noir movie does best: it reminds the audience precisely what stands to be lost.

6. The Ruined Crankcase and the Long Hike

A pivotal sequence finds the car disabled, forcing the three to continue on foot. The broken crankcase is an effective mechanical device that converts mobility into vulnerability. For characters trapped by geography, walking becomes exposure. The film stages their physical deterioration and the subsequent escalation, as Myers drives the men to further degradation and the repeated threat of abandonment. The transcript captures the grim exchange:

"What did you do to it?... There's a great big hole in that crankcase... Alright. We'll walk." [50:11–50:21]

Here the film noir movie trope of travel-as-penance is explicit: the journey’s logic shifts from leisure to flight and from travel to trial. Lupino’s camera does not romanticize the desert; it reveals how the environment accelerates fear and reduces the men to choices that measure courage and selfishness.

7. Santa Rosalia: The Ferry and the Final Tension

The film narrows to its final geography in Santa Rosalia. The ferry to Guaymas, the burned ship, and the local fishermen become the last throbbing nodes of possibility. Myers’ attempt to secure passage and his eventual recognition—followed by the local response—provides a denouement that fuses vigilance and fortune. The film positions these events in a way that suggests the collective efficacy of local knowledge against itinerant violence. In this final stretch, The Hitch-Hiker functions as a film noir movie that is oddly civic in its conclusion: the community’s recognition defeats the isolating aggression of the criminal.

Reception, Box Office, and Legacy

Contemporary reviews were mixed, but later reevaluations have celebrated the film’s craftsmanship and impact. The Philadelphia Inquirer praised the picture’s minimalism—three competent actors, rugged scenery—and called Lupino’s direction "masculine strength." The New York Daily News similarly commended her decisive use of the real-life incident. Over time, critics and scholars have come to regard The Hitch-Hiker as one of Lupino’s most compelling achievements and as an influential example within the corpus of mid-century crime cinema. It continues to be cited as an essential film noir movie for students of the genre.

Commercial details are sparse in the historic record; production was independent and the picture opened in March 1953. Its distribution by RKO ensured a general release. Perhaps more important than its box office success is its preservation: in 1998 it was added to the National Film Registry for its cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance. That institutional honor recognizes the film not simply as a gripping crime drama but as an artifact worth preserving—an acknowledgment that has only heightened scholarly and popular interest in the film as a canonical film noir movie.

Why The Hitch-Hiker Endures as a Film Noir Movie

There are several reasons The Hitch-Hiker remains essential to anyone serious about the film noir movie tradition. First, its narrative focus is almost puritanically concentrated: the film refuses to be distracted by extraneous subplots and instead interrogates, with clinical thoroughness, what coercion does to ordinary men. Second, it is a director’s film: Ida Lupino’s vision—her knack for pacing, scene selection, and moral clarity—makes the film more than a sensational retelling; it makes it an interrogation of fear and responsibility. Third, the film’s formal choices—Nicholas Musuraca’s photography, Douglas Stewart’s editing, Leith Stevens’ economical score, and the sound design’s use of radio—work in concert to produce a sustained sense of dread that is characteristic of the best film noir movie efforts.

Finally, the performances anchor the story in an emotional reality. Talman’s chilling casualness, O’Brien’s decency, and Lovejoy’s wry toughness create a triangle of dynamic tension that keeps the viewer invested. These factors together establish The Hitch-Hiker as a minimalist but maximalist film noir movie: small in scope, vast in consequence.

Key Themes and Their Relevance to the Genre

The Hitch-Hiker stages a collection of themes that are central to any study of a film noir movie: vulnerability, masculinity under siege, the banality of evil, and the social mechanisms that respond to crime. The film’s hostility to sentimentality is one of its most distinctive features. Instead of allowing melodrama to humanize the villain, the film insists on a hard, observational stance. In that respect it aligns with film noir movie traditions that foreground a skeptical view of human nature and institutions. Yet Lupino’s film also includes a moral element: it does not cynically endorse nihilism. The community’s role in the capture preserves a notion of collective moral responsibility that complicates the more despairing aspects of film noir movie narratives.

Another important theme is the collapse of trust. Many film noir movie narratives hinge on betrayal: lovers, associates, or systems turning against protagonists. In The Hitch-Hiker the collapse is interpersonal and external. The men’s trust in public life—the assumption that strangers on the road can be hospitable—becomes a fatal risk. The film is therefore an incisive meditation on risk, trust, and the fragile agreements that underwrite social life, all central motifs in a film noir movie analysis.

Technical Notes for Students of Cinema

Students and scholars examining The Hitch-Hiker as a film noir movie should take specific note of the following technical elements:

- Camera placement and framing: Lupino and Musuraca often use tight framing in the car to generate claustrophobia. The camera’s proximity to faces amplifies small gestures and micro-expressions—an economical technique that renders long monologues unnecessary.

- Lighting contrasts: Even in daylight, the film finds shadows—inside the car, under awnings, in alleyways. These contrasts are less expressionistic than some noirs, but they aid the film’s psychological tone.

- Sound as expository tool: Radio bulletins provide key revelations and false leads. Lupino uses these broadcasts both as plot mechanics and as commentary on how public information shapes private fate.

- Performance economy: Talman’s Myers is not melodramatic but quietly theatrical; his restraint makes his actions more terrifying. O’Brien and Lovejoy counterbalance him with everyday gestures that cloak their fear in ordinary masculinity—another classic film noir movie trait.

- Use of location: The desert and small-town Mexico settings convert distance into isolation. Lupino exploits the environment’s emptiness to accentuate helplessness: an essential lesson for those studying the film noir movie’s spatial logic.

Comparative Notes: Where The Hitch-Hiker Fits Among Film Noir Movies

The Hitch-Hiker differs from many classic film noir movies in its minimal cast and its near-linear, forward motion. Where some noirs create labyrinthine moral webs across multiple characters and subplots, Lupino’s film is ascetic: three men on a road, one killer, two hostages. That concentration gives it a surgical precision. Yet in its thematic preoccupations—fatalism, the banality of evil, the collapse of ordinary trust—it remains aligned with the great film noir movie tradition. It is a study in how the noir sensibility can be expressed not only through crime melodrama and urban shadowplay but also through simple, relentless, human cruelty enacted across open spaces.

Another point of comparison is the film’s female authorship. Film noir movie histories have often marginalized women as directors; Lupino’s film disrupts this narrative. Her control of tone, her focus on male vulnerability, and her refusal to sexualize or glamorize violence mark a distinct directorial voice. In that sense, the film stands as an important touchstone for the many ways a film noir movie can be structured and ethically framed by a director who approaches material with moral seriousness rather than exploitative appetite.

Preservation and Cultural Memory

The Hitch-Hiker’s selection for the National Film Registry cites its cultural, historical and aesthetic significance—an institutional recognition that reorients how the film is taught and researched. Preservation ensures the film will remain accessible for generations of film students and viewers who wish to see how minimal means can produce maximal dread. For historians of the film noir movie, this preservation confirms the film’s status not merely as a historical curiosity but as a living document in the broader story of postwar cinema.

Concluding Assessment: A Compact Classic of the Film Noir Movie Tradition

The Hitch-Hiker is a compact, unembellished, morally urgent film. It is minimal in length and maximal in effect. Ida Lupino’s direction, the spare screenplay, the disciplined performances, and the austere technical craft combine to create a film that remains one of the most incisive studies of coercion and courage in mid-century American cinema. As a film noir movie, it embodies the genre’s preoccupations while expanding its formal possibilities: the noir sensibility here thrives in concentrated human interaction rather than sprawling urban melodrama.

For those studying the film noir movie, The Hitch-Hiker offers a clear lesson: terror is not produced by elaborate plots or grandiose spectacle but by the patient, unrelenting enactment of domination upon ordinary lives. Lupino’s film makes that truth visible, and the film’s preservation ensures that future viewers will continue to see how a director’s moral courage can produce a work that instructs and unnerves in equal measure.

In the final analysis, The Hitch-Hiker remains essential viewing for anyone interested in the form and function of the film noir movie. Its economy, its grim moral register, and its formal clarity make it a useful text for classroom discussion, film criticism, and personal reflection. The film endures because it asks urgent questions about ordinary vulnerability and collective response—questions that are central to the film noir movie’s ongoing relevance.

Selected memorable lines that encapsulate the film’s mood:

"Do what I tell you, and don't make no fast moves..." [07:10]

"Spread the map out on the hood... Look for a town called Santa Rosalia..." [14:31]

"Hold it closer... Shoot." [16:52]

"At the top of the news tonight is the report that the hitchhike murderer, Emmett Myers, is still at large..." [20:04]

These lines, spare and direct, show the film’s economy of dialogue and how the film noir movie can be propelled by choice lines that double as thematic signposts.

For Further Viewing and Study

Students and enthusiasts wishing to deepen their understanding of the film noir movie should pair The Hitch-Hiker with other noir entries that emphasize minimalism and moral pressure. Viewing it alongside other Ida Lupino-directed projects and Nicholas Musuraca’s RKO noirs can illuminate continuities in lighting, framing, and ethical attention.

Above all, The Hitch-Hiker rewards multiple viewings: each time the viewer returns, the film’s small choices—exact camera placements, truncated lines, the placement of a prop—reveal additional layers of craft and meaning. For anyone interested in how a film noir movie can be as much a moral inquiry as an entertainment, Lupino’s film remains a model of composure, economy, and nerve.